Passing the Weeks Act

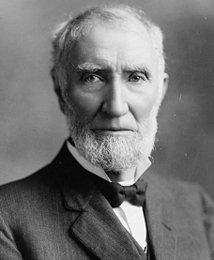

Speaker of the House Joe Cannon.

In the decade following Senator Pritchard’s 1901 bill, Congress rejected more than 40 bills calling for the establishment of eastern national forests. Senators and congressmen opposed these measures for a variety of reasons. Some western representatives (and conservation groups) who supported the national forests in principle resented possibly losing funding to their eastern counterparts. Many fiscal conservatives agreed with House Speaker Joe Cannon when he declared "not one cent for scenery."

Political conservatives noted that the federal government lacked the constitutional authority to purchase private land. Some wanted not only to block the legislation but dismantle the Forest Service entirely and open up the national forests for private development. Others felt that states should look after their own forests. Indeed, some states had already taken action to protect forests. Wisconsin had created a 50,000-acre forest reserve in 1878 to protect the headwaters of major rivers; Pennsylvania made a similar move in the 1890s. In 1885, the New York State legislature established the Adirondack Park from state holdings, declaring the area "forever wild" in its state constitution.

Those who championed private property rights could point to what George Vanderbilt had been doing just outside of Asheville, North Carolina. During the 1890s, as interest in preserving and protecting the southern Appalachians was growing in Asheville, Vanderbilt had quietly purchased 100,000 acres of cut-over woodlands to add to his Biltmore Estate and ordered the estate forester, Carl Schenck, to begin planting trees to restore them. Though the Biltmore Forest would become known as the Cradle of Forestry, ultimately Vanderbilt couldn’t afford to operate both his forest and his mansion and would sell the forest.

After making little headway in Congress, the Appalachian National Park Association and the Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests shifted tactics. To get around the issue of states’ rights, by 1901 the Appalachian National Park Association persuaded five southern states to pass legislation granting their consent to the purchase of land by the federal government. That same year, President William McKinley established the first national forest east of the Rocky Mountains in Oklahoma from land still in the public domain. In 1903, the group began campaigning for a national forest reserve instead of a national park and even changed their name to the Appalachian National Forest Reserve Association to reflect this emphasis.

U.S. House in session, May 1911.

The cause received a boost with the establishment of the U.S. Forest Service in 1905 and the placement of the forest reserves under professional management. President Theodore Roosevelt’s conservation crusade was in full swing, led in part by his Forest Service chief, Gifford Pinchot. Pinchot and other conservationists in the federal government were very concerned about improving and protecting rivers and waterways as well as forests. With Roosevelt’s approval, Pinchot organized several conferences and meetings to focus attention on the need to conserve natural resources.

In 1907, the American Forestry Association joined with local and regional groups and women’s garden clubs to bring national attention to eastern forests. The organization’s monthly magazine began featuring articles documenting the latest studies on flooding and forests and editorials tracing the legislative battles in Washington. Lumber manufacturing associations and magazines supported the forest movement, believing that government intervention was needed to stabilize the volatile lumber market.

Meanwhile, nature provided a case study of the important role forest cover plays in protecting watersheds. In March 1907, heavy rains brought flood waters racing down the Monongahela River in West Virginia and caused some $100 million dollars in damage. The waters surged into the city of Pittsburgh, drowning people, destroying homes, and leaving behind $8 million of damage. The flood hit the same month that congressional opponents of Roosevelt’s conservation agenda managed to overturn the Forest Reserve Act and place the power to create national forests in the hands of the legislative branch.

While conservation organizations worked the halls of Congress, the U.S. Geological Survey had permission from 9 states to determine what land should be purchased and declared national forests. In short order, those states officially granted consent for federal land purchases in the interest of creating public forest reserves. Now what was needed was a federal law authorizing the purchase of private land to protect watersheds.

Congressman John Wingate Weeks.

Leadership on the issue came from a surprise source. Congressman John Weeks, a Republican from Massachusetts, was a former naval officer and a successful banker. Elected to the House in 1905, two years later Weeks was appointed to the House Committee on Agriculture by Speaker Cannon. At first Weeks didn’t understand why. Having few farmers in his district, he had little interest in the agricultural matters that came before Congress. He was concerned, though, about the damage logging had done to the White Mountains. It was near where he had grown up and where he now summered with his family. Speaker Cannon told him that "if you can frame a forestry bill which you, as a business man, are willing to support, I will do what I can to get an opportunity to get its consideration in the House." The man who had once declared "not one cent for scenery" had changed his mind; it was only a matter of time until the bill passed.

In 1908, Weeks introduced a bill proposing that the federal government purchase lands near the headwaters of navigable streams by using receipts from already established forest reserves. The bill went nowhere. The following July, Weeks amended the bill, adding that the purchased lands would be permanently maintained as federal forest reserves as a way to protect the headwaters of navigable waterways, a move that would pass constitutional review under the commerce clause. In December, Senator Jacob Gallinger of New Hampshire introduced an identical bill in the Senate. With Speaker Cannon’s approval (though he personally abstained from voting on the final version), the House passed the bill on June 24, 1910; after some delays, negotiations, and filibustering, the Senate did likewise on February 15, 1911. On March 1, 1911, President William Howard Taft signed the Weeks Act. With the stroke of his pen, the national forests had become truly national. And now the hard work of establishing national forests in the East and protecting and restoring watersheds could begin.

Additional Resources

Chronological List of Actions leading up to passage of the Weeks Act. [PDF]

John Wingate Weeks (1860-1926), a brief biographical portrait.

"Appalachian Forest Bill Dead," from The Southern Lumberman, April 25, 1908: 28. [PDF]

Legislative bill to create Appalachian and White Mountain National Forests ruled unconstitutional by House Judiciary Committee in 1908.

The Weeks Bill, introduced July 23, 1909, in the House of Representatives, 61st Congress, First Session, H.R. 11798. [PDF]

"Record of Votes on the Weeks Bill to Create National Forests," lists the March 1, 1909, voting record from the U.S. House of Representatives on the Weeks Bill, from American Forestry Association Bulletin, 1910. [PDF]

"The Battle for the Weeks Bill," looks at the debates surrounding the proposed bill, from American Forestry, vol. 16 (March 1910):133-144. [PDF]

"The Weeks Bill in Congress," a story of the bill's passage in the House and its failure in the Senate, from American Forestry, vol. 16 (August 1910): 463-480. [PDF]

"The Passage of the Appalachian Bill," a discussion of the bill's passage in the Senate, including the voting record and full text of the final version of the Act, from American Forestry, vol. 17 (March 1911): 164-170. [PDF]

"The Appalachian Forests: Putting the New Law into Operation," looks at the first few weeks of actions following the signing of the Act, from American Forestry, vol. 17 (May 1911): 288-293. [PDF]

"The John Weeks Story," a 1961 USFS pamphlet on John Weeks and his work surrounding the passage of the Weeks Act. [PDF]

"Philip P. Wells in the Forest Service Law Office," from Forest History, vol. 16 (April 1972): 22-29. Article is an excerpt from memoirs of Philip P. Wells, USFS law officer from 1907-1910. Includes discussion of his role in passage of the Weeks Act. [PDF]