The "Big Blowup" centennial anniversary is this weekend

Coming only five years after the U.S. Forest Service’s establishment, the devastating series of forest fires that swept over Montana, Idaho, and Washington on August 20–22 in what is known as the “Big Blowup” struck at a critical and pivotal time in the history of the young agency. Ever since the dismissal of Chief Gifford Pinchot in January 1910, his successor Henry Graves had been fighting in the halls of Congress to save the Forest Service from its political enemies. That summer, in the rugged landscape of the Northern Rockies, Forest Service rangers battled to save national forest lands from thousands of fires. The Big Blowup killed around 87 people and wiped a handful of towns off the map. The catastrophe made headlines around the world and gave the agency its first hero, Ed Pulaski.

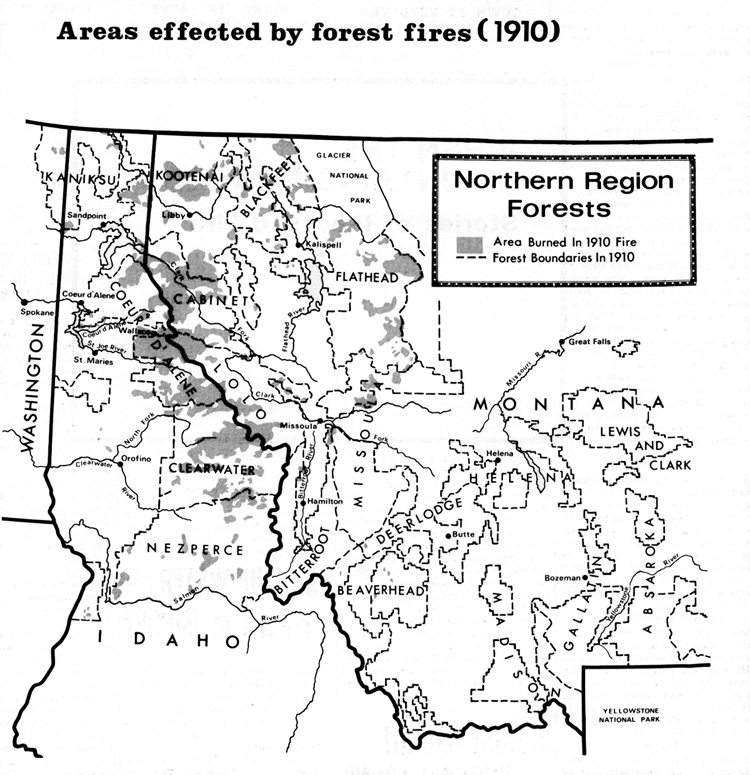

In addition to the fires seen on this map, the Forest Service was dealing with fires throughout the western U.S. when the Big Blowup occurred.

The fire incinerated 3 million acres of prime timberland in less than 48 hours. It was no small irony that a fire that very nearly annihilated the agency charged with protecting that land would instead actually save the agency. Before the fires were even out, the Forest Service moved quickly to assess the damage to the forests while at the same time salvaging its reputation. The agency and its supporters argued that the fires could have been contained and catastrophe prevented if the Forest Service had had enough men and money, and attacked their political enemies for not giving them sufficient resources to do their job. This became the agency’s mantra for the next half-century when discussing fire suppression—give us more men and money and we can conquer the enemy fire. After the Big Blowup, the agency immediately sought a cooperative approach with state and private associations to fight fire through the Weeks Act (passed in 1911) and soon launched a fire protection campaign that targeted eliminating fire from the landscape and changing how Americans viewed fire. More horrific fire seasons, especially that of 1933, led to the 10 AM policy and then the Smokey Bear campaign. The policy decision to go after fire no matter what—made even as the embers of the Big Blowup continued to smolder—continues to haunt us a century later.

You can learn all about the Big Blowup (sometimes called “The Big Burn”) and its legacy at our webpage dedicated to the 1910 Fires. You’ll find a more complete account of the fires and lots of documents relating to the incident—many written by those who fought the fires—and can learn more about the legendary Ed Pulaski too. Those wanting to understand the incident in a broader historical context will want to read Stephen Pyne’s new work, America’s Fires, published this year by the Forest History Society.

If you are in the Northern Rockies this coming weekend, you may want to take in one of the many activities going on there to mark the centennial of the Big Blowup. Missoula’s minor league baseball team will be giving away Ed Pulaski bobblehead dolls on Friday. At the Historical Ft. Missoula Museum, re-enactors from the Buffalo Soldiers National Museum will present a program on Sunday and George Sibley will screen a documentary about the fires on Monday. Wallace, ID, will host a slate of speakers including Dr. Pyne and Rocky Barker over the weekend and also a hike to the Pulaski tunnel. Below are images of the tunnel just days after the fire and this past May. The Forest Service was preparing to install “downed timber” at the restored site when our boss Steve Anderson visited the historic site then.

Mouth of tunnel where Ranger Edward Pulaski sheltered his men, photo taken September 1910

Mouth of the Pulaski tunnel, as seen in May 2010