Trail Building in the National Forests

Early Trails in the Forests

The Forest Service began building trails in the 1890s, when the national forests were first set aside as forest reserves. Those trails were not scenic walks, but designed as the quickest way between two points and built primarily for communication and fire fighting activities. Random trails created by the consistent use of visitors to access scenic areas were not of much concern to the early Forest Service.

"Mere ways through the forest, whether marked or not, are not regarded as trails; they are matters of woodcraft rather than of permanent forest improvement. A trail is a narrow highway over which a pack animal can travel with safety during the usual period when the need for a highway exists."1

A 1915 Forest Service publication, Trail Construction on the National Forests, discerns the two types of trails

Foresters and packhorses ready to hit the trail, Okanogan National Forest, Washington, 1909.

In the days before telephones and radio, Forest Service trails were the means of communication between remote stations. Travel and communication was done primarily by horseback, and packhorses were used to deliver supplies to distant lookout towers. Especially during fire season, efficient trails were essential to move men and equipment quickly. The value of the road and trail system to the Forest Service was recorded in each yearly Report of the Chief, the annual report of the Forest Service. Included were the amount of road and trail mileage constructed that year, the total miles of roads and trails, and the distribution by state of the budget appropriation for roads and trails.

Many large areas are still entirely without even the simplest trail facilities. Valuable forests which will be urgently needed in the future are being jeopardized by reason of the fact that they are without adequate roads or trails by which fire-fighting supplies and men may be brought in case of need.

Report of the Forester, 1922

During World War II, the national forest road and trail system was considered a national security asset. Access to the timber was critical for the war effort as it provided material for many war-related necessities, including shipping containers, cots, and airplane propellers.2 One Forest Service document, assessing the potential value of the national forests road and trail system for the military, stated: "It can furnish a supplementary transportation system in the mountain regions, especially in the West, which is largely screened from the air and therefore not as liable to bombing as the open trunk highways."3

Trails for Recreation

The first edition of Trail Construction on the National Forest (1915) defined trails as transportation routes for pack animals and classified them according to their forest management use: as main trails, secondary trails, and branch trails.4 In the second edition (1922), the categories were more specific and included the "Purpose of Trails: (a) Fire control; (b) administrations: (c) grazing: (d) recreation."5

"Recreation trails will ordinarily be constructed only where the need is made clearly apparent by public demand or by existing heavy use of trails over which travel is very laborious or difficult."6

Clearly the recreational use of trails was beginning to be a consideration in trail planning, although to a limited extent.

CCC crew at work on trail to top of Notch Mountain, Grand Mesa National Forest, Colorado, 1933.

Based on the Forest Service annual reports, it was not until the mid-1930s that trails were considered purely in terms of recreational value, particularly for their scenic attributes. The Report of the Forester, 1933, is the first annual report to include hiking as an activity in the report on recreational use. It is included in a group labeled "motorists, horsemen, hikers, etc."7

The following year saw extensive infrastructure improvement and construction by the Civilian Conservation Corps and other work relief programs of the Depression era, which would continue into the early 1940s. Among the many construction efforts undertaken were trails designed specifically for hiking.

"In trail construction (recreational trails) it should be the idea to make them as inconspicuous as possible. In this way their effectiveness should be increased, and the pleasure obtained from walking over such a trail should be of the highest quality. Ordinarily speaking, trails should go from one point of interest to another as directly as it is reasonable in keeping with the conformation of the ground."8

A 1934 plan described the aesthetic goal.

CCC enrollees at work building the Glen Ellis Falls Trail in New Hampshire, 1938.

A National Trail System

During the era of relative prosperity of the 1950s and 1960s, the popularity of hiking continued to grow. Demand for all aspects of outdoor recreation was surpassing the available resources for national as well as state and local governments. In 1958 Congress formed a special commission, the Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission (ORRRC), to take a comprehensive look at current recreational resources as well as future needs. The commission spent three years gathering data and studying trends, working with local and state governments to survey existing recreation resources.

America must not neglect its heritage of the outdoors--for that heritage offers physical, spiritual, and educational benefits, which not only provide a better environment but help to achieve other national goals by adding to the health of the nation.

Outdoor Recreation for America: Report to the President and to Congress by the Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission, 1962

Hikers on the Black Angel Trail, White Mountain National Forest, New Hampshire, 1958.

Their 1962 report discussed the benefits of outdoor recreation for increasing the health and wellbeing of American citizens, and reiterated the importance of including recreational use in management policies at all governmental levels. This report paved the way for such significant legislation as the Wilderness Act (1964) and the National Wild and Scenic Rivers Act (1968), which set aside large sections of undeveloped land to ensure there would be wild places for future generations to enjoy.9

In direct response to the findings of the ORRRC, President Johnson gave a speech on February 8, 1965.10 In it he called for a national system of trails, as well as a national wild rivers system and for full funding of the Land and Water Conservation Fund. A national trail study was begun and the resulting report, Trails for America, was published in 1966.

"In order to provide for the ever-increasing outdoor recreation needs of an expanding population and in order to promote public access to, travel within, and enjoyment and appreciation of the open-air, outdoor areas of the Nation, trails should be established (i) primarily, near the urban areas of the Nation, and (ii) secondarily, within established scenic areas more remotely located"11

Congress passed the National Trails System Act in 1968 with this intent.

This act of Congress established four major trail systems, national recreation trails, national scenic trails, national historic trails, and connecting or side trails. The Appalachian Trail and the Pacific Crest Trail were designated as the first national scenic trails. Management of the national trail system trails falls to the agency with administrative responsibility for the majority of land on which the trails lay, usually with the National Forest Service or the National Park Service.12

In 1978 Congress passed an amendment to the original act that created 4 national historic trails and added the Continental Divide Trail as a national scenic trail.13 By 2014 the national trail system included 30 national scenic or historic trails, and over 1,100 national recreation trails.14

The forgotten outdoorsmen of today are those who like to walk, hike, ride horseback, or bicycle. For them we must have trails as well as highways. Nor should motor vehicles be permitted to tyrannize the more leisurely human traffic.

President Lyndon B. Johnson, Natural Beauty Message, February 8, 1965

Increasing Demand for Trails, 1970s

During the 1970s, recreational use of national forest trails reached new levels of popularity. By 1976, the Forest Service was spending $5.7 million on trail maintenance and more than $3 million for trail construction each year. A trail assessment underway in the 1970s suggested that approximately 50 percent of all trail miles were not in adequate condition. The Forest Service's 1977 statistics showed more than 10.5 million visitor-days on a 97,000-mile trail system (a visitor-day equaled one visitor for a 12-hour period). With the increasing popularity of its trails, the agency was also finding increasing numbers of user conflicts - between backpackers and horsepackers, for example, or motorcyclists and hikers - as well as needs for more trail maintenance, visitor education, and improved trail design.

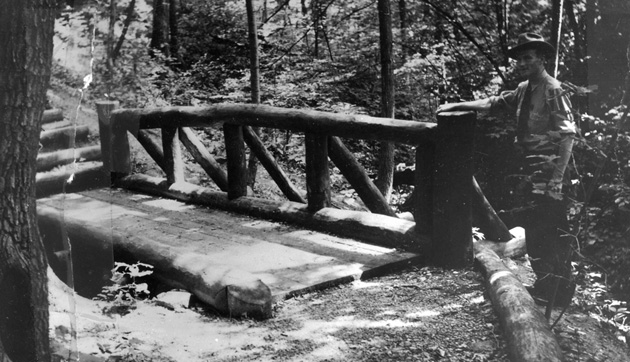

Footbridge at Tinker's Cave Recreation Area, Wayne National Forest, Ohio, 1937.

Forest Service chief John McGuire pointed to many of these issues in a 1977 speech: "When most National Forest trails were built, utility and speed were the prime considerations - not esthetic appeal or quality of the recreational experience. Often, trails were located along canyon bottoms to take advantage of flatter ground and easier construction. Many are snowbound early and late in the season, susceptible to erosion, and costly to maintain. They also provide little opportunity for scenic vistas, and sometimes lie in the paths of avalanches."

The United States has only about 100,000 miles of trails--less than one yard of trail per citizen. Give thanks that not everyone hikes and that hikers do not hit the trail at the same time. If they did, they could all hold hands.

"The Neglected Hiker," Backpacker Magazine, 1976

McGuire proceeded to emphasize that public demands on trails could cause problems. "Nor were these trails designed for all-comers. They were generally meant for occasional use by experienced people and pack and saddle animals. Motorized vehicle use was not anticipated. Nor was safety a great concern. Nor was the sheer volume of use that we see today. . ."

Trails for the Future?

Surveys of recreational users conducted over several decades show that interest in hiking has continued to grow in the 21st century, albeit at a slower rate than the last decades of the 20th century.15 Providing trails to meet the increase in demand, as well as maintain them, has long challenged the Forest Service. Advocates for outdoor recreation have been critical of Forest Service management of its trail resources, although most blame lack of congressional funding more than management policies.16

Accelerated Public Works (APW) workers constructing nature trail, Mark Twain National Forest, Missouri, 1963.

Concerns about the condition of existing trails and the large backlog of maintenance in the late 1980s prompted the Congressional Subcommittee on National Parks and Public Lands, Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, to request the General Accounting Office (GAO) to review the issue of deferred maintenance on Forest Service trails. The committee chair felt that deferred trail maintenance was resulting in the loss of valuable recreational opportunities to the American public, as well as a financial loss of capital investment.

The GAO report found inadequate fiscal funding from 1981-1987 led to the large backlog of deferred maintenance, as well as unfulfilled new trail construction projects. The Forest Service reported that in 1988 the backlog totaled $195 million. Service personnel indicated funding had been inadequate for the previous decade, and budget limitations had led to a sharp decline in skilled trail personnel. The report continued that Congress had increased funding from 19.7 million in 1987 to over $36 million in 1988 and 1989, which allowed for many maintenance and reconstruction issues to be addressed, but would not provide for construction of new trails.17

In 1991 hearings were held by the Congressional Subcommittee on National Parks and Public Lands on the management of America’s recreational trails. A statement presented to the subcommittee by the associate deputy chief of the National Forest System highlights the agency’s dependency on public-private partnerships to expand and maintain recreational trails under their jurisdiction.18 The partnerships included volunteers, hiking clubs, and local governments and businesses.

According to a 2013 conducted by the U.S. General Accounting Office in response to a Congressional request, the total mileage of national forest trails used for recreation and management in 2012 was 158,000. For that year the agency performed maintenance on 37 percent of trails, while only 26 percent met the Forest Service standards for condition. For 2012 the allocated resources were $81.9 million, while the estimated amount required to fully address trail maintenance needs totaled $523.7 million.19

According to Forest Service reports, the allocation for trails generally goes to basic maintenance of existing trails rather than upgrades or new trail construction. Volunteers and outside partners remain an essential means of maintaining and expanding existing facilities, and the advocacy work of out-door clubs and environmental groups, as well as local citizens and businesses, continue as important force in calling for more funding for trail construction and maintenance. Because of recurring budget constraints the Forest Service has continued to rely on the help of volunteers and outside partners for maintenance and enhancements to the national trail system.20

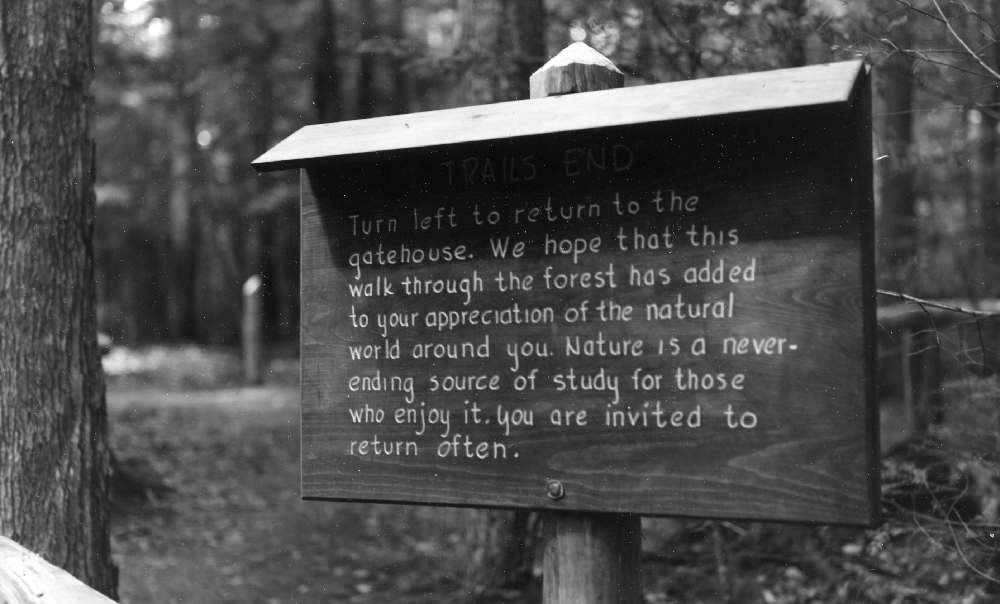

Trails End sign at Dolly Copp Forest Forest Nature Trail, 1962.

Additional information on hiking and trail building in the national forests can be found using the Forest History Society Research Portal as well as additional webpages on recreation in the national forests, hiking, backpacking, the national trail system, and the long trails.

Written by: Nancy C. Nye, special projects, Forest History Society.

Additional Resources

- Daigle, John J., Alan E. Watson and Glenn E Haas. National Forest Trail Users: Planning for Recreational Opportunities. Research Paper NE-685. Radnor, PA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northeastern Forest Experiment Station, 1994. [PDF]

- Lucas, Robert C. and Robert P. Rinehart. "The Neglected Hiker" Backpacker Magazine 4 (1976): 35-39. [PDF]

- Roth, Denis M. The Wilderness Movement and the National Forests: 1964-1980. [Washington, D.C.]: U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Forest Service, 1984.

- Roth, Denis M. The Wilderness Movement and the National Forests: 1980-1984. [Washington, D.C.]: U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Forest Service, 1988.

- U.S. Forest Service. Trail Construction on the National Forests. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1915.

- U.S. Forest Service. Trail Construction on the National Forests. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, 1923. [PDF]

- U.S. Forest Service. Forest Trail Handbook. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, July 1935.

- U.S. Forest Service. Backpacking in the National Forest Wilderness...A Family Adventure. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, 1969.

Notes

1 US Forest Service. Trail Construction on the National Forests. (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, 1915), 8.

2 Manuscript, "The Timber Production War Project," Forest Service History Collection, Forest History Society [no date, no author].

3 Manuscript, "Forest Roads and Trails: Aerial Surveys," Forest Service History Collection, Forest History Society [no date, no author].

4 US Forest Service. Trail Construction on the National Forests. (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, 1915), 8.

5 US Forest Service. Trail Construction on the National Forests. (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, 1922), 5.

6 US Forest Service. Trail Construction on the National Forests. (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, 1922), 6.

7 US Forest Service. Report of the Chief of the Forest Service. (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, 1933), 28.

8 Maughan, Kenneth. "Recreational Development in the National Forests : A Study of the Present Recreational Use and a Suggested Plan for Future Development Together with a Recreational Management Plan for the Wasatch National Forest, Utah," Bulletin of the New York State College of Forestry at Syracuse University VII (May 1934): 97-98.

9 Olson, Brent A. "Paper Trails: The Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission and the rationalization of recreational resources," Geoforum 41 (2010): 447.

10 Johnson, Lyndon B. "Special Message to the Congress on Conservation and Restoration of Natural Beauty," speech, February 8, 1965, accessed October 24, 2014.

11 Public Law 90-543, 90th Congress, S 827, October 2, 1968, "To establish a national trail system, and other purposes."

13 Public Law 95-625, 95th Congress, November 5, 1978, "National Parks and Recreation Act of 1978," accessed October 30, 2014. [PDF]

14 "National Trail System Facts and History," American Trails, accessed October 24, 2014.

15 Cordell, H. Ken. Outdoor Recreation Trends and Futures: A technical document supporting the Forest Service 2010 RPA Assessment, Southern Research Station, USDA Forest Service (2012), 33-35.

16 "National Forest Trails," Wilderness Society, accessed October 22, 2014; and Rob Burbank, "Trails in Trouble," Appalachian Mountain Club, accessed October 22, 2014.

17 Parks and Recreation: Maintenance and reconstruction backlog on national forest trails. Report to the Chairman, Subcommittee on National Parks and Public Lands, Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, House of Representatives, United States General Accounting Office, 1989, accessed June 23, 2015.

18 Henson, Larry. "Concerning Recreational Trails in America, October 31, 1991, Statement of Larry Henson Associate Deputy Chief, National Forest System, Forest Service, United States Department of Agriculture, before the Subcommittee on Energy and the Environment; Subcommittee on National Parks and Public Lands; Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs; United States House of Representatives," 1991, Forest Service Collection files, Forest History Society.

19 "Report to Requestors: Forest Service Trails," U.S. Government Accounting Office, June 2013, accessed October 24, 2014. [PDF]