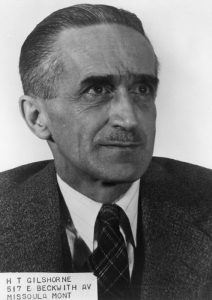

September 11, 1893: Forest Fire Researcher Harry Gisborne’s Birthday

Family and friends probably had to be careful when they lit the candles on a birthday cake for Harry Gisborne. As the first true specialist in forest fire research in the country, he might have held court about fire danger while the candles burned down to the icing. Kidding aside, Gisborne’s work included fire danger rating systems, prediction of fire behavior, fire weather forecasting, fire control strategy, fire control organizations, weather modification, fuels studies, and the application of fire retardants. His impact on the study and understanding of forest fires was so great, so marked, that his career span of 1922 to 1949 is known as the “‘Gisborne Era’ of forest fire research.”

Harry Gisborne, aka, “Gis”

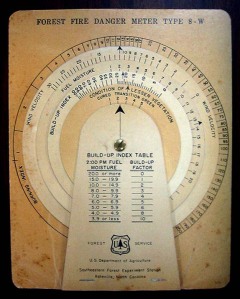

Gisborne’s work and career are well documented: born in Vermont in 1893, he graduated from the University of Michigan’s School of Forestry in 1917 and then briefly worked in Oregon as a timber cruiser before serving in World War I with the Tenth Engineers. He returned home and held a succession of research and staff positions before being assigned to the Northern Rocky Mountain Forest Experiment Station at Priest River, Idaho, in 1922. He quickly established a personal creed that guided his career and work: research was useless unless it addressed real problems and could produce results for immediate application. He spoke frequently with field foresters to understand “real problems” and turned out inventions, findings, and data that lived up to that creed. The fire danger meter he invented in 1939 led to the development of the National Fire Danger Rating System and made possible advances in understanding of fire meteorology, weather and lightning forecasting, fuel types and fuel moisture content, and fire behavior. Though the research data came from local sites near Priest River, his work had a national and even international impact.

This Fire Danger Meter Type 8-W is in the National Fire Danger Rating System Collection.

Gis’s many coworkers described him as sarcastic, outspoken, irascible, “and nearly as demanding of perfection from others as he was of himself. And yet, he inspired a legacy of devotion and fond memories that is truly remarkable…,” according to his biographer Mike Hardy (the biography, published by the U.S. Forest Service, is available through Google Books.) Gisborne himself said he was the burr under their tails that motivated them to do their best for him and science.

World War II brought a pause in his research and a corresponding drop in funds. But both accelerated after the war ended. The Forest Service’s obsession with fighting all fires under the 10 a.m. policy, which Gisborne opposed, ironically meant more funding and tools at his disposal. Surplus aircraft enabled experiments in aerial fire fighting and experiments in cloud seeding.

Ultimately, Gisborne’s hard-driving nature would lead to his demise and also forever link him to the tragic incident at Mann Gulch. Following the death of 13 smokejumpers and a forest guard in the August 1949 Mann Gulch fire, the Forest Service wanted to understand what happened there. Gisborne read all available reports on the incident before visiting the site on November 9, 1949. He wanted to walk through the burned area to see things for himself but was advised not to go into the rugged valley because of poor health. He collapsed there and died. Some say that he’s the 14th victim of the Mann Gulch fire.

The Harry Gisborne memorial marker in Mann Gulch is the first one encountered as you hike in from the Missouri River. (Courtesy of the author)

This marker stands at the spot where he died. But that’s not where Gisborne wanted to spend eternity. He had left instructions and a photo in his desk drawer indicating where he wanted his ashes spread—on a mountain near Priest River. A year later, the mountain was renamed in his honor and a brass memorial marker placed. It declares him a “Pioneer in Forest Fire Research.” Indeed, he was the last of that field’s pioneers and one of its greatest.

FHS has many resources on Harry Gisborne and his fire research. Most are found on our “U.S. Forest Service Fire Research” page. The National Fire Danger Rating System Collection holds materials collected between 1911 and 2004.

To learn more about Harry Gisborne, watch this film “short” from “The Greatest Good” documentary.