The Oberlaender Trust and American Forestry

Tweet Share

Establishing The Trust

In the early 20th century, Gustav Oberlaender built his fortune in the hosiery industry, but he earned a legacy through philanthropy. Though not a forester himself, his charitable acts linked his name to the field of forestry and, indirectly, have had a lasting impact on the management of American forests and wildlife.

Oberlaender (1867-1936), a German immigrant with strong connections to his home country, donated $1 million ($16 million in 2021 dollars) to establish the Oberlaender Trust in 1931. Operating under the Carl Schurz Memorial Foundation established the year prior, the Oberlaender Trust specifically dedicated itself to fostering transatlantic relationships. This was done by financing travel between Germany and the United States for intellectuals and municipal leaders. Grants were given to “American citizens who are actively engaged in work that concerns the public welfare … and who will profit by a period of study in a German-speaking country.” Because some funding was provided “for the publication of such reports and findings as, in the opinion of the Board of Trustees, would be of special help to the American people,” participants wrote articles or had excerpts from their reports to the Trust published, leaving behind a record of their impressions and assessments of different aspects of a prewar Europe.

In the mission statement of his namesake trust, Oberlaender identified forestry as a principle field of public welfare requiring cross-cultural networking and learning. Including forestry made sense. While serving as secretary of the Interior in the 1870s, Carl Schurz—the prominent German immigrant for whom the memorial foundation was named—had urged the federal government to take up forestry to provide timber for future generations. For American foresters in the 1930s grappling with ecological issues in many of its forested regions and battling economic woes throughout the nation’s lumber industry, returning to what was considered the ‘birthplace of forestry’ in search of answers seemed a natural thing to do.

Accordingly, the forestry exchange program began with a renowned German forester touring the United States in 1934. The Trust subsequently sponsored four tours to Europe: American lumbermen in 1934, U.S. Forest Service leaders in 1935, foresters and industry professionals in 1936, and, last, forestry professors and researchers in 1937. The forestry exchange concluded after a group of German forest officials visited the United States in 1938.

Although this exchange lasted a short time, many notable foresters and professionals, including Aldo Leopold, benefited from the transatlantic trips and the connections made possible through the fund. However, the coinciding of the first Oberlaender trips beginning shortly after the Nazi Party came to power did not go unnoticed by critics. Although the leaders of the Carl Schurz Memorial Foundation and the Oberlaender Trust made efforts to distance themselves from the Third Reich, suspicions around the overall program garnered public criticism and resulted in official inquiries from the United States government.

German Forester Visits America (1934)

Tour of American Lumbermen (1934)

United States Forest Service Grants (1935)

Second Foresters’ Tour (1936)

Forestry Grants (1937)

German Forestry by Dr. Franz Heske (1938)

German Forestry Officials visit the United States (1938)

Lasting Legacy of the Oberlaender Trust

German Forester Visits America (1934)

“To study American forestry problems before conducting a tour of Germany with a group of American foresters; and to lecture”

Heske [standing] translating Baron Von Kalitsch‘s description of the forest. (Photo from Tom Gill album of Oberlaender Trust trip 1936).

The exchange began with a visit to the United States by Dr. Franz Heske. Since 1928 Heske had served as the director of the Institute of Forest Management and Professor of Forest Science at the Forest Academy in Tharandt, Germany. In 1931, he had founded the Institute of Foreign and Colonial Forestry and its journal, the Zeitschrift für Weltforstwirtschaft (Journal of World Forestry). Due to his demonstrated interest in forestry around the world, Heske was invited to the United States to survey American forestry in the summer and fall of 1934. He subsequently acted as director for the three tours of American foresters over the next several years.

His survey of American forests and his leadership of Oberlaender tours culminated with the book German Forestry, published by the Oberlaender Trust for an American audience, in 1938.

Tour of American Lumbermen (1934)

“To tour large and important forests of Germany and Austria and to study sustained yield management.”

The inaugural tour of American foresters in Europe sent a group of twelve men and their companions to Germany, Austria, and Czechoslovakia. For the month of August, the Oberlaender party traveled under the guidance of Dr. Heske to large estates, forest lands, and forestry museums and schools to learn about German practices.

On the Hamburg-American liner “New York” bound for Cuxhaven (July, 1934)

Reflections from John W. Watzek Jr.

John W. Watzek Jr., future president of the National Lumber Manufacturers’ Association and director of the American Forestry Association, wrote about his experiences in a 1936 letter. Intended as advice for John Woods (who would travel with the second foresters’ tour), the letter contains reflections on the people and places the party visited:

One of the smaller forests that you will probably visit that is near Berlin is called Barenthoren. Von Kalitsch, whose home that is, is an old man over eighty. He will be more than anxious to show you the results he has obtained from natural reforestation and from not allowing his soil to be depleted by people picking up twigs for firewood in his forest. There is an excellent example here in the same stand of timber, part of which is owned by the Kaiser, where firewood had been gathered for years and just what damage this had done to the growth. Barenthoren is famous because Kalitsch was the first man in Germany, this was only about 1880, who conceived the idea of not cutting a forest clean and replanting. In other words, he followed the Swedish method of natural regeneration long before anyone else in Germany did.

You will probably go to the Schaffgotsch estate which is in Silesia near the Riesengebirge. This is one of the largest forests that we were on. Some 58,000 acres comprise this estate, mainly Spruce, and beautiful Spruce at that. There will be a whole corps of foresters that will meet you particularly in these larger estates, and they are always headed up by an Oberforstmeister. It is quite the thing to be a forester in Germany. Your reputation is made and rightly so because you not only have to be a University graduate but also have long years of experience in working up through the various private forestry organizations.

- Spruce of the Isergebirge.

- Peeling spruce pulpwood. Riesengebirge.

- Felling a spruce. Schönberg estate.

Reflections from The American-German Review

Watzek and the other participants published excerpts from their reports in the December 1934 edition of The American-German Review. The men reflected on the value of their experiences abroad and shared lessons learned. They all admired the efficiency with which Germans managed their forests and many of them commented on how that benefitted both the country as a whole and the workers on the estate forests they visited in particular. Several of the excerpts touted the advantages of the German system of land ownership when it came to forest management:

This trip has opened up excellent opportunities, developed fine contacts with leading German forest owners and foresters, and focused thought on German forestry experience in many directions useful to the United States…. We have much to learn from Germany in the planning and administration of forest properties.

Wilson Compton, Secretary-Manager of the National Lumber Manufacturers’ Association

15.3% of all forests in Germany are community-owned. These provide healthful recreation facilities for the people and revenue for local government through the sale of products grown. Most important, they provide work for the community during the depressing periods. In America all properties (forests) are held as the exclusive possession of the present owner. In Germany all properties are regarded as belonging not merely to the present owner but to future generations and are only under management and protection of the present owner.

L. K. Pomeroy, President of Ozark Badger Lumber Company

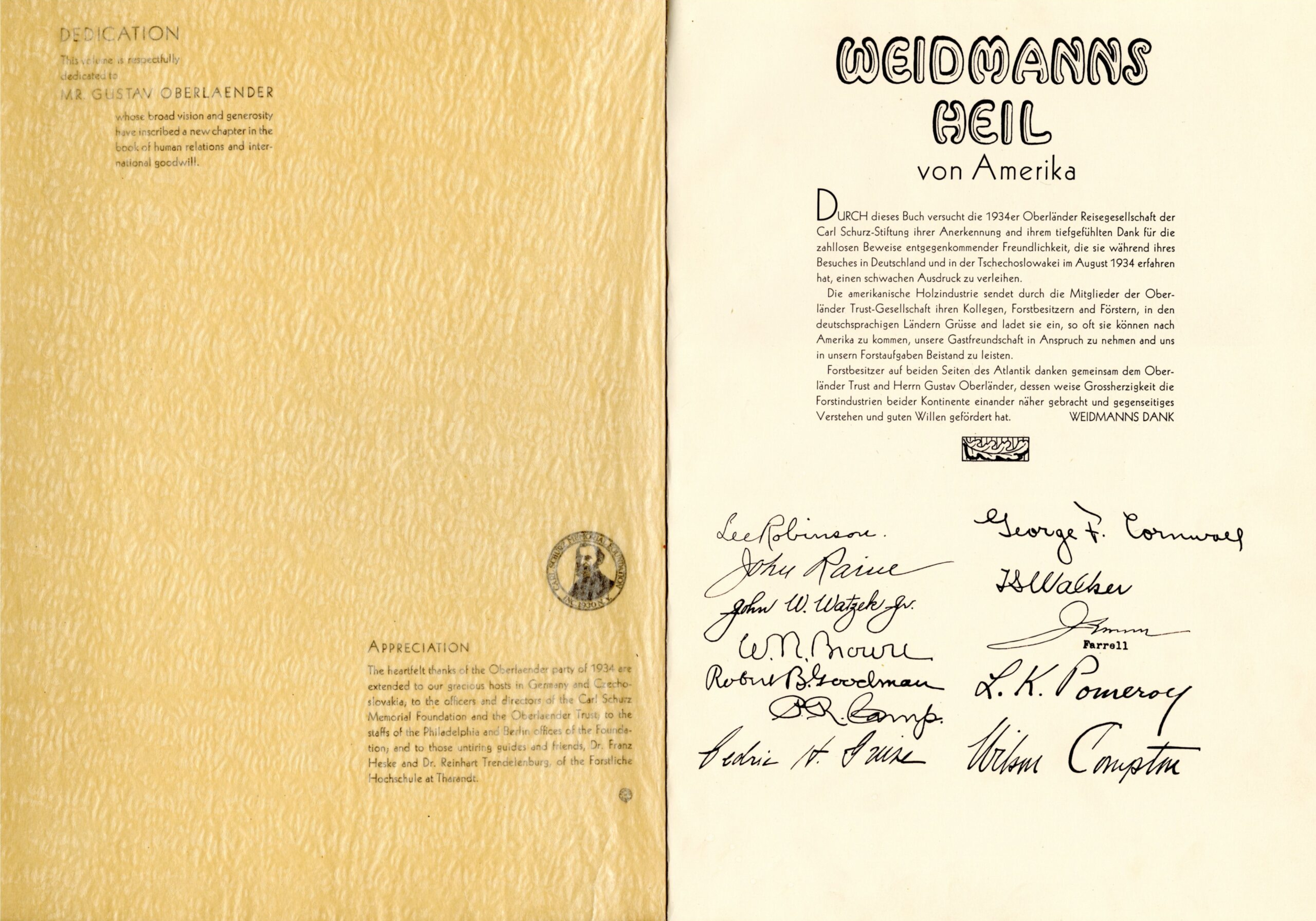

As a souvenir of their travels and a gift to their hosts, the 1934 Oberlaender Fellows published the “Weidmanns Heil von Amerika,” which documented their travels through Europe.

United States Forest Service Grants (1935)

“Grants were made to the following men from the United States Forest Service”

Grantees of 1935 Oberlaender Trust funds

Instead of leading another group of lumbermen on a tour of German and Austrian forests, the Oberlaender Trust funded travel for six U.S. Forest Service associates to tackle specific issues. Each man had a unique itinerary and met with different European officials over the course of three to six months. On the recommendation of Forest Service leaders, Aldo Leopold was invited to study game management, even though he’d resigned from the agency in 1928. Five years after resigning, he was appointed professor of game management at the University of Wisconsin, the first such position in the country. He already had a national reputation in the field he established by 1935.

Reflections from L. F. Kneipp

In a letter to the Oberlaender Trust, L. F. Kneipp, who oversaw the Forest Service’s land purchase program and had made the trip to study community use, wrote:

In the course of the tour I personally visited and observed conditions on thirty of the largest and most important forests in Germany, Austria, and Czechoslovakia; established contacts with perhaps fifty of the men who are important in the fields of forestry and related forms of land use, either as public officials or as owners and managers of forest properties and enjoyed the opportunity to review many exceedingly interesting plans of forest management which set forth in detail all of the principles of planned forest management in which the Germanic countries excel.

Left to right: William Sparhawk, Aldo Leopold, Clarence Forsling, Leon Kneipp, and Edward Carter.

Reflections from C. L. Forsling

C. L. Forsling, a researcher with the Forest Service since 1915 then serving as director of the Appalachian Forest Experiment Station, went to Europe to study technical problems. In a later interview he recalled:

It was worth the time and effort to get to know the European foresters. I didn’t confine myself to the German-speaking countries; I took a couple of weeks and visited Sweden, where my parents were born. In my opinion, there was more for Americans to learn from Swedish foresters than from German foresters. In Germany the most common practice was to clearcut and replant, generally using the same species in planting after planting. We saw forests that were in the third generation of single species, mostly Scotch pine or spruce. The research foresters had discovered after repeated monospecies that planting of conifers was playing havoc with the forest soils by not returning enough organic matter to the soil. The foresters were trying to introduce broad-leaved tree species which annually add leaf fall to the soil.

Here are a selection of photos from the C. L. Forsling papers:

Reflections from Aldo Leopold

This 1935 trip to Europe was Aldo Leopold’s first and only time abroad. Leopold had worked for twenty years as a forester in Arizona and New Mexico, during which he fostered his interests in wildlife and wilderness before taking up game management as a profession in 1928. In an unpublished document entitled “Wilderness,” found in his desk after his death in 1948, Leopold reflected upon his experience in Germany. His impressions sharply departed from what others had come away with. In particular, the two German forestry policies, Dauerwald and Naturschutz, affected his perception of wilderness. Biographer Susan Flader summarized this in an 1991 article for American Forests magazine:

Leopold was impressed by much of what he saw in Germany, but he was also profoundly unsettled by it. Germany, after a devastating experience with soil sickness brought on by wholesale conversion to monotypic plantations of spruce or pine, had shifted around 1914 to a more ecologically informed policy of Dauerwald or “permanent woods”—mixed forests naturally reproduced—coupled with an aggressive, nationalistic Naturschutz movement aimed at preserving small remnants of native flora and fauna.

[Forest stand, Europe.] (From the Clarence Forsling Papers.)

One cannot travel many days in the German forests, either public or private, without being overwhelmed by the fact that artificialized game management and artificialized forestry tend to destroy each other.

In “Wilderness,” he explained the “artificialization” he witnessed. He noted an “unnecessary outdoor geometry” that the Germans began applying to their forests hundred of years ago. Rows of trees, straight lines, and homogeneous blocks dominated the landscape. No regard was given to the natural messiness of mixed-age forests or meandering streams. The forests were clean, well-kept, and sharply delineated.

Leopold also made the more subtle observation about the lack of wilderness in Germany with the disappearance of predator species. The United States was heading down the same path of eliminating predator species for the artificial abundance species. But at what cost? Leopold wrote:

Before our American sportsmen and game keepers and stockmen have finished their self-appointed task of extirpating our American predators, I hope that we may begin to realize a truth already written bold and clear on the German landscape: the success in most over-artificialized land-uses is bought at the expense of the public interest. The game-keeper buys an unnatural abundance of fish at the expense of the public’s hawks and owls. The fish-culturist buys an unnatural abundance of fish at the expense of the public’s heron, mergansers, and terns. The forester buys an unnatural abundance of wood at the expense of the soil, and in that woods maintains an unnatural abundance of deer at the expense of all palatable shrubs and herbs.

Though beautiful and aesthetically pleasing, these goals have unintended consequences: unnatural simplicity, unnatural ecological pressures, unnatural extinctions. After this trip, Leopold made a 180-degree turn on his stance on game management. He no longer believed human manipulation of nature—especially in the effort to cultivate an overabundance of game—could last long-term. Losing predator species allows for game species to explode in number, but the overabundance causes increased pressure on plant and prey species these animals depend on. An unchecked deer population would eat palpable forest understory flora. With time, these species begin to disappear and non-palpable species dominate, creating a landscape of “unnatural simplicity and monotony.”

Be that as it may, the forest landscape is deprived of a certain exuberance which arises from a rich variety of plants fighting each other for a place in the sun. It is almost as if the geological clock has been set before that the melodies of nature are music only when played against the undertones of evolutionary history. In the German forest … one now hears only a dismal fugue out of the timeless reaches of the carboniferous.

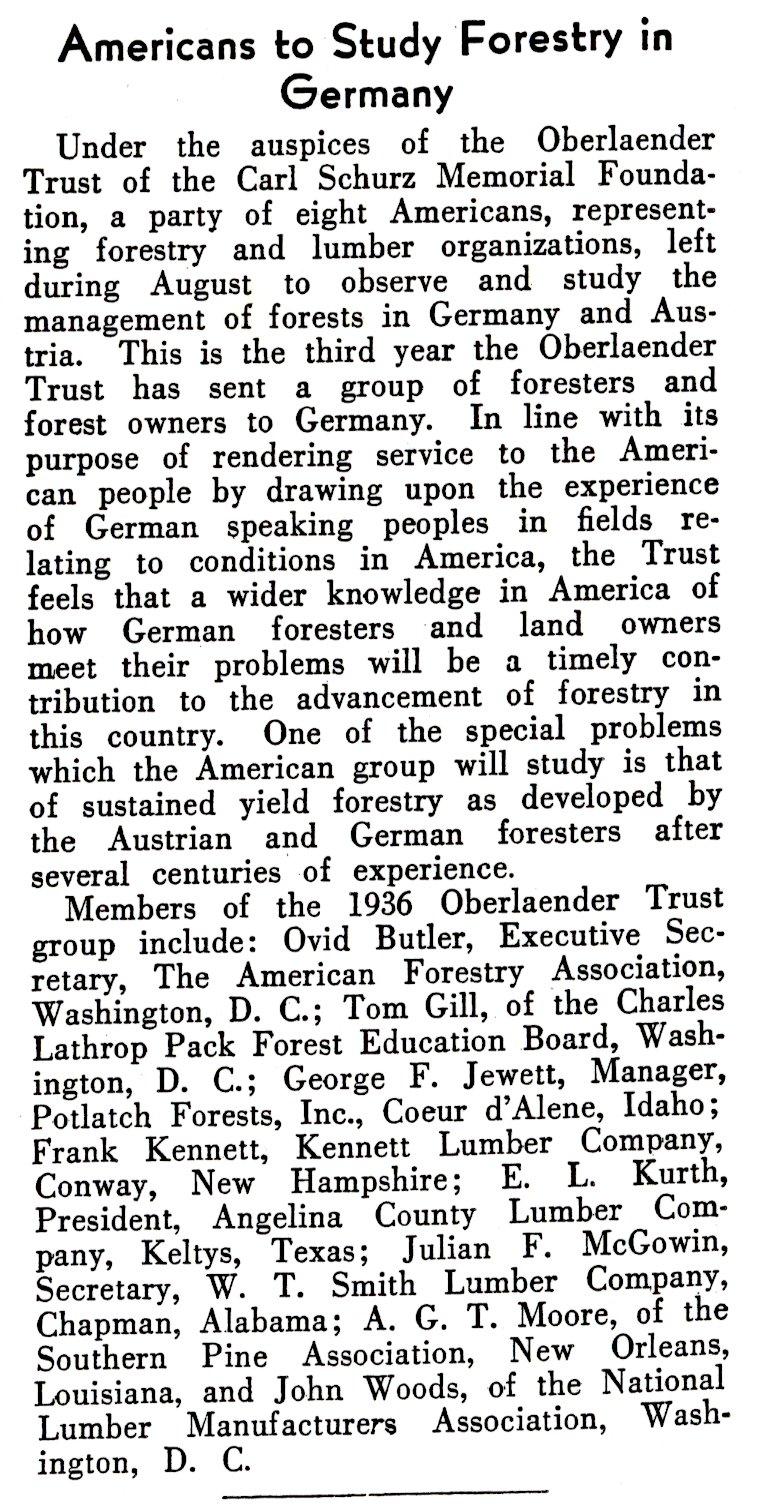

Second Foresters’ Tour (1936)

“One of the special problems to study … is that of sustained yield forestry”

The second foresters’ tour brought eight American foresters to Austrian and German forests. Two men, George F. Jewett (manager of Potlach Forests, Inc.) and Julian McGowin (secretary of W. T. Smith Lumber Company), kept detailed diaries of their journey. Both participants made extensive notes on the forests and forest practices they observed while traveling. They made frequent comparisons between American and German-Austrian methods, recording the influences of different laws, challenges, and solutions on present and future developments.

Excerpt from G. F. Jewett’s Diary

Jewett described the Kurische Nehrung, 5 kilometers from the Lithuanian border:

The method of afforestation depends upon varying conditions. Where there is a bare sand surface it is necessary to plant grass for a period of 20 to 30 years to provide a little foundation for planting trees. We saw some conifers planted on ground of this kind which were 25 years old and yet had reached a height of not more than six inches although they had spread out sideways a little. I could not believe that such little conifers could be so old, especially as they seemed reasonably thrifty and bore cones. Where there was more soil below these trees were probably a meter high. Other places where soil below existed for a long time there were fully developed trees of 20 meters in heights… While this process must be very expensive it is successful in its purpose.

Reflections from Julian McGowin’s “notes on Oberlaender Tour“

On the afforestation of sand dunes, McGowin observed: “The forest of Marchfeld is located in a plain about forty kilometers by ten kilometers which was the bed of a prehistoric lake. It is a mixture of fertile soil and sand dunes but farming has always been difficult because prevailing winds blow the sand into the fertile areas.” He continued:

In 1770 afforestation was attempted in order to hold the sand dunes and afford a shelter belt for the land in cultivation. The species selected were not suitable but in 1880 systematic afforestation was started with Black Pine. This work was carried out by the nine communes owning the land under the supervision and with assistance of the Government Forest Service… The plantations have been greatly damaged by rabbits and are now almost sixty years old and afford some revenue from timer and resin but not yet enough to pay for the maintenance cost of the forest.

In addition to his personal notes on the Oberlaender tour, McGowin recorded details about the forest systems he visited, including location, ownership, altitude, rainfall, climate, area, and tree species.

Tom Gill, secretary of the Charles Lathrop Pack Forest Education Board, took extensive photographs of the various locations and activities enjoyed by the Oberlaender Party. A selection of photographs is below:

Forestry Grants (1937)

“Through the courtesy of the Oberlaender Trust … it was possible to study recent developments there”

The final trip to Europe occurred in 1937. Seven men received funds for the study of specialized topics in forestry such as flood control, community forests, and wood utilization. They came from private industry, academia, research, and forest advocacy.

The final trip to Europe occurred in 1937. Seven men received funds for the study of specialized topics in forestry such as flood control, community forests, and wood utilization. They came from private industry, academia, research, and forest advocacy.

Dr. Nelson Brown of Syracuse University traveled to Germany mainly to study the use of wood as engine fuel in liquid or gas form, but he also investigated municipally owned forests. At the time, Brown was engaged with establishing similar community forests under the U.S. Forest Service. Upon his return, Brown published “Timber Utilization in Europe” in the December 15, 1937, edition of The Southern Lumberman, in which he compared and contrasted the American and European timber markets and summarized key findings from his expedition.

He also wrote of how creative Europeans—the Germans in particular—had become with wood utilization: “The nation is enthusiastically and actively carrying out its program of self-sufficiency” because “about one-third of its wood requirements must be imported,” he noted. In addition to developing methods for converting wood into a substitute for gas and alcohol, German researchers were integrating wood fiber into clothing to replace silk and wool—like gasoline, materials also heavily imported. To meet demand, “27 new factories [were] now being constructed in Germany for the manufacture of wood-wool and food for cattle, and swine, and many other products.” What Brown learned of was likely part of the nation’s Four Year Plan undertaken for going to war by 1940, though he probably didn’t realized it.

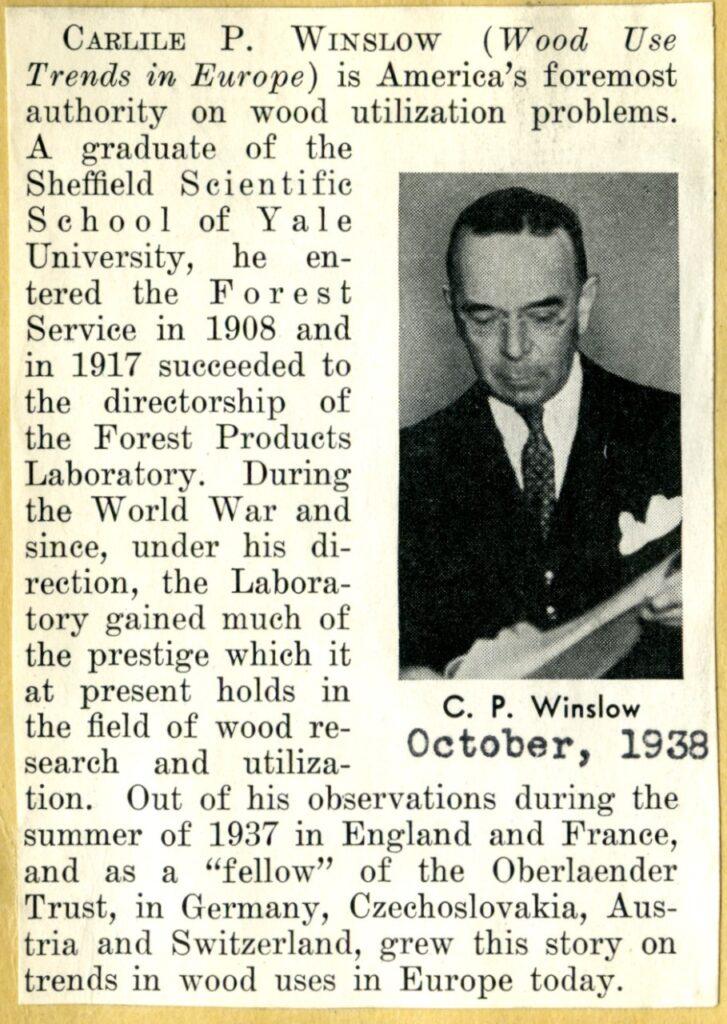

Interested in finding more efficient and new uses for wood was a major reason the Forest Service had established its Forest Products Laboratory in 1910. Carlile P. Winslow, the lab’s director, made the trip to investigate innovations in forest products. He wrote of how Europeans utilized their limited resources in “Wood Use Trends in Europe,” published in the October 1938 edition of American Forests. He summarized the timber and wood supplies situations for six European nations, five of which would soon be engulfed in war: England, France, Germany, Austria, and Czechoslovakia (the sixth was Switzerland), and compared their situations with that of the U.S.

German Forestry by Dr. Franz Heske (1938)

In 1938, the Oberlaender Trust published German Forestry, a book by Dr. Franz Heske written primarily for American foresters and private forest landowners. This book was the “outgrowth of the desire of the Trustees of The Oberlaender Trust and the members of the Carl Schurz Memorial Foundation to make the experiences of the German-speaking peoples in the field of Forestry available to the American people,” and dealt largely with forest economics and policy in Germany. W. N. Sparhawk, who had been on the 1935 Oberlaender trip and knew Heske, edited the English translation of the book.

In his preface, Henry Graves, second U.S. Forest Service chief and longtime dean of the Yale School of Forestry, explained the rationale behind the book, and by inference, as the cultural exchange program as well:

Here in America, after more than three and a half centuries of colonialization and settlement, of agricultural development and industrial expansion, it is pleasant to be referred to as a “new country.” Our pride in the imposing contributions to our national prosperity made by agriculture in cotton, wheat, in animal husbandry, and by forestry in lumber and paper, is dimmed by the realization that continued monoculture, overgrazing, and forest devastation are progressively destroying our rich soil resources. Many once-prosperous farming regions are becoming incapable of supporting their declining populations. We see the need of curbing individualistic exploitation, and we are looking toward the future with justified apprehension. In this situation we instinctively turn to the experience of older countries.

In the book, Heske touted the German government’s forest policies and promoted the conservation aspect of German forestry as a possible model for American landowners. Unbeknownst to the Americans visiting in 1935 and after, the Nazis had by then abandoned Dauerwald and its more ecologically friendly approach to forestry, and the Naturschutz (forest preservation) movement—even as they continued promoting them. By the time Leopold and the other five Forest Service men arrived, the national government was already dropping environmental measures in favor of supplying timber to its war industries.

But not everyone was taken in by what Heske was offering to America. Raphael Zon, in his book review for Science magazine, said Heske ignored the social implications that had arisen under the Nazi regime. Those included a crippling drop in wages for the head of the household who worked in the forest, and other measures, such as depriving “rural and forest workers … of almost all freedom of movement,” which left workers stuck in servitude to the landowner. Zon, a widely respected researcher who’d been with the U.S. Forest Service since 1901, caustically noted: “The bucolic paradise which Dr. Heske holds out as the ideal for us to emulate is thus nothing more than chattel slavery and feudal serfdom.” The measures taken by the Germans were “nothing but new social instruments for old ends, namely the destruction of democracy.”

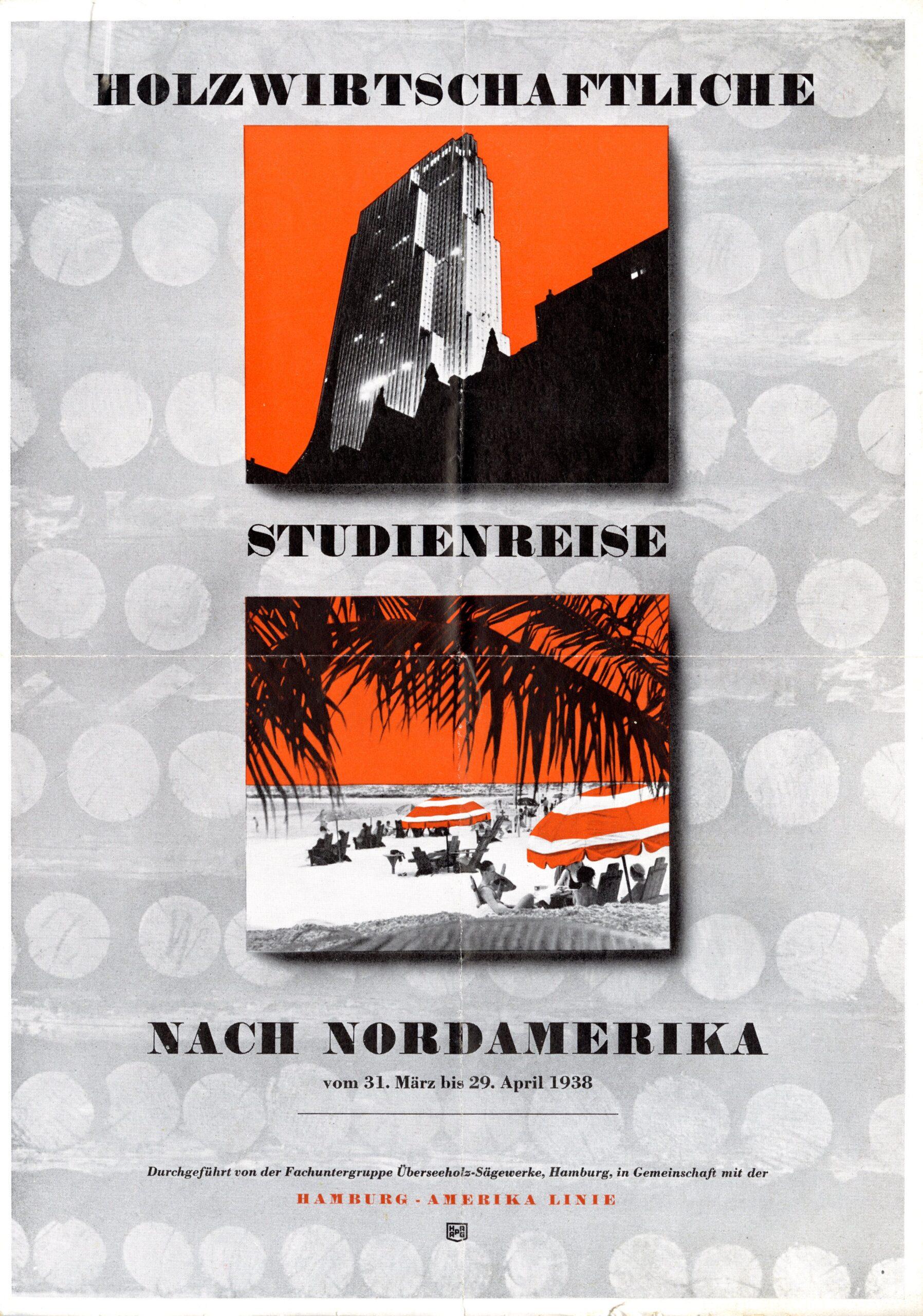

German Forestry Officials visit the United States (1938)

German advertisement for a “Wood Industry Study Trip” in North America

The exchange of forestry experts ended, according to the Carl Schurz Memorial Foundation eighth annual report, after a “tour of German forestry officials, lumber mill operators, and forestry professors through the eastern part of the United States was arranged by Der Deutsche Forstwirt [the official forestry journal of the German government] in the spring” of 1938. They arrived just a few weeks after German troops occupied Austria in March. The timing of the visit must have made for interesting—or uncomfortable—conversation at the various stops.

Twenty-eight Germans made the trip in total, with five receiving grants from the Oberlaender Trust to assist with travel expenses. They were escorted through part of the trip by the U.S. Forest Service’s Gus Lentz, who had just spent three years overseeing soil erosion control and reforestation work in the Southern Appalachian Mountains.

After sightseeing around New York City, the group toured a nearby saw mill machinery factory before heading south. Traveling by train, bus, and car, they did a whirlwind tour of lumber mills and lumber companies, and wood manufacturing plants in Virginia, the Carolinas, and Georgia before turning back north. One stop was at the Biltmore Estate in Asheville, N.C., to inspect the work done thirty years before by their fellow countryman and forester Dr. Carl Schenck. Schenck had served as estate forester from 1895 to 1909, where he operated the country’s first forestry school. At a stop in Washington, the National Lumber Manufacturers’ Association hosted a luncheon for them. From there they returned to New York, saw two more businesses, and set sail.

Companies they visited included: American Saw Mill Machinery Co. in Hackettstown, N.J.; Walker Turner Co. in Plainfield, N.J.; W. M. Ritter Lumber Co. in Bristol, Va.; Old Dominion Veneer Co. in Bristol, Va.; Lombard Iron Works and Supply Co. in Augusta, Ga.; Augusta Hardwood Co. in Waynesboro, Ga.; Hendricks Mill & Lumber Co. in Estill, S.C.; Reynolds & Manley Lumber Co., Savannah River Lumber Co., and Pierpont Manufacturing Co. in Savannah, Ga.; Reynolds Brothers Lumber Co. in Albany, Ga.; Hoffman Lumber Co. and Lexington Lumber Co. in Columbia, S.C.; Otis Astoria Corporation, R. Hoe & Co. Inc. and Ichabod T. Williams & Sons in Carteret, N.J. The group also visited a few national forests, including Pisgah and Nantahala in North Carolina, and the Coweeta Hydrological Research Station in Franklin, N.C.

Lasting Legacy of the Oberlaender Trust

With the rise of Nazism coinciding with the years the Oberlaender Trust operated the cultural exchange, the efforts to improve German-American relations likely fell short of Oberlaender’s expectations. While the Carl Schurz Memorial Foundation and the Oberlaender Trust publicly distanced themselves from the Nazi Party, criticism plagued both organizations. Due to erroneous claims that the Trust was underwriting a pro-Nazi organization in Germany called the Carl Schurz Association, to praise by Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels for the Oberlaender Trust in an October 1933 speech calling for German-American support of Nazism, and to frequent trips to the Reich by the Oberlaender family, who frequently met with Goebbels and Adolf Hitler, the public and federal government became suspicious of the Trust.

The Oberlaender family and their business partners disavowed the treatment of Jews under the Reich, but they also expressed support for some of the changes occurring in Germany. Like many conservative German elites in Europe and America, Oberlaender dismissed or downplayed excess violence as the actions of an extremist few in the Nazi Party.

Textile strikers working in Oberlaender’s hosiery company were among those who took issue with American delegates being sent to Germany to learn from their counterparts. The Federal Trades Council of Reading issued a statement in 1935, which was echoed in Raphael Zon’s criticism of German forestry policies: “Nothing learned in Nazi Germany could safely be introduced into democratic America without threatening the life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness of the working man.” In 1939, the U.S. State Department grew suspicious of the intellectual exchange and questioned whether the relationship with Nazi Germany was completely innocuous.

The American forestry men who traveled to Germany, however, stayed out of the political fray. The foresters were impressed by what they saw and learned from their German counterparts. Some returned with a hope of continuing the conversations that had started while there, and some may have hoped to adopt some of the management practices and goals. Aldo Leopold’s visit left him impressed, too. But he drew very different conclusions. For him, German forestry practices provided a cautionary warning for American forest managers. The two policies the Nazis promoted to their visitors—Dauerwald and Naturschutz—had already been abandoned by the time Leopold arrived in 1935. The “artificial,” homogenized forests he saw, and that he feared would be adopted by American foresters, continued to typify German forests on through the war.

Oberlaender died in 1936 from a heart attack, long before he could take a clear public stance against the Reich and distance the Oberlaender Trust from suspicion. His funds and mission continued to provide charitable donations to projects dedicated to public welfare, and to helping relocate German scholars to America. Among the hundreds of Americans sponsored by the Trust were Jane Addams, the settlement worker who founded the famous Hull House in Chicago, and W.E.B. Du Bois, the civil rights activist and cofounder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. The Trust also gave grants to American universities and colleges to help pay the salaries of displaced German scholars, including Albert Einstein. After the war, the Oberlaender Trust finished spending its funds as intended and dissolved in 1953.

[Foresters overlooking body of water during 1935 Oberlaender Trip to Europe].

Additional Materials

All materials, including photos and documents, for this exhibit were curated from the Forest History Society archives.

List of Grants and Awards given in Forestry (1934-1950)

The complete 1934 Wiedmann’s Heil (“Woodman’s Greeting”)

Link to full Tom Gill photo collection

“What we may learn from German forestry” by Henry S. Graves in The American-German Review

“Wilderness” draft by Aldo Leopold

“Leopold on Wilderness” by Susan Flader

George. F. Jewett’s 1936 diary from Second Foresters’ Tour

Julian McGowin’s 1936 diary and forest notes from Second Foresters’ Tour

John W. Watzek’s 1936 Letter to John Woods

Link to full Forsling photo collection

“Timber Utilization in Europe” by Nelson C. Brown in the December 1937 of The Southern Lumberman

“Wood Use Trends in Europe” by Carlile P. Winslow in the October 1938 edition of American Forests

Studienreise Nach Nordamerika 1938 German brochure advertising trip to America

1938 German-American Luncheon Speech and Attendees

USFS Service Bulletins about The Oberlaender Trust forestry trips

![[Lumberyard, Europe.] [Photo from the Clarence Forsling Papers. Photos document Forsling's 1935 trip to Europe funded by the Carl Schurz Memorial Foundation and the Oberlaender Trust.]](https://foresthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Forsling091.jpeg)