“The Lands Nobody Wanted”

The Weeks Act and the creation of the eastern national forests can trace its intellectual roots back more than a century before the act was signed into law in 1911. Concern about the impact of logging and clearing of land for agriculture initially emerged in the American Revolution era. In the 1830s, the Hudson River school of landscape painters and Transcendentalist writers began romanticizing the vanishing wilderness and lamenting its destruction; their words and images seeped into the American consciousness over the next half century and continue to influence our perceptions of nature to this day.

Cut and burned over pine lands in Chippewa County, Michigan.

In 1864, Vermont native George Perkins Marsh published his highly influential book, Man and Nature: Or, Physical Geography as Modified by Human Action. The combination of history and science with personal observation at home and abroad found in Man and Nature provided the intellectual foundation for the forest preservation movement that soon followed. His study of ancient Mediterranean civilizations argued that the wanton destruction of forests had led to their downfall. He implied it would be the fate of America if government action was not taken to manage its vital watersheds. Though Marsh’s work inspired efforts to preserve what remained of American public lands and to protect eastern forests from further destruction, it would be a dozen years before those first steps were taken.

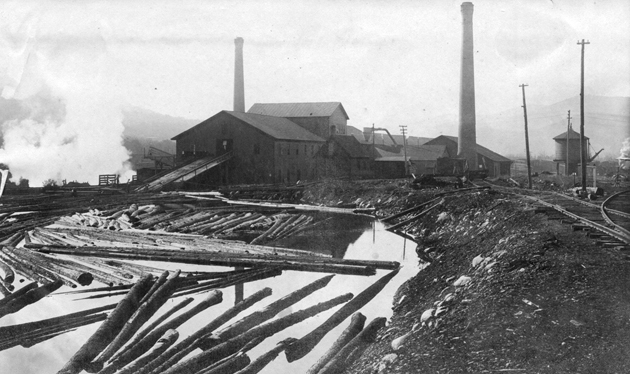

Sawmill in North Woodstock, New Hampshire, circa 1903.

In 1876, Congress approved funding for a study on American forest conditions and the appointment of a federal forest agent to do the work. Franklin Hough compiled information on forest resources, the lumber industry, and relevant land laws into three reports. Hough recommended the withdrawal of public lands containing forests "from sale or grant" and the establishment of a permanent bureau to study and manage those forests. The Department of Agriculture responded by establishing the Division of Forestry in 1881 to continue studying forest conditions. A quarter-century later the division would become the U.S. Forest Service.

Hough called the destruction of young timber needed to supply future generations "the highest degree of folly" and expressed his fear that, given the rate at which timber was being cut, Americans would run out of wood within a few decades. Census bureau statistics fed the fear of a "timber famine." Between 1850 and 1900, lumber production rose from 5.4 billion board feet to 44.5 billion board feet. Hough and his successors Nathaniel Egleston and Bernhard Fernow worked with groups like the American Forestry Association, the Boone and Crockett Club, and the Appalachian Mountain Club, in pressing Congress to address the crisis.

The first step came with the Forest Reserve Act of 1891. The law gave the president the power to set aside public land as forest reserves to protect watersheds (in 1907 they would be renamed "national forests"). In the East, however, where little federal public land remained, watersheds remained unprotected. By the 1880s loggers had removed most of the valuable timber from New England and the Great Lakes region, and were buying forests in the Pacific Northwest and the South. Eastern farmers who had exhausted their lands and had moved west also left behind land prone to fire and erosion. The abandoned farms and badly cut-over forests became known, in the words of forest policy analysts William Shands and Robert Healy from their eponymous book, as "the lands nobody wanted."

Slash remaining from cut-over land on mountainside, New Hampshire, circa 1910s.

Popular vacation spots in New Hampshire’s White Mountains and the Southern Appalachians happened to be near some of the areas affected by bad logging practices. Upset by what they saw, concerned citizens established regionally-focused organizations like the Appalachian National Park Association (founded 1899) in North Carolina and the Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests (founded 1901). Both groups immediately started petitioning the federal government to buy land in both areas and protect it as a national park. In 1900, Congress gave $5,000 to Secretary of Agriculture James Wilson to "investigate the forest condition in the Southern Appalachian Mountain Region of western North Carolina and adjacent states."

Issued in 1901, Secretary Wilson’s report ran more than 180 pages. The U.S. Geological Survey provided the latest data on the geology, geography, and climate of the Southern Appalachian region and its river basins. The report emphasized the region’s economic importance to the entire nation. It included photos showing flood-damaged areas and burned-over lands to illustrate the damage done by indiscriminate logging and agricultural clearing. In his conclusion, the secretary did not mince words, declaring, "The regulation of the flow of these rivers can be accomplished only by the conservation of the forests...Federal action is obviously necessary."

Instead of creating a national park, though, he recommended the establishment of a national forest preserve. President William McKinley favored the measure and asked Congress to approve the proposal. On January 10, 1901, North Carolina Senator Jeter Pritchard introduced a bill authorizing $5 million for establishing the Southern Appalachian Forest Reserve. Ten more years, however, would go by before Congress would send a bill to the White House for signature.

Additional Resources

Conrad, David E. The Land We Cared For...A History of the Forest Service's Eastern Region. USFS, 1997.

This excerpt looks at the history and legacy of the Weeks Act.

Shands, William E. "The Lands Nobody Wanted: The Legacy of the Eastern National Forests," a chapter from Origins of the National Forests: A Centennial Symposium. Steen, Harold K., ed. Durham, NC: Forest History Society, 1992.

Looks at the history of the creation of the eastern national forests, and their importance to the nation [PDF version].

Shands, William E. and Robert G. Healy. The Lands Nobody Wanted: A Conservation Foundation Report. Washington, DC: The Conservation Foundation, 1977.

A comprehensive report on the fifty national forests east of the Rocky Mountains.

"The Beginnings of the National Forests in the South: Protection of Watersheds." [PDF]

An original essay by Gerald W. Williams, a former national historian of the U.S. Forest Service.