The Monongahela at 100: How Its Signature Event Changed American Forestry

By Guest Contributor on April 30, 2020

The Monongahela National Forest was established on April 28, 1920. Historian Char Miller has adapted a chapter from the book

The Monongahela National Forest was established on April 28, 1920. Historian Char Miller has adapted a chapter from the book America’s Great National Forests, Wilderness & Grasslands

, with photographs by Tim Palmer (Rizzoli, 2016), to mark the centennial.

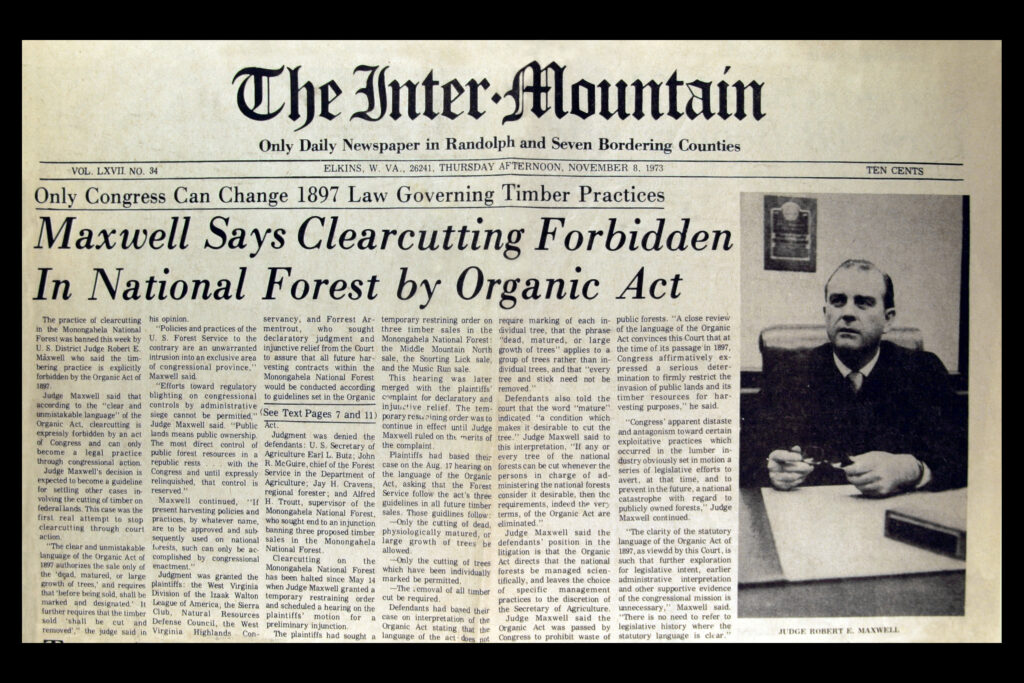

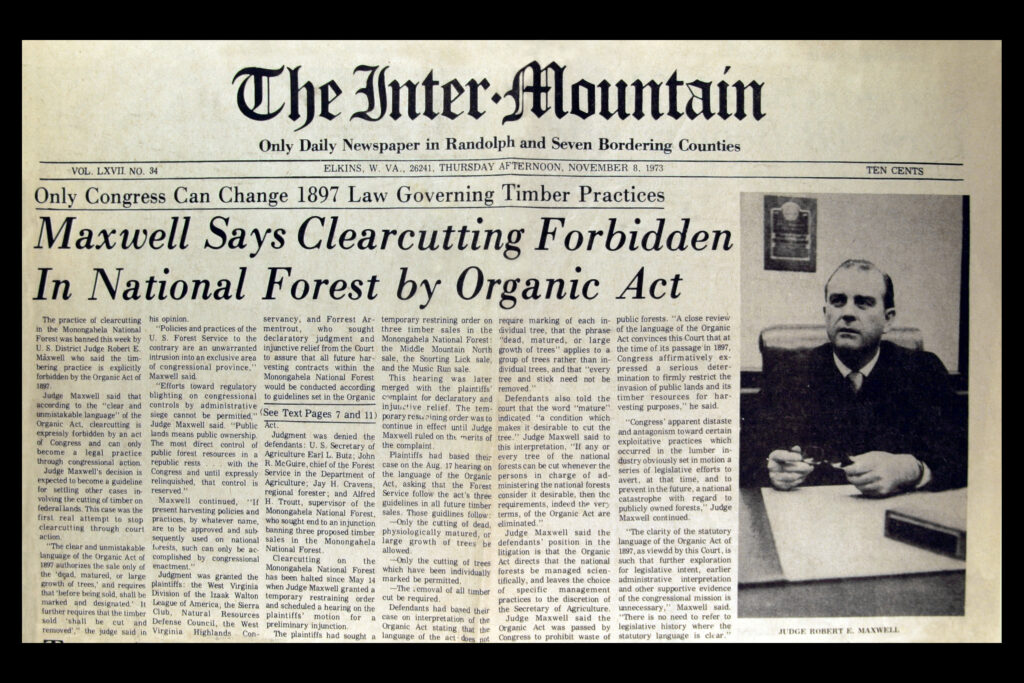

The banner headline on the front page of the Elkins, West Virginia, newspaper for November 8, 1973, could not have been more direct or revelatory: “Maxwell Says Clearcutting Forbidden In National Forest by Organic Act.” Only a few months before, federal judge Robert Maxwell had heard arguments in

Izaak Walton League v. Butz. His decision sent shock waves through Region 8 of the U.S. Forest Service and soon across the country. Nearly a half-century later the Monongahela Controversy still reverberates. It’s worth revisiting as the Monongahela National Forest marks its centennial. This lawsuit may have been the single most important event in the forest’s history.

Courtesy of “The Greatest Good” film website.

At the time of the lawsuit, 784,000 of the Monongahela’s 820,000 acres were classified as commercial forest land. The Izaak Walton League’s case, however, focused on three proposed timber sales that covered a mere 1,077 acres—428 of which were to be clearcut, the plaintiffs argued, in violation of the Organic Act.

1 The act—the foundation upon which seventy-five years of federal forest policy stood—had identified the objectives by which the national reserves (now national forests) would be managed: “to improve and protect the forest within the boundaries, or for the purpose of securing favorable conditions of waterflows, and to furnish a continuous supply of timber for the use and necessities of citizens of the United States.”

2

Though the Monongahela National Forest was not formally established until April 28, 1920, its first 7,200 acres—known as the Monongahela Purchase Unit—had been acquired in 1915 under the aegis of the Weeks Act of 1911. This legislation, which enabled the federal government to purchase badly managed land in high-country watersheds from willing sellers, was again the funding source that by the mid-1920s had expanded the Monongahela to 150,327 acres. The management goal in West Virginia and elsewhere, wrote W. W. Ashe, who as secretary of the National Forest Reservation Commission oversaw Weeks Act purchases, was to restore the “dreary waste as has been the fate of much of the fir- and spruce-clad slopes” in the Allegheny Mountains.

3 Today, the national forest protects 921,000 acres and continues to sustain local and regional watersheds, most notably the headwaters of the Potomac River, the main source of drinking water for Washington, DC, home to the Forest Service’s national headquarters.

4

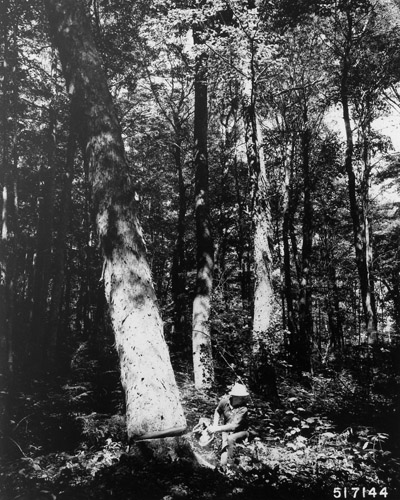

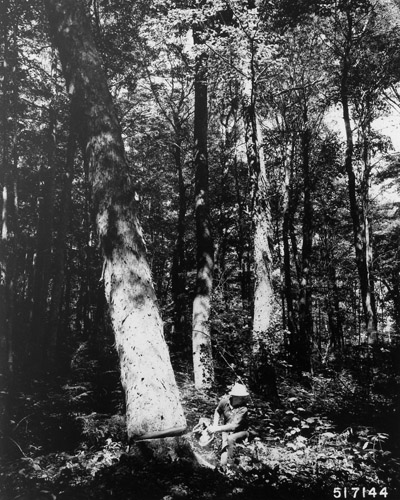

Felling a tree on the Monongahela, 1966. (FHS Photo Collection, R9_517144)

But it was not water that was the paramount issue in 1973, it was timber. Those arguing against clearcutting pointed out that the Organic Act only allowed the harvest of “dead, physically mature and large growth trees individually marked for cutting.” Judge Maxwell concluded that the agency’s clearcutting practices violated this provision of the Organic Act, a decision that the U.S. Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld two years later.

The Monongahela Controversy was linked to an array of legal challenges to the Forest Service’s postwar get-out-the-cut campaign, a pattern of accelerated harvesting designed to bring large quantities of wood to market in response to the nation’s construction boom. Backed by scientific research indicating that even-aged management of forests (that is, clearcutting) would produce a better quality and higher volume of timber, the agency managed large-acreage sales using this practice on its forests fairly uniformly across the country. Wielding more powerful chainsaws and firing up military-surplus bulldozers to build roads deep into the backcountry, loggers on the Monongahela and elsewhere removed billions of board feet every year. In 1945, loggers cut approximately 2 BBF on the national forests, in 1960 the total was 9.3 BBF, and by the mid-1980s the figure had soared to 18 BBF. Even one of its advocates recognized that clearcutting left behind “an aura of total devastation.”

5

Among the first to blow the whistle was a clutch of squirrel and

turkey hunters in West Virginia. They were infuriated that intense logging had rendered unusable their traditional hunting grounds on the Monongahela, and they were angered that the Forest Service effectively handed over this communal, multi-use resource to single-use timber companies. They were worried that the agency, which had done so much to restore what in the early twentieth century had been a badly burned and cut-over landscape on the Allegheny Front Range, was destroying these now-healthy, resilient forests. They lobbied the West Virginia legislature to secure redress, and during the 1960s it responded with a series of hearings and resolutions to rein in the Forest Service. The agency cavalierly ignored these cautions, taking its cue from its chief,

Edward Cliff, who met with and subsequently dismissed the pleadings of a delegation of West Virginia hunters, conservationists, and politicians. Their pleas, he later declared, were “a very self-centered protest from a very small segment of the population who wanted the national forest to be managed just for their own personal pleasure.” Cliff later would regret his misreading of the range and depth of their concerns and their capacity to galvanize public opinion but seemed to never forgive them either.

6

Rebuffed, the West Virginians sued in federal court through a local branch of the Izaak Walton League, a national conservation organization, and the suit gained support throughout the state and was joined by others including the National Resources Defense Council and the San Francisco–based Sierra Club, ensuring that the case would have national implications. Judge Maxwell’s decision in support of the legal challenge, and the appeal court’s sustaining of it, caught the Forest Service completely off-guard. It was the first time that its expertise had been adjudicated and found wanting.

A family fishes the South Branch of Potomac River for trout in the Smokehole Recreation Area, July 1, 1966. In the 1950s and 1960s, the general public increasingly engaged in recreational activities like hunting and fishing, making a clash between timber and nontimber users of national forests almost inevitable. (FHS Photo Collection, R9_514698)

Although the appeals court’s decision technically only applied to Fourth Circuit, its decision effectively, if temporarily, shut down the agency’s timber sales program nationwide. Aware that this might be the result, and in acknowledgement that the Organic Act might be outdated, the court advised that the “the appropriate forum to resolve this complex and controversial issue was not the courts, but Congress.” With that, the battle that had erupted on the Monongahela shifted to Capitol Hill, and two legislative initiatives were the result: the Resources Planning Act (1975) and the National Forest Management Act (1976). Together these laws required every national forest to produce a management plan, which would include an Environmental Impact Statement that would consider and weigh ecological and hydrological—as well as social—values. In turn these documents must be vetted by the public; if their goals and actions were in dispute, they must be revised accordingly. For the agency, which hitherto had determined when and how the national forests would be managed, these new laws signaled the beginning of a more collaborative, open, and transparent process, though it’d take the Forest Service several years to fully embrace that process.

7

The controversies did not stop, however. Instead, in West Virginia, as well as in New Hampshire, Texas, Montana, and Washington State—and points in between—individual forest plans ever since have been challenged in public venues and federal courts. These long-running battles are one of the costs of a more democratic process, and from a certain perspective has created a sense of gridlock, leading some to argue that such debates are antithetical to sound management, both locally and system-wide. But the Monongahela and other national forests are public lands and require public scrutiny to insure that their management adheres to what the citizenry values. By having to accept that premise, this complex process can be messy and incomplete. By having to acknowledge that top-down management of the forests, with its command-and-control ethos, was as outdated as the 1897 Organic Act, the Forest Service began to undergo a vital transformation. A transformation that resulted in good part because one day in 1964, hunters headed up into the Monongahela National Forest and came down ready to fight for the land and their rights in its bounty.

Char Miller is the W. M. Keck Professor of Environmental Analysis at Pomona College and the author of Ground Work: Conservation in American Culture.

Notes

1. Gillian Mace Berman and Melissa Conley-Spencer,

Monongahela National Forest, 1915–1990 (Morgantown, WV: West Virginia University Public History Program, 1992), 148.

2. Quoted in

West Virginia Div. of Izaak Walton League, Inc. v. Butz, 367 F. Supp. 422 (N.D.W. Va. 1973), https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp/367/422/1425532, accessed April 28, 2020.

3. W. W. Ashe, “The Creation of the Eastern National Forests,”

American Forests, September 1922, 523.

4. Christopher Johnson and David Govatski,

Forests for the People: The Story of America’s Eastern National Forests (Washington, DC: Island Press, 2013), 187–206.

5. Kathryn Newfont,

Blue Ridge Commons: Environmental Activism and Forest History in Western North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012), 130–38.

6. Edward P. Cliff, Ronald B. Hartzer, and David A. Clary,

Half A Century in Forest Conservation: A Biography and Oral History of Edward P. Cliff (Washington, DC: USDA Forest Service, 1981); Newfont, Blue Ridge Commons, 135.

7.

West Virginia Division of the Izaak Walton League of America, Inc. v. Butz, No. 74-1387 (4th Cir. August 21, 1975), http://elr.info/sites/default/files/litigation/5.20573.htm accessed May 11, 2014.

The Monongahela National Forest was established on April 28, 1920. Historian Char Miller has adapted a chapter from the book America’s Great National Forests, Wilderness & Grasslands, with photographs by Tim Palmer (Rizzoli, 2016), to mark the centennial.

The banner headline on the front page of the Elkins, West Virginia, newspaper for November 8, 1973, could not have been more direct or revelatory: “Maxwell Says Clearcutting Forbidden In National Forest by Organic Act.” Only a few months before, federal judge Robert Maxwell had heard arguments in Izaak Walton League v. Butz. His decision sent shock waves through Region 8 of the U.S. Forest Service and soon across the country. Nearly a half-century later the Monongahela Controversy still reverberates. It’s worth revisiting as the Monongahela National Forest marks its centennial. This lawsuit may have been the single most important event in the forest’s history.

The Monongahela National Forest was established on April 28, 1920. Historian Char Miller has adapted a chapter from the book America’s Great National Forests, Wilderness & Grasslands, with photographs by Tim Palmer (Rizzoli, 2016), to mark the centennial.

The banner headline on the front page of the Elkins, West Virginia, newspaper for November 8, 1973, could not have been more direct or revelatory: “Maxwell Says Clearcutting Forbidden In National Forest by Organic Act.” Only a few months before, federal judge Robert Maxwell had heard arguments in Izaak Walton League v. Butz. His decision sent shock waves through Region 8 of the U.S. Forest Service and soon across the country. Nearly a half-century later the Monongahela Controversy still reverberates. It’s worth revisiting as the Monongahela National Forest marks its centennial. This lawsuit may have been the single most important event in the forest’s history.