Kieckhefer Container Company

Tweet SharePaperboard, either corrugated or solid, also known as cardboard, fiberboard, or containerboard, has been an essential part of our everyday lives in one form or another for more than a century. It became ubiquitous through the efforts and innovations of fiberboard industry pioneers like the Kieckhefer Container Company. In the first half of the 20th century, Kieckhefer became one of the leading manufacturers in the container industry, known for their shipping containers, paperboard, and milk cartons. This digital exhibit uses material from the Kieckhefer-Eddy files within the Weyerhaeuser Company Records and other sources to tell the stories of the Kieckhefer Company, the Kieckhefer family, and this important segment of the packaging industry.

CONTENTS

Beginnings: 1880–1915

The 1920s: Expansion and Acquisition

The 1930s and 1940s: Boxes Go To War

The 1950s: Milk Cartons and a Merger

Legacy

Resources

Beginnings:

1880–1915

Since arriving in the United States just before the Civil War, the Kieckhefer family has been nothing if not industrious. Charles “Carl” Kieckhefer was born in Prussia (Germany) in 1814 and moved to Milwaukee, Wisconsin, around 1848, where he started a family with his wife, Justine (née Buckholz). Carl was said to wear many hats; various sources report him as being a retail merchant, carpenter, contractor and builder, dealer in horses, and the president of the Union Cemetery. He was also the father of two daughters and four sons. Ferdinand, August, William, and Charles Jr. would follow him into the business world.

Ferdinand started as a clerk at the John Pritzlaff hardware firm, and then began a retail hardware store in 1872. In 1880, with his brother William he formed F. Kieckhefer & Brothers, which later incorporated as Kieckhefer Brothers Company. The company came to own the Milwaukee Stamping Works, which produced tin, enameled ware, shelf hardware, house furnishing, and stoves and ranges. August organized the A. Kieckhefer Elevator Company in 1883 while Charles Jr. became a successful building contractor. Eventually, Ferdinand would buy out his brother’s and others’ shares in Kieckhefer Bros. and merge the business with five other tin-ware and enameled-ware manufacturers to form the National Enameling and Stamping Company in 1899.

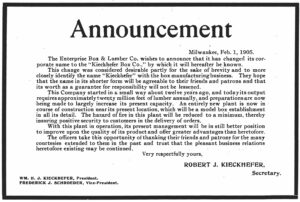

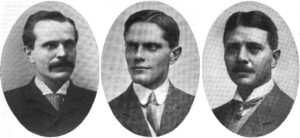

Across town, around 1892, A. H. Kayser, Charles Kayser, and William Schmidt formed the Enterprise Box and Lumber Company of Milwaukee. According to a trade publication, The Packages, in 1899 with his brothers busy with their own business ventures, William Kieckhefer and his brother-in-law Frederick Schroeder (son of John Schroeder, founder of the John Schroeder Lumber Company) became shareholders and incorporated the Enterprise Box and Lumber Co. with original owner Charles Kayser. Robert J. Kieckhefer, William’s eldest son, joined in 1902. In 1904, Kayser retired due to ill health and one year later the company was renamed the Kieckhefer Box Company.

Left to right: William H. Kieckhefer, president of Kieckhefer Box Company; Robert J. Kieckhefer, secretary; and Fred J. Schroeder, vice president. The Packages, Vol. 8 (February 1905): 37.

In an announcement made on February 1, 1905, Robert J. Kieckhefer proclaimed: “This change was considered desirable partly for the sake of brevity and to more closely identify the name ‘Kieckhefer’ with the box manufacturing business. They hope that the name in its shorter form will be agreeable to their friends and patrons and that its worth as a guarantee for responsibility will not be lessened.” The announcement also bragged about how the new plant was being constructed in a way that would reduce “the hazard of fire.”

In addition to producing all kinds of packaging boxes, the company manufactured hardwood bed frames, siding, ceiling and molding, cedar paving blocks, and other specialized wood products. In 1905, the company separated its two manufacturing operations by constructing a new factory two blocks away from the original building and bringing in the latest machinery to produce boxes and other wood specialties. When a fire destroyed their new plant in 1909, the Kieckhefers quickly rebuilt and continued on.

Following William Kieckhefer’s death on February 17, 1914, Robert succeeded as him president. William’s second-oldest son and Robert’s brother, John W. Kieckhefer (known as J. W.), was elected the company’s secretary-treasurer. However, differences between the brothers over company management resulted in Robert’s resignation. On June 23, 1915, J. W. Kieckhefer was elected president.

The 1920s:

Expansion and Acquisition

J. W. was described as “a marvelous leader” with a keen insight for business. His insight coupled with determination was what prompted J. W.’s push to convert major companies from using wooden boxes and containers to fiber ones, both solid and corrugated. Fiber being a relatively new shipping medium, most people were skeptical of it. But J. W. saw its advantages: it weighed less than wooden boxes or crates, it was easy to handle and seal; it was more durable; and—best of all—cheaper to produce.

John W. Kieckhefer. Milwaukee: Official publication of the Milwaukee Chamber of Commerce, Vol. 1 (May 1922): 18.

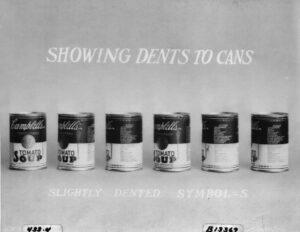

In the early 1920s, J. W. saw the opportunity to prove the advantages of fiber boxes. He approached the president of Campbell’s Soup Company, Dr. John Dorrance, claiming that he could save Campbell’s a lot of money if they switched to Kieckhefer’s solid fiber boxes. Dorrance didn’t think fiber could properly protect his product. One of J. W.’s colleagues described how he handled the Campbell’s Soup matter:

John went out and bought some cases of Campbell Soup in Boston, Chicago, St. Louis, [and] New Orleans. He took them out of the wooden boxes, put them into fiber containers and shipped them to Doc Dorance. Then he went down to see him. Doc Dorance said to him, “Just what I told you, some of those cans are damaged on the edge and the labels are torn and this and that.”

J. W. says okay, “I will ship you another series of your cans and this time I will take a blue pencil and [mark] it around the can wherever the can is damaged or the label is torn, then I can’t possibly know what damage would be in there.” So, he did that and when he went to see Doc Dorance again, Doc Dorance wanted to know what J. W.’s proposition was in getting his shipping container business.

J. W. persuaded Dorrance not only by proving his box’s durability, but also by demonstrating its advertising potential. Dorrance had spent a good amount of money on advertising his soup cans; he was sold on the fact that the smooth fiber containers allowed for beautiful print advertisements.

Thus, Kieckhefer opened its first container plant at Thorn and Copewood Streets, South Camden, New Jersey, just two miles away from Campbell’s Camden factory.

After his younger brother Herbert returned from service in the U.S. Army in France, J. W. asked him to become superintendent of the pilot plant. Herbert had studied engineering and commerce at the University of Wisconsin before entering the service where he was in charge of hospital maintenance and repairs and later was elevated to the U.S. Engineers. He was elected director, secretary, and treasurer of the new Kieckhefer Container Company, a subsidiary of Kieckhefer Box Company. This container company was the successor of the Kaukauna Pulp Company in Wisconsin, a sulphite pulp mill bought by J. W. in 1916 to produce the fiber needed for his boxes.

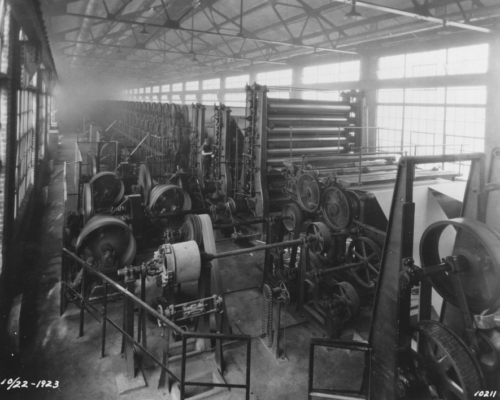

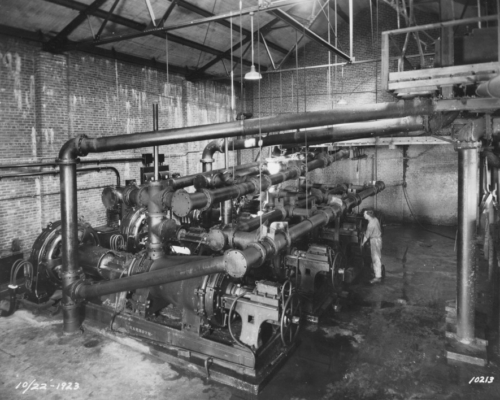

Business was booming and within two years, Kieckhefer Container Company had outgrown its Camden location. In 1921, the Kaukauna mill was sold and the money went toward building a new mill in Delair, New Jersey. In May 1922, construction of a new plant began in Delair on a historic spot on the Delaware River.

The plant, built by the renowned Irwin and Leighton Company of Philadelphia, was twice the size of the Camden plant and contained a board mill, container factory, and warehouses. The historic Fish home, which dated to the colonial era, was turned into an office and medical department. The machinery, with the exception of twelve Latham box stitchers, was of the company’s own manufacture.

Meanwhile in 1922, the Eddy Paper Company, a manufacturer of corrugated and solid fiber shipping containers located in Illinois, was reorganized as the Eddy Paper Corporation. Founded in 1906 by Henry Eddy under the name of The Michigan Corporation, it had operated in Kalamazoo and Three Rivers, Michigan, before moving to Illinois. In addition to container board produced in Delair, Kieckhefer had been buying some of its board from the Three Rivers mill. In 1927, J. W. acquired Eddy Paper, which had been struggling financially. He became president while his little brother, Walter, became secretary. According to John D. West in Story of a Century, this acquisition made them the second-largest producer of paper board shipping containers and also one of the oldest continuously operating ones in the country.

The 1930s and 1940s:

Boxes Go To War

Printed finished boxes, plain box sheets, and sheets scored and slotted, but unprinted or unstitched similar to those shipped to finishing plants.

Over the next couple decades, the Kieckhefer Container Company made great strides in the industry improving their products, developing machinery, and expanding their operation. By 1927, they were producing over a quarter of the nation’s solid fiber containers.

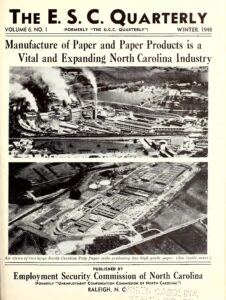

At this point, the Kieckhefer Company was motivated to start their own pulp mill. By 1933, J. W. was buying 300,000 tons of pulp from Scandinavia. When the Nazis took over in Germany that year, he became worried that “Hitler would start a war and his pulp supply would be cut off.” Thus, in 1937, the Kieckhefer and Eddy companies obtained a pulp and paper mill in Plymouth, North Carolina, called the North Carolina Pulp Company, of which Herbert Kieckhefer became director, secretary, and treasurer. This subsidiary was expanded and would go on to produce all the kraft liner board and “nine point” (paperboard that is 0.009 inches thick) for both companies.

Aerial views of the Kieckhefer’s new plant at the North Carolina Pulp Company in Plymouth, NC. The E.S.C. Quarterly, 6:1 (Winter 1948).

Kieckhefer Container commissioned a giant barge, built by the Dravo Corporation, for hauling baled woodpulp from the new mill in Plymouth to the factory in Delair, New Jersey. The first of its kind, this all-steel barge, christened Gretchen after Herbert Kieckhefer’s daughter, had the capacity to ship 888 bales, or 2,000 net tons, of wood pulp or other paper products.

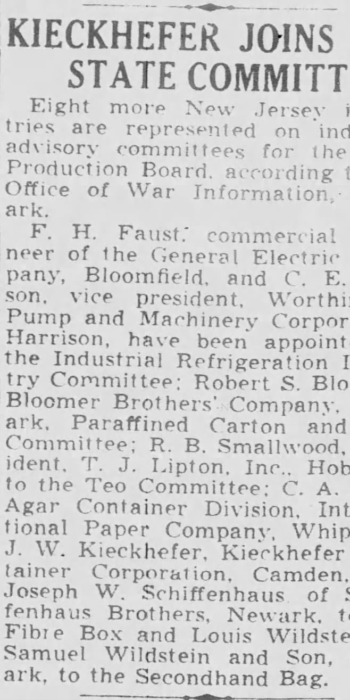

In 1939, Hitler did indeed start a war in Europe, just as J. W. predicted. When the United States entered the world war two years later, the Kieckhefers were eager to do their part and had representation on the War Production Board’s pulp and paper committee. The packaging industry in general was considered “essential” and, according to Herbert Kieckhefer, the company manufactured boxes and containers for guns and ammunition, as well as waterproof containers—stronger than corrugated boxes—intended to deliver supplies that, according to a newspaper report, would be thrown overboard at “combat points” at night, where they’d remain “in the water to be picked up by land forces during the daylight.” In addition, Kieckhefer Container Company collected more than 90,000 pounds of scrapmetal for Camden’s Industrial Salvage Committee.

In the years just before the United States entered the war, Kieckhefer was already experimenting with solid fiber dynamite boxes for use in the mining industry. Wood boxes—the industry standard—were less ideal due to their weight, bulkiness, and a general wood shortage. In addition, fiber boxes cost less than their wood counterparts.

Around 1939, J. W.’s son, Robert, started working for the Eddy Paper division as a salesperson and was tasked with promoting the solid fiber dynamite box to companies such as the Apache Powder Company near Benson, Arizona, a subsidiary of the mining company Phelps-Dodge Corporation. According to Robert, it took a while to convince them that the solid fiber dynamite box was the “wave of the future,” but eventually they were won over.

In 1943 the Courier Post of Camden, New Jersey, reported that Kieckhefer engineers had further adapted the product to create an asphalt-lined fiber board that could endure weather, water, and other hazardous conditions. This method was adopted by the rest of the industry so that supplies could be delivered to war zones in “immediately useful condition.”

Herbert Kieckhefer, whose engineering prowess had been instrumental in development of such solid fiber boxes, as well as the development of other products and machinery, was elected president of Kieckhefer Container Company and North Carolina Pulp Company in 1945, a position he would hold well into the next decade.

The 1950s:

Milk Cartons and a Merger

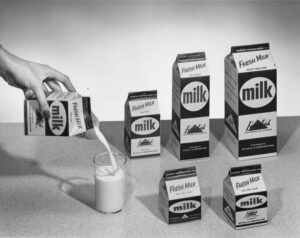

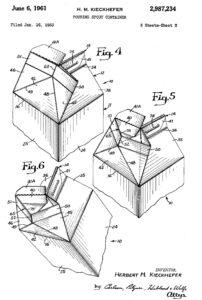

The end of the war would begin another era for Kieckhefer Container: making milk cartons. Robert Kieckhefer stated that the idea for the pitcher pour spout milk carton originated when he and his father were at a bar near J. W.’s home.

“My father and I were sitting in the bar at the Hassayampa Hotel (in Prescott, Arizona) one day drinking a bottle of beer before lunch. They had a bartender there who had to make an eggnog for a client and we watched him remove the staple from the top of the carton and pop the spout out. It was done very clumsily. I looked at my father and he looked at me and I said, ‘Do you see what I see?’ and he said, ‘Yes.’

We came back to my office which was only about 100 feet down the street and got a piece of plywood out of the garage to do the work on and had one of the secretaries go down and buy six quarts of milk, empty the milk out, and wash out the cartons. We took the staples out of the top and saw that this pitcher pour idea really worked. We slit the carton down the side seam and left the bottom and did the original engineering for this thing, [perforations], scoring, etc., right there in my office. After that, modifications were made on it by Herb Kieckhefer and others back at our labs in the East.”

“Pouring Spout Container” patent figures.

According to Herbert Kieckhefer, the company got into the milk carton business around 1939 when they acquired the Cherry River Paper company in Richwood, West Virginia. The Cherry River mill had been a supplier of milk carton board to accounts such as the Dixie Vortex Cup Company and Lily Tulip Cup Company. Much like the push to replace wooden boxes with fiber, J. W. believed that the more sanitary fiber milk cartons could replace the glass milk bottle, and the Cherry River Paper Company was key to taking on such an endeavor. Kieckhefer Container moved the mill’s operations down to Plymouth and started developing their version of the milk carton.

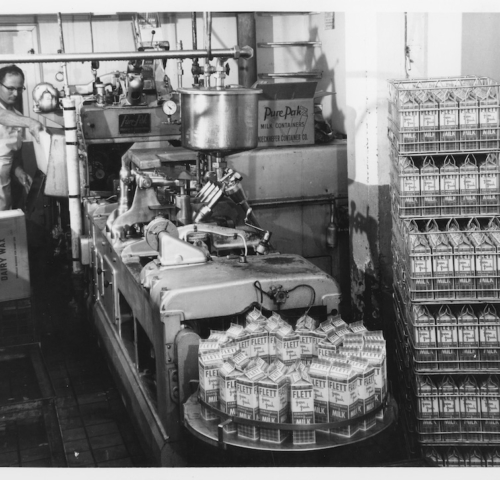

But due to licensing, there were some hold-ups when it came to manufacturing the fiber carton. The “paper bottle” was first patented in 1915 by John Van Wormer, which he called the Pure-Pak. The dairy industry fought Van Wormer’s invention due to their heavy investment in glass bottles. He sold the brand and rights to the American Paper Company in 1928, which failed to produce machines that could do the job properly. In 1934, American Paper approached the Ex-Cell-O Corporation, an equipment manufacturer, to help develop the machinery to produce the carton. Ex-Cell-O obtained the rights and patented the machines used to prepare and fill the cartons. Any further modifications to the design would need to be licensed from Ex-Cell-O.

Kieckhefer obtained a license from Ex-Cell-O and went to work. Partnering with a local Phoenix, Arizona, dairy company, Webster Dairy, Kieckhefer modified a piece of Ex-Cell-O machinery to produce the pouring spout top and a small batch was supplied to various chain stores. Soon these cartons were flying off their shelves.

However, officials at Ex-Cell-O thought the design would leak, and that people wouldn’t understand how the spout mechanism would work. Ultimately, Ex-Cell-O gave in when dairy businesses learned that these cartons could be produced for five percent less than other cartons at the time. In the end, this venture turned out to be extremely profitable for all.

Another product developed by Kieckhefer was the Quad-Lok box, which featured an extra-strong glue-lap joint in four corners. Quad-Lok containers were used in packaging everything from peanuts to washing machines. Quad-Lok boxes were also used for safely shipping a wide range of products, including freezers, TV sets, oil, crackers, fresh fruit, beer, soup, and soap.

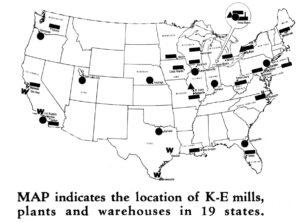

By the mid-1950s, the Kieckhefer-Eddy companies became one of the largest and most developed manufacturers and distributors of paperboard containers and cartons. Their growth did not go unnoticed.

In 1955, F. K. Weyerhaeuser became chairman of the Weyerhaeuser Timber Company board. F. K. was interested in diversifying the company into other areas and had his eye on Kieckhefer-Eddy. Howard Morgan, then vice president of pulp and paper for Weyerhaeuser Timber, had suggested one or two years earlier to J. W. Kieckhefer that their companies should merge. At the time, Kieckhefer plants were buying nearly half of Weyerhaeuser Timber’s bleach paperboard and a fifth of its unbleached containerboard.

It is reported that initially J. W. was not interested in a merger. He rebuffed overtures from several other companies. That changed in 1956. In an 1982 supplemental issue of the Roanoke Beacon (Plymouth, N.C.), Morgan recalled getting a phone call from Kieckhefer: “Howard,” [J. W.] said, “my brother Bill died yesterday in Milwaukee and I’m going back for the funeral. I’ve got high blood pressure and Bill’s death makes me worry. Are you still interested in a merger?”

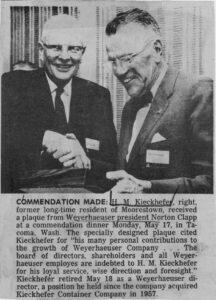

The merger between Kieckhefer Container Company-Eddy Paper Corporation and Weyerhaeuser Timber Company was advantageous for several reasons. Kieckhefer-Eddy relied heavily on kraft pulp—primarily created from sawmill leftovers—and their expanding operations would only increase that reliance. Weyerhaeuser had the means to supply it. Additionally, the merger fit Weyerhaeuser Timber’s policy at the time to “provide and utilize a continuous forest crop efficiently and completely.” In merging with Kieckhefer-Eddy, Weyerhaeuser could then use its wood to a fuller potential. It would also give Weyerhaeuser Timber the opportunity to market its forest products directly to customers. The merger was completed on April 30, 1957, with Kieckhefer-Eddy operating as its own division. As a result, Robert and Herbert were elected to the Weyerhaeuser board of directors, Herbert became senior vice president of the division and Howard Morgan became president. Robert would serve as vice president of the Western Region. The merger also marked the end of J. W.’s 50 years of illustrious leadership within the paper industry.

Legacy

In 1959, it was decided that Weyerhaeuser Timber Company would shorten its name to Weyerhaeuser Company—to better reflect the full scope of the firm’s business—and the Kieckhefer-Eddy name would be discontinued. Instead, their operations were rechristened the Shipping Container Division—a name that described their function and products in the simplest terms possible.

As senior vice president of the Shipping Container Division, Herbert devoted his time to research and development, and to the investigation of new businesses and new products. He retired from this position in 1962, and continued to serve on the Weyerhaeuser board of directors until 1965.

Robert served as a member of the Weyerhaeuser board for 33 years until he retired in 1990, and was a member of the Executive Committee for more than 25 years. He later likened a merger to a marriage, noting, “Not all marriages work out, but this has been a happy one.” His long service on the board certainly supports that assertion. He was replaced on the board by his son, John I. Kieckhefer, who served on the board for 27 years.

Looking back, the Kieckhefers have had a fruitful and formidable journey, one that helped transform how people move and even consume products—everything from dynamite in a war zone to milk on the breakfast table. Starting with a small factory in Wisconsin, several generations of the Kieckhefer family led the shipping and container industry in the first half of the 20th century with their visionary leadership, innovation, and savvy up until—and beyond—their partnership with the Weyerhaeuser Company.

Resources

To see all digitized images of the Kieckhefer Container Company, click here.

Weyerhaeuser Company Records:

“Fresh Fruit: handle with care.” Weyerhaeuser News, no. 40 (March 1959): 22-23.

“Full crop utilization reaches end-consumer with Kieckhefer-Eddy-Weyerhaeuser Merger.” Weyerhaeuser News, no. 35 (June 1957): 2-3.

Herbert M. Kieckhefer, Biographical Files, Weyerhaeuser Company Records.

Kieckhefer-Eddy Division, 1957, F. K. Weyerhaeuser Papers, 1942-1960, Weyerhaeuser Company Records.

Kieckhefer-Eddy files, 1933-1937, Weyerhaeuser Company Records.

Kieckhefer-Eddy Merger, 1957, George S. Long Jr. Papers, 1901-1980, Weyerhaeuser Company Records.

Oral history interview with Herbert M. Kieckhefer and Joseph A. Auchter. Interview by A. J. McCourt in Scottsdale, AZ, May 9, 1975. Weyerhaeuser Company Records.

Oral history interview with Herbert M. Kieckhefer. Interview by A. J. McCourt in Paradise Valley, AZ, February 19, 1976. Weyerhaeuser Company Records.

Oral history interview with Joseph A. Auchter. Interview by A. J. McCourt in Phoenix, AZ, February 19, 1976. Weyerhaeuser Company Records.

Oral history interview with Robert H. Kieckhefer. Interview by A. J. McCourt in Phoenix, AZ, February 20, 1976. Weyerhaeuser Company Records.

“Quad-Lok delivers the goods.” Weyerhaeuser News, no. 43 (March 1960): 3-4.

Twining, Charles E. F.K. Weyerhaeuser: A Biography. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1997.

Outside Resources:

Bruce, William George. History of Milwaukee, City and County, Volume 2. Milwaukee: S. J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1922.

Bruce, William George. History of Milwaukee, City and County, Volume 3. Milwaukee: S. J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1922.

Boxboard. Chicago: Beaton, Godron, Middleton & Rehm.

Courier Post [newspaper]. Camden, New Jersey.

Chaney, Jim. “N.C. Pulp Co. Expanding Pulp-Paper Production.” The E.S.C. Quarterly 6, no. 1 (1948): 1, 8.

Chertoff, Emily. “The Surprising History of the Milk Carton.” The Atlantic, August 1, 2012.

“Ferdinand A. W. Kieckhefer,” The Successful American 5, no.1 (January 1902): 34-36.

Fibre Containers. Chicago: Board Products Publication Company.

“The Kieckhefer Container Co. Cherry River Division.” Pacific Electric Magazine, Mar-April 1948, 4.

“Kieckhefer, Ferdinand August William, 1852–1919.” In Dictionary of Wisconsin Biography. Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1960.

Kieckhefer, Herbert M. Pouring Spout Container. US Patent 2,987,234 A, filed January 16, 1953, and issued June 6, 1961.

Morning Post [newspaper]. Camden, New Jersey.

Nebelsick, Alvin L. A History of Belleville. Belleville, IL: Township High School and Junior College, [1951?].

The Packages. Milwaukee: The Packages Publishing Co.

Paper Trade Journal. New York: Vance Publication Corp.

Robertson, Gordan L. “The Paper Beverage Caron: Past and Future.” Food Technology Magazine, July 1, 2002.

Stove and Hardware Reporter. St. Louis: Stoves and Hardware Publishing Co.

Twede, Diana, Susan E. M. Selke, Donatien-Pascal Kamdem, and David Shires. Cartons, Crates and Corrugated Board: Handbook of Paper and Wood Packaging Technology. Lancaster, PA: DEStech Publications, 2015.

United States War Production Board. Directory of Industry Advisory Committees: As of January 23, 1943. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1943.

United States National Production Authority. Historical Reports on Defense Production, Issues 30-34. Washington, DC, 1953.

West, John D. “Manitowoc County industrial progress.” In Story of a Century, 1848-1948: Manitowoc County During Wisconsin’s First Hundred Years, edited by Manitowac County Centennial Committee, 58-69. [Manitowoc?, WI]: Manitowoc County Centennial Committee.

Western Historical Company. History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Chicago: Western Historical Company, 1881.

“Weyerhaeuser in North Carolina, 1957-1982.” The Roanoke Beacon, supplement April 28, 1982.

Woodburn, J. G. Tests of Fibre Boxes for the Kieckhefer Box Company. Madison, WI: U.S. Forest Service, Forest Products Laboratory, 1921.