Hiking in America

Historical Context

At the turn of the 20th century hiking for pleasure was a relatively new concept. America was largely rural until the mid-1800s, and most people lived near open fields and forests. Walking and nature were a part of daily life. With increasing industrialization during the 19th century, however, a walk in the woods would become a luxury for many people, and it wasn’t until the end of that century that hiking was recognized as a recreational activity.

Hiking to a weekend at a Forest Service camp shelter on the Eagle Creek Trail, Mt. Hood National Forest, Oregon, 1919.

Steam engine technology brought industrialization to the northeast region of the United States in the early 1800s, where waterpower was abundant. Mills and factories offered people from isolated rural communities jobs and exposure to new ideas and fashions. As technology evolved, more factories were built across the country, often in larger towns and cities and nationwide, and people migrated from small agricultural communities to new industrial centers on a huge scale.

The housing and commercial districts necessary to support the growing populations expanded into the surrounding countryside, making it more difficult to access open land for recreation. People’s lives in these new industrial centers were structured by work and social activities. The increasingly urban lifestyle of many Americans no longer incorporated rural walking as part of everyday life, both by necessity and choice. A recreational walk in nature required time, effort, and often money, amenities enjoyed by the wealthy but dear to the average person.

... a specimen of God's handiwork that shall be to them, inexpensively, what a month or two in the White Mountains, or the Adirondacks is...to those easier circumstances.

Frederick Law Olmsted, writing about his plans for Central Park

Vital Open Space

After the Civil War the population of the nation’s cities increased dramatically. Between 1870 and 1900 nearly twelve million immigrants entered the United States.1 Seeking jobs and inexpensive housing, many of these new Americans headed to cities. The rural migration to cities continued as well, causing urban populations to explode. Already limited and inadequate housing soon devolved into overcrowded, unsanitary tenements and slums where human waste, industrial waste and animal waste from horses and slaughterhouses drained onto the streets, running through open gutters which regularly overflowed.

The dire social and health problems that developed in the cities in the latter half of the 19th century inspired movements in social and health reforms, enlightened by new understandings of contagious disease, germ theory, sanitation, and city planning. Many of these issues were highlighted by the devastating effects of the unsanitary conditions experienced in hospitals and prisons during the Civil War, when more soldiers died from disease and wound care than by actual fighting. Reformers realized proper sanitation was essential to public health, and fresh air, sunshine, and open space was considered vital to sanitation planning.

One response to the basic need for clean air and green space was the creation of large public parks. Central Park in New York City was the first in America when planning for it began in 1851. Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux conceived of the park as a naturalistic landscape that included secluded wooded areas as well as rocky outcroppings and open meadows to provide natural settings and ample space for walking, riding, and recreating for all city residents. The emphasis was on "all," as one of the designers’ specific intents was to provide a healthy environment accessible to all citizens, regardless of social or economic status.2

Once opened, Central Park did indeed attract the entire spectrum of New York City’s residents, and provided a unique environment where all social and economic strata of the city mixed freely. Fresh air and space for play and exercise was available to everyone. As a result of the success of Central Park, the urban park movement spread across the U.S. to cities large and small, providing millions of people access to natural areas and open space.

Hiking: America’s New Pastime

Although it was not until 1933 that the Forest Service’s annual Report of the Chief included hiking in its recreational usage reports (reported as "motorists, horsemen, hikers, etc."), its development as a recreational activity can be seen earlier in other aspects of American life, such as outing clubs and outdoor based programs for young people.3

Already there are many walking clubs in America; their memberships are greatest, as might be expected, in New England and on the Pacific Coast. Some of these organizations are concerned chiefly with feats of mountaineering; others with the needs of the greater number of ordinary people.

Going Afoot; A Book on Walking, League of Walkers, 1920

In addition to an increasing awareness of the importance of health and social conditions in the late 19th century, America also experienced an increased appreciation of nature, which continued throughout the 20th century. The pioneer era had long been over and wilderness, which had once seemed in overabundance, began to disappear. This was due in large part to the aggressive tactics of large-scale timber and mining companies, as well as the growth of the railroads which could easily transport those materials to market. Concern began to grow that one of the nation’s iconic attributes, its endless and awe-inspiring wildness, could disappear.

Family hiking in Austin Pass, Mt. Baker National Forest, Washington, July 1925.

While the parks movement offered everyone an experience with nature, wealthy Americans began to seek a more intimate experience with wilderness, but without the masses to share it. Searching for new ways to enjoy nature, some well-to-do Americans joined outing clubs. These organizations became popular in America after the Civil War, their founding inspired by similar organizations in Europe. They were formed primarily as social clubs to promote outdoor activities, and were most popular in larger cities.4

One of the first was the Alpine Club, founded in Williamstown, Massachusetts in 1863, which focused its activities in the mountains of New Hampshire. Other early clubs were the White Mountain Club (Portland, Maine, 1873), the Rocky Mountain Club (Denver, 1873),5 and the Fresh Air Club (New York City, 1890).6 The Appalachian Mountain Club (Boston, 1876), the Sierra Club (San Francisco, 1892), and the Mazamas of Portland, Oregon (1894) remain active outing clubs today, as well as strong proponents of wilderness preservation.

Responding to an advertisemnt run in the Morning Oregonian June 12, 1894: "To Mountain Climbers and Lovers of Nature...It has been decided to meet on the summit of Mt. Hood on the 19th of next month..." More than 300 people encamped on the flanks of Mt. Hood on July 18th. By 8:00am the next day, the first climbing party reached the 11,239' summit, followed by the rest of the 193 men and women who were to reach the summit that day. One hundred and five climbers became charter members.

"(A very brief) History," Mazamas website

Outing clubs organized and promoted hiking trips to nearby areas and developed "pedestrian resources," such as cleared and marked trails, trail maps, and shelters for resting or overnights.

Group of hikers on Mt. Washington, New Hampshire, August 1926.

The Appalachian Mountain Club first published their Guide to Paths and Camps in the White Mountains and Adjacent Regions in 1907. The White Mountain National Forest was established in 1918 and included much of the area explored, mapped, and described by the AMC. The collective trail-building efforts of the early outing clubs provided a significant basis for our nation’s vast network of hiking trails still in use today, as many of the popular hiking areas in the 1880s were eventually to become national forests or national parks.7

Building Up the Young People

The enthusiasm for outdoor-based programs for young people in the U.S. is also evidence for the growing popularity of hiking in the early 1900s. The Woodcraft League was the first to be established in 1902. Founder Ernest Thompson Seton believed the best antidote to the problems of juvenile delinquency in the early 20th century was to teach boys the skills, lore, and law of the American Indians, whom he admired for their spiritual character and intimate knowledge of nature. The League was based on "tribes" and their manual, The Birch Bark Roll, specified clothing and costumes, rituals, and activities.8 By 1910 there was an estimated 200,000 boys enrolled in the Woodcraft League tribes, including special "Indian Scout" tribes organized in impoverished inner city areas. Their activities included camping outs in teepees, growing vegetables and maintaining bird colonies, all on the roof-tops of apartment buildings in the city.9

Remember that the value of the hike is in doing things which you cannot do at home...Make sure that as you travel to the point you have selected that your eyes and ears are open to see the hundreds of interesting things that may be seen along the roadside.

-The Woodcraft Manual for Boys, 1917

The success of the Woodcraft League gained the attention of an Englishman, Sir Robert Baden-Power. Baden-Powell was developing his own program for boys based on his experience training reconnaissance soldiers in the Boer War, and he enthusiastically combined Seton’s woodcraft ideals with his own curriculum and launched the Boy Scouts in 1906 in Britain. Following great success overseas, the Boy Scouts of America was founded in 1910, quickly subsuming other programs for boys, including the Woodcraft League.10 11

Young hikers from the Los Angeles Municipal Camp, Angeles National Forest, California, 1916.

Following the success of the Boy Scouts, several similar organizations for girls were founded. Seton was involved in the promotion of the "Camp Fire Girls," founded by his friends Luther and Charlotte Gulick, in 1911. Based primarily on the Woodcraft League principles with the goal "to guide young people on their journey to self-discovery," Camp Fire Girls quickly grew in popularity and continues as an active organization today.

Julia Gordon Lowe founded the Girl Scouts of America in 1912 after spending time with the Baden-Powers and learning of Mrs. Baden-Power’s Girl Guides in Britain. Lowe returned to Savannah, Georgia, determined to bring Girl Guides to America, where it was quickly embraced, welcomed by girls eager for the same adventures and challenges their brothers found in the Boy Scouts.12

The Girl Scouts believe heartily in woodcraft, in walking and hiking and all kinds of creative camping and allied activities...It puts the 'outing in scouting,' gives us an understanding of our pioneer heritage and leads on to satisfying and adventurous life-long recreations. 'One must begin with the landscape if one is to end with the soul.'

-When You Hike, Girl Scouts of USA, 1930

The strong societal belief in the regenerative power of nature, as well as in the benefits of moral education and physical exercise, led to the wide spread acceptance of these youth-focused organizations during the early 20th century. In all of them, the experiences of hiking, camping, and outdoor activities helped instill an appreciation of nature and outdoor recreation in generations of Americans.

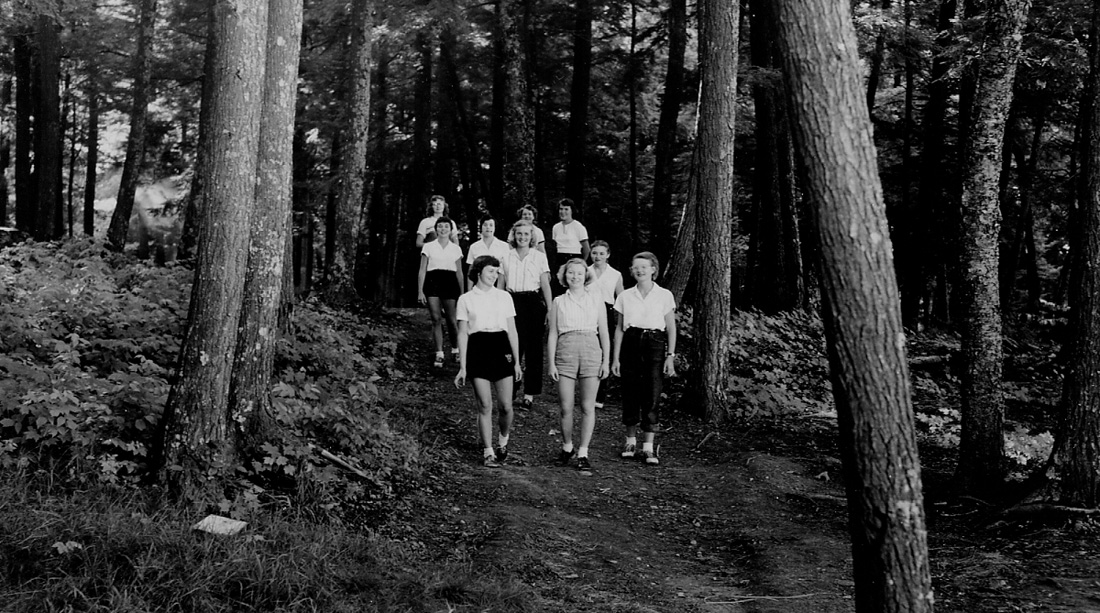

Green Bay Girl Scouts and counselors on woodland trail at Lost Lake Organization Camp, Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forest, Wisconsin, August 1952.

Postwar Leisure Time

As opposed to walking, hiking connotes an intention: a plan, a path, and an experience to be had on the way. One definition of hiking, "walking for pleasure and exercise,"13 suggests that for hiking to become popular, participants must have both the leisure time for pleasure and a desire to exercise. It wasn’t until the 20th century that a significant number of ordinary Americans possessed both at the same time.

The increased leisure of the American people, the growth of automobile and other travel and of interest in outdoor things, the changes in modes of life which accentuate the need and demand for greater recreational facilities all then to enlarge the social and economic importance of the national forests as national public playgrounds and treasure houses of scenic, wild life and other natural values.

-Report of the Chief, 1931

Prior to World War I, the typical American worker expected to work 6 days a week, with Sundays reserved for church and family. Labor reforms after war brought the 5-day work week to many people for the first time. Companies began to offer paid holidays and vacation time as a benefit in order to attract good employees. In addition, innovations in technology after World War II led to the mechanization of many jobs, and work became less labor intensive and more sedentary.14

In the years following World War II, hiking gained popularity as an outdoor leisure-time activity because it was affordable and easily accessible. No special equipment was required and most families owned a car by this time, giving them access to miles and miles of hiking trails in national forests, and national and state parks.

Hikers on rock outcrop above Little Rock Pond, Green Mountain National Forest, Vermont, August 1962.

National forests located near urban areas were accessible to the most people, and subsequently became the most over-used. The Angeles National Forest outside Los Angeles, the old Oregon National Forest near Portland, Oregon, and the White Mountain National Forest near Boston and other New England cities suffered this fate.15 Highway construction began on a large scale in the 1950s, making access easier to more distant national forest trails. The Forest Service was under pressure to keep up with the public’s demand for more and better trails.

The 1946 Report of the Chief states: "Six million visits, adding up to 10,000,000 man-days, were tallied on other national-forest areas for such purposes as hunting, fishing, riding, hiking, nature study and photography, and other hobbies."16 In 1948 the Chief’s report states: "Thousands of miles of hiking and horseback trails are sign-posted and maintained," indicating that trail maintenance and trail improvement was a recognized need by that time.17

Demand Continues to Grow

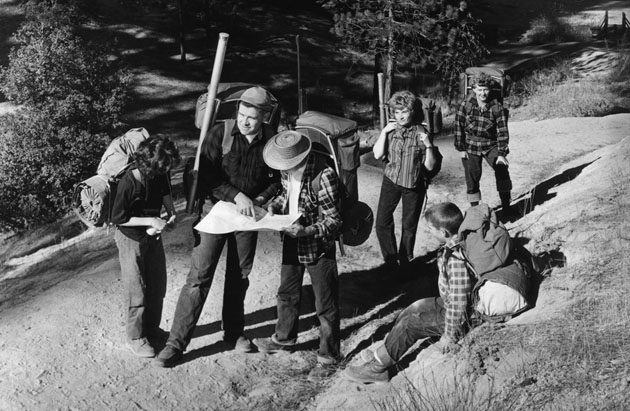

The Rupe family prepares to begin hike, Angeles National Forest, California, December 1962.

The 1950’s saw a recreation boom in the national forests. According to the 1955 Report of the Chief, "Recreation use of the national forests increased from 27 million visits in 1950 to almost 46 million in 1955, an increase which is greater percentage-wise and in actual numbers than the population increase in the United States during the same period. Use has outgrown the facilities available." The report included a table showing the number of hiking and riding related visits to national forests had increased from over 634,000 in 1950 to over 1 million in 1955.18 That number tripled by 1964.19

It is expected that average personal income (after taxes) will rise from the 1953 level of $1,567 to $2,062 in 1975. On the basis of present indications, it is also generally believed that the average work-week and the average work-year will become shorter in the next several years; in other words, employed persons will have more nonwork days available in a given year.

-U.S. Forest Service, Operation Outdoors (1957)

The popularity of hiking continued to increase throughout the rest of the 20th century. Based on data from the National Survey on Recreation and the Environment (NSRE), 69 million Americans went hiking in 1999-2000, representing a 44 percent increase in participation since 1982. Data from the 2008 NSRE showed an increase in hiking of over one million participants in eight years. A 2012 review of national trends, based on subsequent NSRE surveys, showed that participation rates for hiking continued to grow in the first decade of the 21st century, but at a lower rate than during the previous century.20

Hiking remains one of the nation’s most popular outdoor activities, and America’s national forests provide abundant opportunities. As society continues to become more technologically focused, sedentary and urbanized, the value we place on the nation’s vast national forests increases as well. For many, a walk in the woods is still the best cure for the stresses of modern life.

Hiking in the national forests can be explored further using the Forest History Society’s Research Portal. Related topics covered in other webpages here are: Backpacking - a step further; Trail building in the national forests; national recreation trails; and the long trails.

Timeline of Government Programs Related to Hiking, Trail Management, and Outdoor Recreation

1933 – Hiking included for the first time in the Recreational Usage Report of the Report of the Chief, the annual report of the Forest Service published since 1891 (reported as "motorists, horsemen, hikers, etc.").

1945 – Peak of trail mileage in national forests, although the majority of trails were used by the Forest Service for maintenance, logging and communications.

1952 – Report of the Chief recognized the lack of adequate trails.

1958 – Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission (ORRRC) established to create an inventory of outdoor recreational resources.

1962 – Release of Outdoor Recreation for America : A Report to the President and to the Congress by the Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission, Laurance S. Rockefeller, Chairman, 1962: "It shall be the national policy, through the conservation and wise use of resources, to preserve, develop, and make accessible to all American people such quantity and quality of outdoor recreation as will be necessary and desirable for individual enjoyment and to assure the physical, cultural, and spiritual benefits of outdoor recreation."

1963 – Bureau of Outdoor Recreation established by President Kennedy as direct result of findings of ORRRC report.

1965 – Land and Water Conservation Fund [PDF] established by Congress, which designated a portion of receipts from off-shore gas and oil leases be set aside for the protection of national recreational lands, as well as local and state conservation projects.

1966 – Bureau of Outdoor Recreation conducted the Nationwide Trails Study in cooperation with Federal land management agencies, States, and private interests. Their report to President Johnson, Trails for America: Report of the Nationwide Trail Study, recommended the establishment of a national trail system.

1968 – National Trails System Act (P.L. 90-543) [PDF] passed by Congress to meet the demand for recreational trails.

1974 – Congress passed the Renewable Resources Planning Act [PDF], requiring the Secretary of Agriculture to assess the supply and demand situation for the nation’s forests and rangelands, including recreation resources. This resulted in the first national-scale survey of recreation demand, the National Recreation Demand Assessment, which was introduced in 1975.

1987 - President's Commission on Americans Outdoors formed. In July 1988 the task force released their report, Outdoor Recreation in a Nation of Communities. A change in political power in Congress resulted in the report being mostly ignored, although recommendations for state and local governments to expand their outdoor recreation resources were acted upon, particularly in the development of greenways and trails close to metropolitan areas.

1989 - Parks and Recreation : Maintenance and reconstruction backlog on national forest trails. Report to the Chairman, Subcommittee on National Parks and Public Lands, Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, House of Representatives / United States General Accounting Office, 1989.

2008 - Outdoor Resources Review Group was formed as a bipartisan, privately sponsored effort to undertake an assessment of priorities, challenges, and opportunities in outdoor resources. The resulting report, Great Outdoors America [PDF], was released in 2009, which called for a more sustainable approach to recreation resource planning and increased funding for the Land and Water Conservation Fund, established by Congress in 1965. Subsequently, Resources for the Future, a non-profit research organization that was commissioned by the Outdoor Resources Review Group to provide background research and analysis for their work, released a report looking at historical and future trends in recreation use and funding, The State of the Great Outdoors (2009).

2013 - General Accounting Office released their report as requested by the Congressional subcommittee on Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies: Forest Service Trails: Long- and Short-term Improvements Could Reduce Maintenance Backlog and Enhance System Sustainability [PDF]. This report closely examined the extent to which the Forest Service is able to maintain its trail system;, the resources it uses to accomplish that end; complicating factors that affect its ability to maintain the system; and options that could improve current outcomes.

Written by: Nancy C. Nye, special projects, Forest History Society.

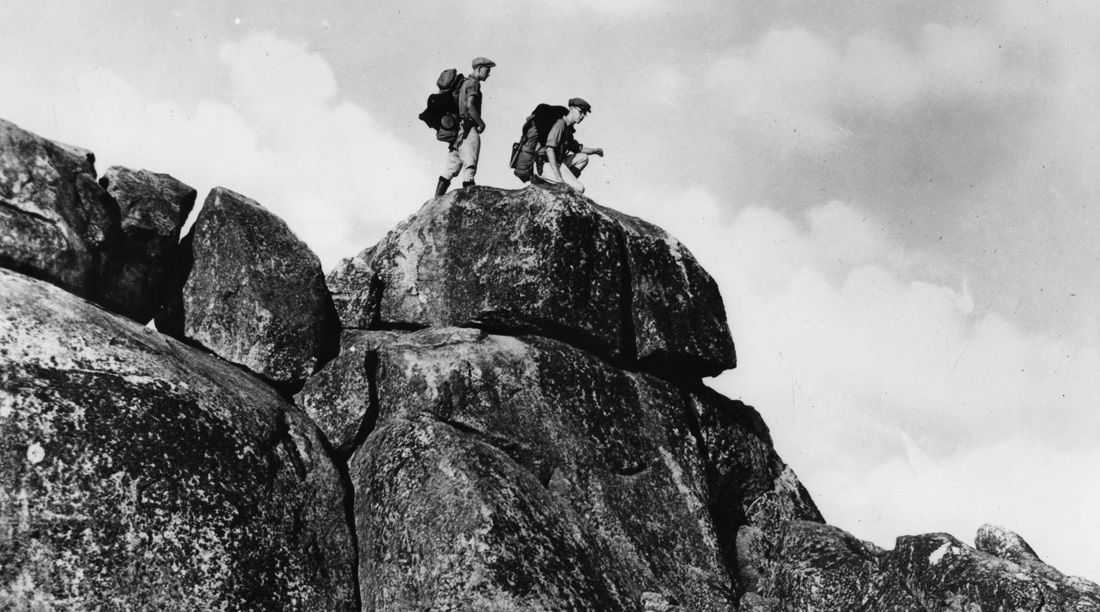

Above the clouds on sharp top mountain peaks along the Appalachian Trail in Jefferson National Forest, Virginia, 1925.

Hiking in America - Resources

- Appalachian Mountain Club, Boston Chapter. Guide to Paths in the White Mountains and Adjacent Regions. Boston: Appalachian Mountain Club, 1920.

An early trail guide to developed trails in the White Mountain area. - Boy Scouts of America. The Official Handbook for Boys. New York: Doubleday, Page & Co., 1913.

- Bureau of Outdoor Recreation. Federal Focal Point in Outdoor Recreation. Washington DC: US Government Printing Office, 1966.

Brochure describing the then new National Trail System. - Bureau of Outdoor Recreation. Trails for America: Report on the Nationwide Trail Study. Washington DC: Department of the Interior, 1966. [PDF]

Pamphlet about new trails from the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation, Department of the Interior. - Bureau of Outdoor Recreation. National Scenic and Recreation Trails. Washington DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1968. [PDF]

- Cave, Edward. The Boy Scout’s Hike Book. New York: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1920.

Written to provide more detailed information than what is included in the official Scout handbook. Includes topics such as different walking gaits, grub lists, and winter hiking. - Christy, Bayard H. Going Afoot: A Book on Walking. New York: Published for the League of Walkers by Association Press, 1920.

Includes a chapter on different hiking clubs across the country as well as specific information on choosing shoes, planning a hike, goal setting. - Daigle, John D., Alan E. Watson, Glenn E. Haas. National Forest Trail Users: Planning for Recreation Opportunities. Radnor, PA: USDA Forest Service, Northeastern Forest Experiment Station, 1994. [PDF]

- Girl Scouts, Inc. Tramping and Trailing with the Girl Scouts. New York: Girl Scouts Inc., 1927; rev. 1930.

- Girl Scouts, Inc. When You Hike. New York: Girl Scouts Inc., 1930.

- Grinnell, George Bird and Eugene L. Swan. Harper’s Camping and Scouting: An Outdoor Guide for American Boys. New York: Harper & brothers, 1911.

- Siehl, George H. The Policy Path to the Great Outdoors: A History of the Outdoor Recreation Review Commissions. Washington DC: Resources for the Future, 2008. [PDF]

- U.S. Congress. National Trails System Act, 1968. [PDF]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture. "Nationwide System of Trails Recommended to Interior and Agricultural Secretaries." Washington, DC, 1967. [PDF]

Press release announcing release of the report "Trails for America" by the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation which called for the creation of national scenic and recreation trails. - U.S. Forest Service. Backpacking in the National Forest Wilderness: A Family Adventure. Washington DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, 1969.

- U.S. Forest Service. Forest Trail Handbook. Washington DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, July 1935.

- U.S. Forest Service. "Woodsy Owl on Hiking and Backpacking" Washington DC: Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, 1976.

- Woolf, Dwight H. Tramping and Camping. By the "Walking Woolfs." Kansas City, KS: S. I. Meseraull & Son, Printers (c.1912).

Describes a walking journey of over 10,000 miles undertaken by a couple to recover the husband’s health. - For more historic photos of hiking on national forests, search the Forest History Society Image Database. Also browse sample images in the Hiking and Riding online gallery.

Links to Additional Hiking and Trail Information

- America’s Great Outdoors – information about the 2010 presidential initiative to "develop a 21st Century conservation and recreation agenda" and increase public access to outdoor recreational opportunities.

- American Hiking Society

- American Trails - includes lists of trails, trail building information, advocacy for trial building and maintenance within state and federal government.

- National Historic Trails - hosted by American Trails

- National Recreation Trails - hosted by American Trails

- National Recreation Trails Database

- National Trails System Map

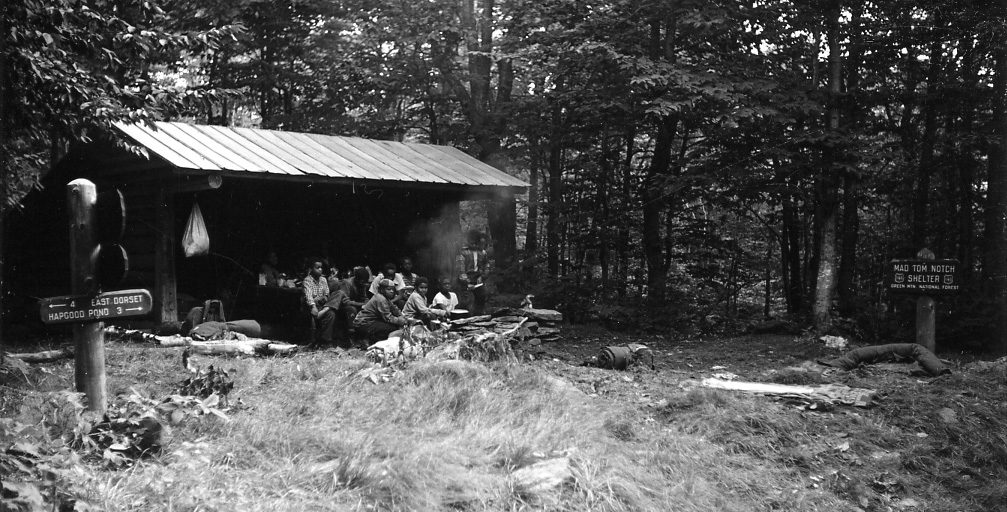

Young hikers from East Harlem Protestant Parish at Mad Tom Notch Shelter, Green Mountain National Forest, Vermont, October 1951.

American Hiking Clubs 1870-1927

- Appalachian Mountain Club, Boston, MA; founded 1876

- The Fresh Air Club, New York City; founded in 1890

- Founded by Henry Ernest (Harry) Buermeyer II and his longtime friend William Buckingham Curtis, who also founded the NY Athletic Club in 1868.

- Sierra Club, San Francisco; founded in 1892

- Mazamas Hiking Club, Portland OR; founded 1894

- Green Mountain Club, Waterbury Center, VT; founded 1910

- California Alpine Club, Mill Valley, CA; founded 1913

- Trails club of Oregon, Portland, OR; founded 1915

- Tramp and Trail Club, Utica, NY; founded 1921

- Potomac Appalachian Trail Club, Washington, DC; founded 1927

Notes

1 "Rise of Industrial America: 1876-1900," Library of Congress, accessed April 7, 2014.

2 Frederick Law Olmsted; Charles E. Beveridge and David Schuyler, eds. Creating Central Park: 1857-1861, The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted; v. 3 Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983).

3 Frederick Law Olmsted; Charles E. Beveridge and David Schuyler, eds. Creating Central Park: 1857-1861, The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted; v. 3 Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983).

4 Charles E. Fay, "The Appalachian Mountain Club," Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 35 (March 1910): 393-400.

6 "Swam for the Presidency: Fresh-Air Club Members have a Novel Annual Election." New York Times, August 1, 1893, accessed March 21, 2014.

7 "Bureau of Outdoor Recreation. Trails for America : Report on the Nationwide Trail Study. (Washington DC: Department of the Interior, 1965), 20. Accessed May 15, 2015. [PDF]

8 Ernest Thompson Seton. The Woodcraft Manual for Boys. (New York: Woodcraft League of America, 1917).

9 Anderson, H. Allen. The Chief: Ernest Thompson Seton and the Changing West. (College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press, 1986), 148-149.

11 "Boys Scouts of America: 100 Years in Review, 1910-2010," accessed March 20, 2013.

12 "Girl Scouts of America: Juliette Gordon Lowe Biography," accessed April 1, 2015.

13 Free Dictionary, accessed February 13, 2013; Oxford Dictionary defines 'Hike' as "long walk, especially in the country or wilderness."

14 Cross, Gary. Social History of Leisure since 1600. (State College, PA: Venture Publishing, Inc., 1990), 163-167.

15 Tweed, William C. History of Outdoor Recreation Development in National Forests 1891-1942. (Washington: US Forest Service, 1989), 3.

16 U.S. Forest Service. Report of the Chief: 1947. (Washington, DC: US Dept. of Agriculture, 1947), 30.

17 U.S. Forest Service. Report of the Chief: 1948. (Washington, DC: US Dept. of Agriculture, 1948), 12.

18 U.S. Forest Service. Report of the Chief: 1955. (Washington, DC: US Dept. of Agriculture, 1955), 5.

19 Clawson, Marion and Carlton S. Van Doren. Statistics on Outdoor Recreation. (Washington DC: Resources for the Future, Inc. 1984), 197.

20 Cordell, H. Ken. Outdoor Recreation Trends and Futures: A Technical Document Supporting the Forest Service 2010 RPA Assessment. (Southern Research Station, USDA Forest Service, 2012), 33-35.