Driving for Pleasure: Roads & Scenic Drives in the National Forests

The automobile changed everything about recreation in the national forests. The late nineteenth century saw many innovations and experiments in motor-powered transportation in the US and abroad, and by the early 1900’s cars were becoming a common sight in many cities and towns. As production methods and engineering improved, and the advantages of the horseless carriage became more obvious, automobile ownership grew quickly from 8,000 cars in 1900 to 40 million cars and trucks by 1930.1

Road through Madison Canyon, Gallatin National Forest, Montana, 1930.

A person could get much farther in a car than a carriage, and to move so much faster through the landscape was a novel experience. It was exciting, and people were eager to find new places to go. From a Sunday drive to "auto pioneering," auto tourism swept the nation, propelling millions of Americans into the countryside seeking adventure on the roads. Many headed to the national forests, drawn by their scenic beauty and the respite they provided from the heat and congestion of the cities.

The nation’s roads, however, were not ready. Many had evolved from earlier foot or wagon trails, and still ranged from dirt to dust to mud depending on the weather. Regional and trans-continental "auto trails," such as the Lincoln Highway, the Yellowstone Highway and the Trail to Sunset, developed in the early twentieth century, were rarely paved.2 In 1911 the National Highways Association was launched to promote a nationwide highway network funded and developed by the federal government, as opposed to piecemeal development by state and local entities. The Daughters of the American Revolution soon joined the "better roads movement," advocating for a transcontinental highway that followed historic trials such as the Santa Fe Trail and the Cumberland Road.3

I well remember driving over the old road in October, 1912, from Barstow to Needles, California, and it took me four days of constant struggle, fighting every mile of the way through deep sands, alkali marshes, and talus slopes where the cross washes cut the road into thousands of transverse ditches. I made the same drive last month over the new road, 164 miles, in perfect comfort, taking it easy and without shifting gears once, in eight hours.

-O.K. Parker, Better Roads and Streets, 1915

Commercialization of auto tourism followed closely. The Rand McNally Company was among the first to capitalize on the trend. In 1916 they combined the driver’s need for clear directions with the hoteliers’ need for customers and published the Auto Trail series. These maps and text descriptions of interstate auto routes included listings of subscribing businesses. Rand McNally combined their guides with an aggressive effort to mark entire routes, creating the first numbered marking system for highways. This alleviated the confusion caused by regionally developed roads that would end abruptly or change names at a county or state line.4 An initiative to develop a federally-numbered highway system began in 1925, but it wasn’t until the late 1930’s that the nation had an interstate system of paved roads criss-crossing the country. These included U.S. 1, U.S. 40 and U.S 66.5

The "See America First" advertising campaign during the first half of the twentieth century played on patriotic sentiments, linking national tourism with patriotism. The campaign urged middle-class citizens to spend their vacation dollars in the US instead of Europe, and claimed the vast scenic beauty of the American West surpassed even the Alps.6 Thousands embarked on road trips to see the country, especially its national parks and forests. Yet much of the road building efforts of the Forest Service had been directed toward providing access for logging and communications. These roads were not designed with scenic attributes in mind, let alone safety. As thousands of auto tourists poured into the forests, it soon became clear that better roads were necessary.

Of particular importance for the increase of use [of the national forests] is the systematic and progressive development of roads and trails by which the Forests are being made more generally accessible. Every road and trail, whether it is built primarily for protection or for the development of some material resource, opens up new features of scenic interest.

-Report of the Forester, 1919

The Federal Aid Road Act of 1916 acknowledged the need for better roads in the national forests and provided limited funding for their construction.7 The Federal Aid Highway Act of 1921 stipulated funding for two types; forest highways intended for public travel and local community access, and forest development roads for the protection and utilization of the forests.8

While road construction in national forests continued to be focused on utility, the idea of preserving and highlighting scenic beauty was gaining awareness. Scenic parkways were being developed in many parts of the country, examples being the Bronx River Parkway in Westchester County, NY and the Columbia River Highway in Washington (both 1922), and the Mount Vernon Memorial Parkway in Alexandria, VA (1932).9 The roads were designed to preserve natural beauty and enhance the driving experience with wide medians and side margins and engineered to accentuate scenic views. As the concept of engineering roads for pleasure driving spread, these parkways served as prototypes for subsequent scenic highway projects such as the spectacular Going-to-the-Sun road in Glacier National Park (1933),10 and the Blue Ridge Parkway (construction began in 1935) in the Shenandoah Mountains, which travels through several national forests.

View of Big Branch Creek Valley, off forest road through Green Mountain National Forest, east of Danby, Vermont, 1941.

Mobility increased dramatically after World War II as family incomes increased, automobiles became less expensive, and the federal government embarked on a program to create a nationwide network of "super highways." This combination opened the national forests to even greater numbers of automobile tourists. The 1953 annual report of the chief of the Forest Service noted that, "In addition to the 33,006,885 visits to national forest recreation areas, some 84 million traveled highways and roads through the national forests in order to enjoy the natural forest environment, the scenery, and the climatic relief which the altitude and forest provide."11

In 1964 the President’s Recreation Advisory Council, made up of the secretaries of the Interior, Agriculture, Defense, Commerce, Health, Education, and Welfare, and the Administrator of Housing and Home Finance Agency, wrote a proposal for "A National Program of Scenic Roads and Parkways." Their reasoning as stated:

- because driving for pleasure is one of America's most widely and actively engaged in outdoor recreation pursuits;

- because of the steeply mounting number of families owning automobiles and possessing the leisure time, income and desire to see and otherwise enjoy America's wealth of scenic and natural beauty, both close to home and at far distances;

- because our rapid urban and metropolitan growth is increasing the need for and decreasing the open space resources for outdoor recreation;

- because of the substantial economic benefits generated by tourism and sightseeing made possible by attractive roads and parkways; and

- because of the great potential gains in esthetic and recreation benefits known to be associated with future road planning, design, and construction activities.

While that program was not funded until 1991, the Forest Service established its own Scenic Byways System in 1987. The initial roster of nine picturesque roads quickly grew to 30 within two years, and that number had grown to 138 designated roads by 2010.12

Family viewing the mountains east of Spruce Knob, Monongahela National Forest, West Virginia, 1966.

The first comprehensive study of outdoor recreation, undertaken by the Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Council in 1960, listed driving for pleasure as the number one outdoor recreational activity. In a follow-up study twenty years later it was still listed in the top ten outdoor activities. In a 2007 study, while not in the top ten, driving for pleasure still showed growth as an outdoor activity.13

America’s ongoing love affair with the automobile ensures that auto tourism will continue to be a force in recreational planning in the National Forests. The 2010 National Visitors Use Monitoring summary report by the Forest Service reported an estimated 300 million visits by vehicle on Forest Service roads or nearby corridors to view scenery.14 Such facts speak to Americans’ continuing desire to explore their country, their history, and their natural wonders by the means that is the most accessible as well as intimate, an automobile. To further explore the history of auto tourism in the national forests and in America, see the resources listed below. Additional resources may be found using the Forest History Society research databases.

Written by: Nancy C. Nye, special projects, Forest History Society.

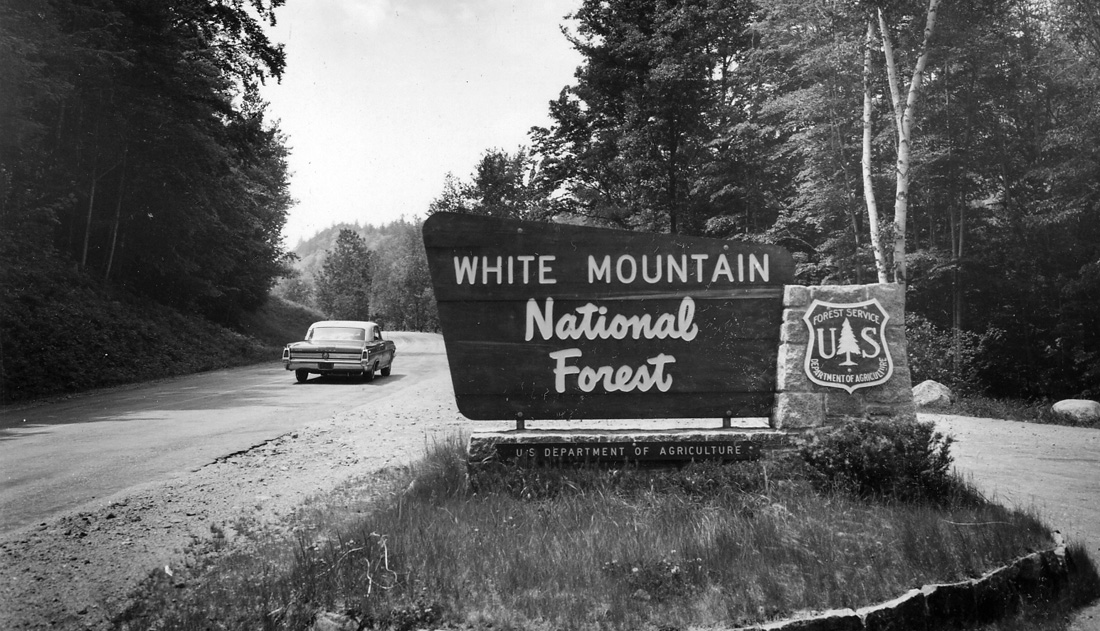

Forest entrance sign on the Kancamagus Highway, west of Conway, New Hampshire, 1965.

Driving for Pleasure - Resources

Bruce, Robert. The National Road: The Most Historic Thoroughfare in the United States. Brooklyn, NY: Brooklyn Eagle Press, 1916.

This early touring guide to the National Old Trail Road includes detailed maps, descriptions and historical information, and photographs.

Automobile Club of Southern California. The National Old Trail Road to California, Part 1. Los Angeles: Automobile Club of Southern California, 1916.

Original guidebook to the “all year route” from Los Angeles to New York.

Rand McNally’s Auto Trail Map - District 4, 1918.

Lowe, J. M. National Old Trails Road, the Great Historic Highway of America. Kansas City, MO: 1925.

History of the original trails incorporated into National Old Trails Road, as well as the political process of developing the National Old Trails Road, by Judge J. M. Lowe, one of the foremost proponents of a federally funded transcontinental highway.

Frothingham, Robert. Trails Through the Golden West. New York: Robert M. McBride & Co., 1932.

Auto tour guide to historical and natural sites through Arizona and California.

Meinecke, E. P. "The Trailer Menace." US Department of Agriculture, internal memo, 1935.

Forest Service. National-Forest Vacations. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture, 1940.

Forest Service. National Forest Recreation Ways: A Development Opportunity. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture, 1963. [PDF]

Recreation Advisory Council. National Program of Scenic Roads and Parkways. Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1964. [PDF]

Federal Highway Administration. America’s Highways, 1776-1976: A History of the Federal Aid Program. Washington, DC: US Department of Transportation, 1976.

Provides a general history of the US interstate highway system.

Forest Service. Tour US: National Forest Scenic Byways. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture [no date]. [PDF]

Havlick, David G. "Behind the Wheel: A Look Back at Public Land Roads." Forest History Today (Spring 2002): 10-20. [PDF]

Additional Links

America’s Byways

Website for federally funded scenic roads program.

American Auto Trails

Website for current information about historic auto trails, as well as publications. Sponsored by Caddo Publications.

National Forest Scenic Byways

Website with links to over 130 scenic drives through National Forest lands.

Rails and Trails.com

Website about transportation history, particularly in Ohio. Includes examples of early Rand McNally maps and route guides for various highways systems.

Save the Auto Camp

Website devoted to the history of auto camping and efforts to identify and preserve original auto camps, focused on the Northwest.

Highway History

This umbrella site includes articles on many aspects of the development of the American highway system. Sponsored by the Federal Highway Administration, and administered and mainly authored by Richard F. Weingroff, an information liaison specialist with FHWA’s Office of Infrastructure. Of particular relevance are:

- Weingroff, Richard F. "Along the Interstates: Seeing the Roadside." Highway History. US Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration. [Retrieved Feb. 7, 2012]

- "Goods Roads Everywhere: Charles Henry Davis and the National Highways Association." Highway History. US Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration. [Retrieved Feb. 7, 2012]

- "History of Scenic Roads." Highway History. US Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration. [Retrieved Feb. 7, 2012]

- Map of the Transcontinental Trails of the USA, 1923. Shows named auto roads at that time, no numbered highways existed yet. [Retrieved March 14, 2012]

- Weingroff, Richard F. "The National Old Trails Road." Highway History. US Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration. History of the development of national roads, auto trails, auto tourism and the national movement that pushed it forward. [Retrieved Jan. 11, 2012]

- Mertz, Lee. "Origins of the Interstate." Highway History. US Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration. [Retrieved Jan. 11, 2012]

Notes

1 Havlick, David G. No Place Distant: Roads and Motorized Recreation on America’s Public Lands (Washington, DC: Island Press, 2002) 15.

2 There are many fascinating sources of information related to old auto trails. They are mentioned in Havlick and discussed in detail in Weingroff, Richard F., "National Old Trails Road: Part 1 and Part 2."

3 Weingroff, Richard F. Good Roads Everywhere: Charles Henry Davis and the National Highways Association, and Weingroff, National Old Trails Road Part 2: The Bourne Report. [Retrieved February 8, 2012]

4 Akerman, James R. "Selling Maps, Selling Highways: Rand McNally’s Blazed Trails Program." Imago Mundi 45 (1993): 77-89.

5 Weingroff, Richard F., "Along the Interstates: Seeing the Roadside," US Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration website, Highway History. [Retrieved February 7, 2012]

6 Shaffer, Maguerite S., See America First: Tourism and National Identity, 1880-1940 (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2001). The importance of this campaign in drawing Americans onto the roads and to National parks and forests is also mentioned in Havlick.

7 Richard F. Weingroff, "Federal Aid Road Act of 1916: Building the Foundation," Highway History. [Retrieved February 14, 2012].

8 Forest Service, Report of the Forester (Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, 1922) 41.

9 Richard F. Weingroff, "History of Scenic Roads Program," Scenic Byways '88: A National Conference to Map the Future of America's Scenic Roads and Highways (Washington, DC: US Dept. of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration, 1988).

10 National Park Service, "Going-to-the-Sun Road: An Engineering Feat," Historic American Engineering Record (Washington, DC: US Department of the Interior, 1990).

11 Forest Service, Annual Statistical Supplements to Chiefs’ Reports, Forest Service, U. S. Department of Agriculture 1938-1953 (Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, 1953) 8.

12 US Department of Agriculture, Office of Information New Release "Forest Service Designates Nine Scenic Byways," and National Highway Administration, America’s Byways website. [Retrieved October 10, 2011]

13 H. Ken Cordell. "The Latest Trends in Nature-based Outdoor Recreation." Forest History Today (Spring, 2008): 5. [PDF]

14 Forest Service, National Visitor Use Monitoring Results, USDA Forest Service, National Summary Report: Data collected FY 2005 to FY 2009. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, 2010. [Retrieved March 14, 2012] [PDF]