Protection and Restoration

Planting tree by hand on Shawnee National Forest, 1938.

The Weeks Act of 1911 authorized the federal government to purchase private lands for stream-flow protection and to maintain the acquired lands as national forests. Its passage made possible the creation of the eastern national forests. Section 2 of the law made provisions for fighting forest fires with the cooperation of the states. The Weeks Act set aside $200,000 in matching funds to be distributed to states with forest protection agencies. Those forestry agencies could then apply for up to $10,000 to be used for fire patrolmen salaries, provided the state would match the amount. Cooperation with the Forest Service’s State and Private Forestry branch on fire problems later evolved into efforts on insect control and forest diseases. The funding also encouraged several states to establish or expand state forests.

Though Section 2 would later prove to have been visionary, buying land and creating national forests was the act’s main purpose. The Forest Service recommended lands for purchase while the Geological Survey evaluated the acreage to be sure the reserved lands would maintain navigable waterways. The law authorized a National Forest Reservation Commission to consider and approve the land purchases. The commission was composed of the secretaries of War, the Interior, and Agriculture, and two members each from the House and Senate. (One of the first senators first appointed was Jacob Gallinger, who had sponsored the Senate’s version of the bill.)

Working on behalf of the commission, purchase agents would select an area, organize it into a purchase unit, and then submit the unit to the commission for approval. If approved, the land would be appraised and an offer issued. The government would only buy from a willing seller at a fair-market price. If purchase units were approved but not enough land could be purchased, the purchase unit would be "abandoned." Because not all the land in a purchase unit could be purchased for one reason or another, there is private land within a national forest boundary. In fact, about half the land on a typical eastern national forest is private land. Today the federal government purchases land in order to "block up" an area and create contiguous federal land, which makes it easier to manage.

Crew of men en route to fire, Pisgah National Forest, North Carolina, 1923.

In a few cases, like the Pisgah purchase unit, a single purchase unit was large enough to become a national forest. Usually, though, several purchase units were assembled into a national forest. For ease of administration, multiple national forests were sometimes later consolidated into one national forest. A good example of this was the Boone National Forest in North Carolina. Created from the Boone and Mt. Mitchell purchase units in January 1920, it was added to the Pisgah fourteen months later and ceased to exist as the Boone.

The commission held its first meeting on March 7, 1911. Twenty days later, Forest Service chief Henry Graves submitted recommendations for the "Purchase of Land under the Weeks Law in the Southern Appalachian and White Mountains," They totaled 13 areas in 9 eastern states, though only 11 of them were eventually purchased. (The Youghiogheny area in western Maryland and the Smoky Mountains in Tennessee and North Carolina were eventually "abandoned." The latter became a national park in 1939.) The first purchase made under the Weeks Act was in McDowell County, North Carolina, for 18,500 acres. The 10 tracts of land cost $100,000, or $5.41 an acre. The McDowell purchase was later incorporated into the Pisgah National Forest.

The Pisgah was the first national forest established in any eastern state from lands acquired under the Weeks Act. President Woodrow Wilson established it on October 17, 1916. Part of the Pisgah’s original lands included the forest that George Vanderbilt once owned. His widow, Edith Vanderbilt, sold 86,700 acres for $433,500, or $5 per acre, to the government to establish a national forest. To ensure her husband’s conservation legacy, she accepted $200,000 less than the government had offered.

What was the condition of the land being purchased in the East? According to the commission’s report in 1915, the condition of the 1.3 million acres approved for purchase by then was as follows: 51 percent were "culled and cut-over lands," with most of the valuable trees already cut; 28 percent were "virgin timberlands" (what is today often called "old growth"); 11 percent were reserved by the sellers for logging to be done, though cutting would be regulated by the government; 2 percent was abandoned farmland, some of which was reverting to forest; and 8 percent was considered "barren or covered by a nonmerchantable growth of timber," or timber in places that weren’t easily accessible to loggers. Those percentages would change over time; the percentage of abandoned farmland would skyrocket in the 1930s as farmers fled their worn-out agricultural lands.

CCC planting crew on national forest land in Michigan, July 1936.

During its first 21 years, the commission approved the purchase of 42 areas, totaling 4,727,680 acres. Purchasing land became easier after passage of the Clarke-McNary Act in 1924, which allowed the protection of entire watersheds. It also contained a provision "for the production of timber" as a reason for purchasing land. States used the increase in funding to further develop their own forests and parks. The funding also fostered closer cooperation between federal, state, and private landowners. The Woodruff-McNary Act of 1928 raised the annual appropriations to $8 million. These two laws made possible the purchase of national forest land in the rest of the country, eventually bringing hundreds of thousands of acres in the western United States into the National Forest System via the Weeks Act.

Fire truck loaded and ready to respond to a call, White Mountain National Forest, 1931.

In the second half of the 1920s, purchases slowed and the commission focused on adding land to existing national forests rather than creating new forests. Land acquisition took off again in 1933 during President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. From 1933 to 1942, his administration purchased 14.1 million acres in 20 states, much of it exhausted farmland scattered from Texas to Wisconsin, for rehabilitation and restoration. Through programs like the Civilian Conservation Corps, Penny Pines, and the Dixie Crusaders, billions of trees were planted and the number of forest fires reduced on the eastern forests. In addition, the Corps built campgrounds and other recreational facilities and constructed hiking trails, which encouraged visits to the eastern national forests and laid the foundation for the postwar recreation "boom."

Land purchases slowed down during World War II but resumed afterward. Over the next several decades, the amount of land purchased waxed and waned, peaking in 1947 at 371,671 acres approved for purchase, dipping to under 6,000 in 1960 and then rising in 1966 to nearly 169,000 acres. From 1966 to 1970, more than 600,000 acres were approved for purchase. Additional funding came from the Land and Water Conservation Fund Act of 1965, which went towards purchasing land “primarily of value for outdoor recreation purposes,” but done under authority of the Weeks Act. In 1976, the responsibilities the National Forest Reservation Commission were transferred to the secretary of Agriculture. In all, gross acreage totaled 20,782,632 acres approved for purchase, and cost $118,054,248, or $5.68 per acre.

Additional Resources

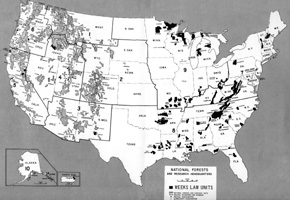

Weeks Law Purchase Units Maps

A series of maps depicting the expansion of Weeks Act forest purchase units over time.

Weeks Law Forest Creation

A chronological list of national forests created from Weeks Act lands.

Weeks Law Purchase Units

A chronological list of the Weeks Act purchase units created from 1911 to 1932.

U.S. Forest Service. "Final Report of the National Forest Reservation Commission, 1976." [PDF]

Provides detailed data on lands purchased under the Weeks Act from 1911 through 1976.

Gross Acreage Approved for Purchase Under Weeks Law by Fiscal Year, 1912-1976. [PDF]

A table featuring the total acreage and average price for each year of the National Forest Reservation Commission.

National Forest Reservation Commission Members, 1911-1966. [PDF]

A chronological listing of all seven members of the Commission.

"Purchases Made Under Weeks Law," from The Southern Lumberman, December 16, 1911: 27. [PDF]

Approval by the National Forest Reservation Commission of the first purchases of land (in McDowell County, NC) under the Weeks Law.

Paxton, Percy J. "National Forests and Purchase Units of Region Eight," July 1, 1950. [PDF]

Compiled by a longtime member of the Forest Service Lands staff.

Townsend, W.B. "The Appalachian National Forest," from The Southern Lumberman, December 23, 1911: 83. [PDF]

An article by the President of the Hardwood Manufacturers' Association, on the conservation of the Appalachian forests.

"Pisgah Forest Purchased," from American Forestry, vol. 20 (June 1914): 425-429. [PDF]

Discusses the purchase of lands from Edith Vanderbilt for Pisgah National Forest in North Carolina.

Graves, Henry S. "The New National Forests of the East," from The Southern Lumberman, December 18, 1915: 98-99. [PDF]

Chief Forester Henry S. Graves looks at what has been accomplished under the Weeks Law during the first four years of its existence.

Ayres, Philip. "Our Eastern National Forests: Record Steady Progress in Acquisition Under the Provisions of the Weeks Law." [PDF]

Looks at lands purchased during the first 19 years of the Weeks Act, from American Forests and Forest Life, vol. 36 (July 1930): 438-9, 483.

"Cooperative Forest Fire Control: A History of its Origin and Development Under the Weeks and Clarke-McNary Acts," a 1964 USFS publication. [PDF]

This excerpt (pp. 1-27) details the history of the Weeks Act and its impact on early fire policy.