The Two Tragedies of Archie Mitchell

On this date in 1962, the Rev. Archie Mitchell was seized by the Viet Cong, bound in front of his wife and daughters, and taken away from the leprosarium where they were working near Buon Ea Na, Vietnam, never to be heard from again. This was the second wartime tragedy for Mitchell. Seventeen years earlier almost to the day, his wife was one of six people killed by a Japanese balloon bomb—the only deaths in the mainland United States caused by a Japanese attack.

Japanese fire balloon made of mulberry paper reinflated at Moffett Field, California, after it had been shot down by a Navy aircraft January 10, 1945. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

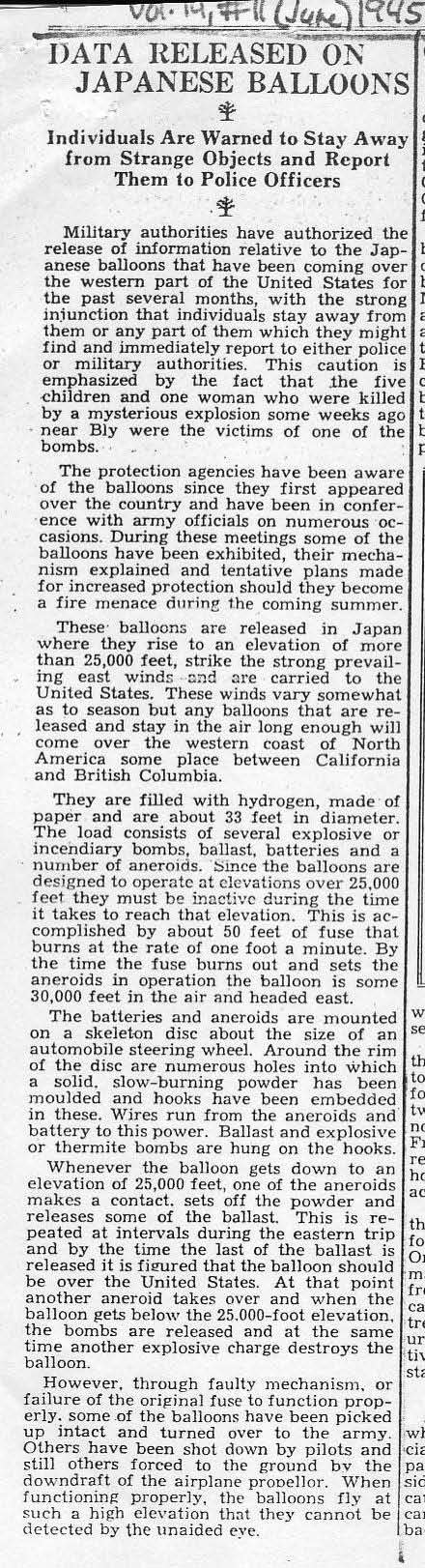

The Japanese balloon bomb program has become part of American smokejumping lore. During World War II, the Japanese sent balloons across the Pacific Ocean with incendiary bombs attached. The idea was that the devices, which typically carried four incendiary bombs and one anti-personnel bomb, would land somewhere in a wooded area, explode, and start a forest fire that would then tie up critical firefighting resources. Moreover, the threat from these devices, they hoped, would cause panic and terror to spread whether or not they started a fire. In all, more than 9,000 balloons were launched by Japan but only about 100 are known to have reached the continent, with one reportedly reaching Michigan. No fires were attributed to the bombs. And because the American press cooperated with the federal government and did not report the balloons, the Japanese never heard of any working and assumed that the program had failed.

To some extent, though, the balloon bombs had the desired effect. When the balloons first appeared in 1944, federal officials feared they might carry anthrax or other communicable diseases. The U.S. Army responded to the possibility of forest fires with Operation Firefly. As part of that program the government trained and dispatched conscientious objectors and the first all-black battalion of paratroopers, the 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion, better known as the Triple Nickles, to do battle with the aerial menace. Their training included demolition of unexploded ordinance. The Triple Nickles never fought a bomb-created fire but did participate in 36 missions and made 1,200 jumps.

It was the issue of unexploded ordnance which led to the first of Rev. Mitchell’s tragedies. On May 5, 1945, he and his wife Elsie had taken 5 children from his church to picnic and fish on land owned by the Weyerhaeuser Timber Company within the Fremont National Forest. When Mitchell reached an impasse in the road, he dropped off his passengers and proceeded to turn the car around. Elsie called out to her husband that she and the children had found something and to come see it. By coincidence a road work crew led by Richard Barnhouse, who was operating a grader, was there as well. According to Melva Bach’s History of the Fremont National Forest, from the grader Barnhouse could see the children formed in a semicircle but couldn’t see what they were looking at. Elsie called out two more times. Rev. Mitchell responded, “Wait a minute, and I’ll come and look at it.” Quoting Bach:

Just then there was a terrific explosion which shook the ground for a considerable distance. Needles, twigs, and sticks flew through the air, some of which were later picked up near the grader. Barnhouse immediately stopped the grader, which was about 150 yards from the explosion, and both he and Mitchell ran to the scene. Four of the children were dead, part of them badly mangled, another died immediately, and Mrs. Mitchell died within a few minutes. None were conscious after the explosion. Mrs. Mitchell’s clothes were on fire, and Mr. Mitchell immediately put this fire out….

When Barnhouse and Mitchell first arrived at the site, the balloon bag was stretched out full length over some low bushes with two of the shroud lines handing from a stump about ten feet in height. Parts of the mechanism and bomb were scattered quite thickly over an area ninety feet in diameter and fragments from the demolition bomb were found as much as 400 feet away. The balloon was complete and very little damaged, but it was estimated by the military authorities from its weathering, mildew on the paper, and other evidence that the balloon had been there for a month or more. [pg. 207-208]

On August 20, 1950, the Weyerhaeuser Timber Company dedicated a memorial to those killed by the bomb. In 1998 it turned the land over to the federal government to be included into the Fremont National Forest (now the Fremont-Winema National Forest). The site is now part of the Mitchell Recreation Area and is on the National Register of Historic Places. At the time of the dedication, Rev. Mitchell had been living in Asia for three years.

The plaque on Mitchell Monument reads: “Dedicated to those who died here May 5, 1945 by Japanese bomb explosion: Elsie Mitchell, age 26; Jay Gifford, age 13; Edward Engen, age 13; Dick Patzke, age 14; Joan Patzke, age 13; Sherman Shoemaker, age 11. The only place on the American continent where death resulted from enemy action during World War II.” (FHS1370)

Within two years of losing his wife, Mitchell married again and the couple moved to Asia and eventually made their way to Vietnam to serve as missionaries. They were working at a facility for treating lepers when the Viet Cong showed up on the evening of May 30, 1962. The VC seized three Americans—Dr. Eleanor Ardel Vietti, Mitchell, and Daniel Gerber, a 22-year-old volunteer—looted the facilities, harshly reprimanded the Vietnamese for working with the Americans, and disappeared with their captives. Mitchell’s wife and four children were spared only because the other three promised to fully cooperate. Betty Mitchell stayed at the leprosarium until she was taken captive in 1975, along with six other missionaries, by the Viet Cong. All were released 10 months later. Archie Mitchell, Eleanor Vietti, and Daniel Gerber are still listed among the 17 American civilians who went missing during the Vietnam War.

♦♦♦♦♦

Below are some documents from the “Japanese Fire Balloons” file found in the U.S. Forest Service History Collection. On May 31, 1945, the federal government authorized release of information about the balloons in hopes of preventing further harm to the public. The first document is an article printed in the June 1945 Forest Log, a journal published by the Oregon State Board of Forestry. It gives an excellent description of how the balloon bombs worked.

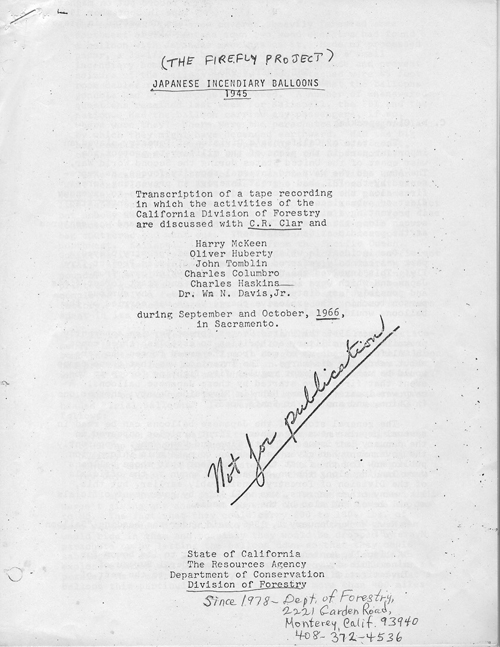

An oral history interview was conducted in 1966 about Operation Firefly. The first ten pages of this document offer a good overview of the program. Click on the image to read it.

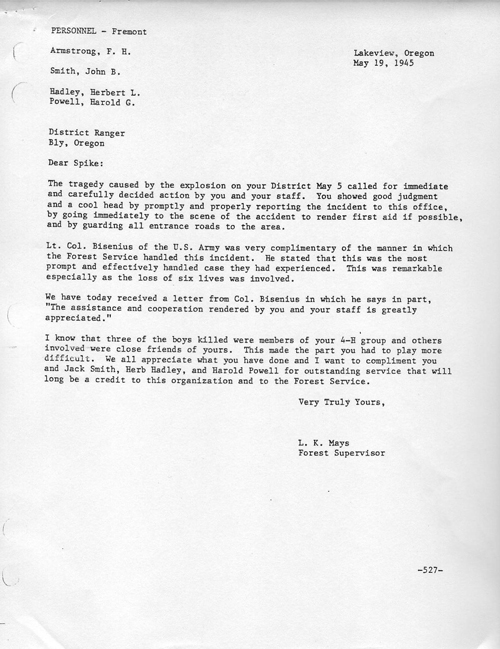

This next document is the letter sent from the forest supervisor to the district ranger about how he handled the incident.