Chapter 1: The Pioneers

"A ranger of any grade must be thoroughly sound and able-bodied, capable of enduring hardships and of performing severe labor under trying conditions. He must be able to take care of himself and his horses in regions remote from settlement and supplies."

Forest Service Use Book, 1908.

The man who sat at the roll top desk bulked large above the chair back. The black coat stretched tight in accordion pleats between his shoulders as he hunched over the desk. His shaggy black hair almost covered his stand-up white collar that peeked above the coat. And when he swung his chair around and stood up at the sound of a knock on his opened door, his over-developed paunch pushed a slight spread between his vest and trousers.

"I'm headin' back for Pecos, Mr. McClure," the man at the door said.

McClure took a half-smoked cigar from his mouth that was almost hidden by a heavy mustache. "Good," he said. "Good. And remember Fletcher, keep those reports concise . . . concise. Good-bye."

McClure gave the tails of his Prince Albert a swish, sat down and swung back to his desk to resume his writing.

This was the office of the Pecos River Forest Reserve in Santa Fe in 1900 and McClure was the new Forest Supervisor, in charge of three Rangers and an area that originally covered 300,000 acres of mountain forests, and including some of the highest peaks in New Mexico.

R. C. McClure was hardly the physical type that anyone would picture—even in 1900—as a Forest Ranger. But in those early days of the Service, when it was still part of the General Land Office of the U. S. Department of the Interior, and before Civil Service covered the appointment of Rangers, McClure was one of many political appointees who launched the infant agency.

The Pecos River Forest Reserve had been set aside by proclamation of President Benjamin Harrision in January, 1892, the very first one in the Southwest and the fourth Forest Reserve in the United States. Subsequent Presidential Proclamations established Forest Reserves that later were organized into District 3—now known as Region 3 of the United States Forest Service.*

*Originally included National Forests in Oklahoma, Arkansas, Florida, and Puerto Rico. These were transferred in 1911 and 1913, and Region 3 now comprises only the National Forests in Arizona and New Mexico and National Grasslands in New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas.

Gifford Pinchot, the idealistic conservationist who became the Chief Forester of the Department of Agriculture in 1898, had the right idea in his crusade to get "forestry from the books in to the woods." But it took awhile before there were trained Foresters to tackle the tasks—and in the meantime job-seekers who were sponsored by senators or other potent political allies moved into supervisory positions in the General Land Office's Forest Reserves Division.

McClure's employment as Forest Supervisor had been made possible by Congressional appropriation in 1898, which provided for appointment of Forest Superintendents, Forest Supervisors, and Rangers for the Forest Reserves. A resident of Kentucky, he had obtained appointment through political channels, even as had his boss, I. B. Hanna, Superintendent of Forest Reserves in the Southwest, who was from Illinois and a close friend of "Uncle Joe" Cannon, then chairman of the powerful House Appropriations Committee.

There had been two previous Superintendents for the Southwestern Region, (John D. Benedict, 1897-1899 and William B. Buntain, 1899-1900) but the new program of forest protection was slow in getting under way.

McClure's earliest reports and letters reveal that despite his lack of technical training, he was an enthusiastic and industrious supervisor, who was much concerned with seeing that the several Rangers of the Pecos Reserve put in a full day of work every day.

"We are required to make a full report of all trail work done on the Reserve, September 30, for the past quarter," he wrote Ranger Robert J. Ewing, of Glorieta, on September 23, 1900, "and as I desire to make a good showing in this line of Ranger work, I want you, in addition to your regular patrol duties, to find time this week to complete this trail (Indian Creek trail) to the top of the mountain leading to Santa Fe. I think there is about two miles of it, not a great deal of work to be done however, and I think you can do it in two days: an ax and a pick is all that you will need."

A stickler for following the book, he was frequently critical of the reports of Rangers, and as he pointed out to Ranger S. O. Fletcher, "you will follow the instructions literally, 'describe the patrol you made, the distance traveled, and the time consumed; state length of the trail cut or blazed, the time consumed and where cut.'"

Report sheets with instructions printed on the left hand margin for guidance were supplied the Rangers. When Rangers went beyond instructions, McClure was quick to call attention.

"I request that you make out a new report," he wrote Ranger Fletcher, "leaving out all allusions to weather, snow, rain, etc., so that you may get pay for that day."

And to Ranger McGlone, who was stationed in Mora County, he wrote that "the phraseology of your report for the month of December is very unsatisfactory, to say nothing of your repeated reference to trespass in the grazing of goats on the Reserve, not one of which has been made the subject of special report to this office. From the reading of your report for December (1900) the Department will doubtless conclude that your District is being overrun with goats and that you are unable to keep them off, and that therefore, the order of the Hon. Secretary of the Interior excluding goats from the Pecos River Forest Reserve, New Mexico, is not being enforced by the Forest Officers in charge of this Reserve. Such is not the case, and from my personal knowledge of existing conditions, in your District, I know that they are only grazed upon that portion of territory which, by reason of the uncertainty of the exact location of the boundary line in dispute . . ." and so on at great length, being very, very touchy about any indication that all was not well on the Reserve.

And finally, "One other criticism: December 14th, you report,—'left Cleveland P. O. (Mora County) at 9:30 a.m.' Cleveland post office is a long distance from your District, and 9:30 a.m. is very late in the morning to be starting for a day's work to be commenced after you shall have ridden half the distance required in an ordinary day's patrol."

As McClure was hardly the technically-trained forester that Gifford Pinchot envisioned as Rangers, neither were the early Rangers who served under McClure. But they were rugged outdoorsmen, ex-cowboys, ex-miners, men who loved the outdoors. They were men rugged enough to match the mountains they patrolled, and the technically-trained foresters who came later learned from them and had to match their ruggedness and stamina or they fell by the wayside.

Writing of the early years of the Forest Service in Arizona, Fred Winn* once pointed out that "the Forest Officers in the early days of the Land Office regime were a motley collection of humanity. It stood to reason that the Forest Reserves could not be administered in the field without the presence of at least some men who had an intimate knowledge of the country and were able to take care of themselves and their horses, could stand severe physical hardships, live under any conditions, prepare their own food, talk the language of the natives, and engage in combat when the occasion arose. In fact, these were men 'with bark on,' as Teddy Roosevelt was wont to describe them. Another class consisted of adventurous young men from other parts of the country who had come to the West in order to grow up with it and because they had an inherent liking for the wide open spaces."

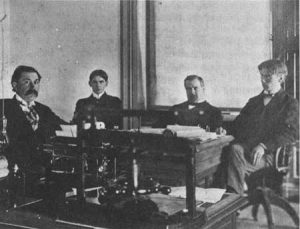

Forest Supervisor's Office, Pecos River Forest Reserve, Santa Fe, New Mexico, 1900. L to R, Supervisor McClure and third from left, I. B. Hanna, Superintendent, Southwestern Forest Reserves.

*The late Fred Winn, after his retirement from the office of Supervisor of the Coronado National Forest, started to prepare a history of the early days of the Forest Service, but unfortunately died before his writings were completed. These quotations are from some of his papers now in the Museum of the Arizona Historical Society in Tucson.

In the New Mexico Forests, Rangers of the early 1900s were "a combination ranch-and-cowboy type of men, mostly with limited education," is the way Elliott Barker, a Ranger in the early days of the Forest Service, described them. "They were rugged enough to meet any situation that we had to meet. It was that type of men, believe me, that had to lay the foundation in those rugged conditions in the early days upon which the Forest Service is building now. Without that—somebody had to do it—trained foresters could never have done it."

The technically-trained men who came later turned out to be a rugged breed, too. That is, the ones who stayed. The men who didn't have "the bark on" soon left the country for less demanding careers.

"Each year we had to take on two or three of these forestry graduates and break them in and try to teach them some of the things they don't learn in school. They had to have some basic western training to build on," Barker said.

"We had some men sent to us that were graduates in forestry that made good, and others that just did not make good. They could not grasp the western outdoor way of doing things."

Handling a horse was an important part of the business of being a Ranger, and if he could not learn to handle a horse. . . . well, it would be, as Elliott Barker put it, "the same as hiring men today who didn't know how and couldn't learn to drive an automobile."

There was need for virile men in the Service, for there was much opposition to conservation regulations, and until ranchers, timber and mining companies and residents in the Forest Districts came to an acceptance of conservation practices and Forest regulations, they sought at many opportunities to discredit the Rangers—or even to drive them off.

Forest Supervisor McClure early experienced the misery of slanderous attacks on him by a rancher whom he classified as a "common informer" of all Forest Officials "and each week sends in some slanderous report against me or some of my rangers, charging inattention, neglect, drunkenness, absence from Reserve, and other alike false reports."

In a letter to the U. S. Marshall C. M. Foraker in 1901, McClure referred to the rancher as "always an enemy of Forest Reserves, is ignorant, is a blatant free-silver Democrat and divided all Government officials into two classes, openly bad and secretly bad...."

The rancher in one letter to the Department even went so far as to claim that McClure and a Ranger got drunk and forced their way into the bedroom of a widow, who stood them off with a pistol.

In a long letter to the Commissioner of the General Land Office, McClure discussed the matter, denied all the allegations and called them "malicious and false and sent to your office by a man who would not, in my judgment, scruple to blister his soul with perjury in any court in the land. . . ." The Assistant U. S. Attorney followed it up with a letter to the Commissioner in which he stated that the Rangers and their Supervisor were "gentlemen and diligent officers."

The various complaints were investigated and within a month came a letter from the Commissioner exonerating the Supervisor and Ranger from the "slanderous charges."

While McClure and the Rangers were being plagued by the complaints of the rancher, the routine of Forest work went ahead as usual.

In his final report for the year 1900, McClure painted a bright picture of accomplishment for the new Forest Reserve.

"The Forest is in good condition, is for the most part covered with snow on the mountain tops, mesas and plateaus, while in canyons the streams are frozen over; larger streams such as the Pecos, Mora and Santa Fe are open. Cattle owned by ranchmen living in the territory near the Reserve have removed their stock to the lowlands for the balance of the winter, leaving upon the Reserve for the most part only the stock belonging to the ranchmen living inside the reservation on homesteads taken up before creation of the Reserve. Applications (for the 1901 season) relative to grazing cattle and horses will all be in by the middle of February . . .

"Rangers have been vigilant in the performance of their duties and on the alert to discover trespasses, which at this season of the year would as a rule be the cutting of timber or the taking of timber for firewood, the killing of game, etc., but not a single trespass has been discovered.

"It would seem from reading the Monthly Report of Ranger McGlone that this is a contradiction and that his District was being overrun with goats as he speaks of goats almost every other day. Such is not the case, and from personal knowledge, had by reason of a recent visit to his District, I know that there are a few bands of goats owned by Mexican ranchmen ranging in number from 25 to 200 which are grazed upon that portion of the territory in dispute as to boundary line, the settlers claiming that it is in one place, and Ranger McGlone in another, and no one knowing exactly where it is for the reason that . . . the east line . . . was never run . . . .

If McClure was bothered by only minor problems in the Pecos Reserve the same could not be said for the situation in Arizona, where the setting aside of Forest Reserves was met with mixed emotions. The Arizona Weekly Journal Miner of Prescott, discussing the new Forest Reserves in its issue of June 18, 1898, offered a friendly send-off. It reported that the Department of the Interior was formulating rules and regulations for the care of the Forests because "vast areas have been denuded by fires" and the policy of the Department "will be to preserve the Forests for the use of the people."

"The Forests will not only be preserved for use as timber but for protecting the heads of streams, holding back the snows and preventing floods," the Journal Miner said. The paper noted the importance of this feature of watershed protecting, relating that the small streams from the south side of the mountains are "the foundation of the Verde River, which is a strong feeder of the Salt River, and directly affects the Salt River Valley irrigation."

There was not quite the same acceptance of the Forest Reserves in the Williams area. There, a mass meeting was called, according to the Williams News of August 26, 1898, "to protest against the proposed setting apart of Coconino County as a reservation by the Government." The meeting proposed sending a man to Washington "who will stay there until he heads off the scheme."

The unnamed representative did not, of course, "head off the scheme," and the Williams News on September 6, 1898, reported "The Evil Deed Done," in a headline over a story that Mayor John M. Francis of Flagstaff had received a telegram announcing that the Forest Reserve regulations would go into effect on September 17, 1898. "To say the telegram was a surprise is putting it mildly. None dreamed that this almost fiendish piece of business was much more than in its infancy, and while people have been busy the past ten days getting their forces together to fight this matter in a legitimate way, here comes the startling news that the Department has already so ordered this section as a Forest Reserve. . . ."

Interior of Forest Supervisor's Office, Alamo National Forest, Alamogordo, New Mexico, March 1909.

The Interior Department's representative in the area, E. J. Holsinger, bore the brunt of the criticism with attacks that were highly personal in character.

The Williams News reported that "It's a safe 16-to-1 bet that there's one man in Arizona that—should he ever ask for bread in this section of the Territory—will be given a stone instead, and that is the United States Land Agent by the name of S. J. Holsinger . . . His actions regarding the reservation's business and his treatment of homesteaders, have, to say the least, been small, egotistical, selfish, and by no means becoming to a man in such a position. . . ."

But a couple of months later, the same paper reported that "Special Agent Holsinger visited the Prescott Forest Reserve yesterday and made the discovery that during the past winter there had been a large part of it devastated of its timber. Hundreds of mining stulls have been taken right from the Reserve, he said, despite the fact that a Forest Ranger has been employed to look after and protect it."

The same paper in June 1899, reported that "An idea of the magnitude of the forest devastation which has been going on in this section for the past few years may be had when it is known that probably no less than 25,000, and probably a greater number of these stulls have been shipped to Jerome. Each individual stull is a good sized tree."

Holsinger undertook a number of prosecutions, and on June 22, the newspapers reported that "Uncle Sam is having quite a round-up in the stull business. Special Agent Holsinger, Deputy Marshall Grindell and Forest Supervisor Thayer have been scouring the woods for the past three or four days and have placed Uncle Sam's brand on over 7,000 stulls. They estimate that they have about 5,000 more to brand."

Four civil suits involving $11,500 were filed in U. S. court and all the stulls in sight were confiscated by the U. S. Marshall. Then in July, a deposit for the full appraised value of the stulls was made, and they were released for shipment.

The man who had initiated the investigation of unauthorized timber cutting, S. J. Holsinger, was transferred to Colorado, and the Nogales Oasis saluted his transfer with these remarks:

"Call out the fence-cutters. The timber thieves in the southern part, have found that they could neither intimidate nor bluff from his duties, S. J. Holsinger, the inspector for the Interior Department, who has done more within the two years to bring before the eyes of the gentry a just fear of the law than all the men who preceded him in that position. . . ."

In eastern Arizona, a new Forest Reserve was set aside by Presidential proclamation in 1902, and Charles T. McGlone of the Pecos Reserve was transferred to the new Reserve early in 1903, with headquarters at Willcox. McGlone's early activities concerned permits for cutting cordwood, fence posts, recording mining claims and patrolling to guard against fires in the dry months of summer.

As in the Pecos Reserve, McGlone seemed especially concerned about goats grazing on the Reserve.

Writing to an applicant from El Paso who sought permission to graze goats on the Chiricahua Forest Reserve, McGlone replied that the Secretary of the Interior "upon the recommendation of this office has decided that sheep and goats will not be permitted to graze therein during the present year. The lesson of six years experience has taught us that sheep and goats are very injurious to the seedling growth of the Forest, especially so in these arid lands of the Southwest, where the protection of nature's forests is so essential in the course of natural irrigation. . . ."

In the early months of his tenure in Chiricahua, McGlone served alone, but in the summer of 1903, another man was assigned to the Chiricahua Reserve, and McGlone's letter of instructions to the new man Neil Erickson, reveals what was expected of a Ranger for the $60 a month he would be paid.

Besides reminding him to submit monthly reports, McGlone advised Erickson that "The regulations governing the equipping of Rangers for field service, and found on Page 90 of the Manual, require Rangers to provide themselves with a pocket compass, camp outfit, axe, shovel, and pick or mattock (a pick with a wide blade) . . .

"Your principal duty will be regular patrol service, which consists of riding through the Reserve to protect it from fire and trespass, posting fire warnings and notices of Reserve boundary line at all such points as line thereof may be approximately determined; you will also be expected to look after the needs and cases of free use of timber to be cut from Reserve lands and in view of this fact you are admonished to study carefully the rules pertaining to the free use of timber and stone.

"You will not be assigned to any particular District for the performance of such duties, as is customary in the larger Reserves but will maintain patrol throughout the entire Reserve at present, or until such time as another Ranger can be appointed and assigned to duty within a District or portion of the Reserve.

"The Department urges the thorough organization of field service during the present year to prevent forest fires that have been so destructive to the forest cover for the last few years, especially in this dry arid region of the Southwest, and to this end you are enjoined to be vigilant, use every means to prevent further destruction of the forest timber by this known enemy of the Forest."

About the time McGlone was shifted from Pecos to Arizona, Supervisor McClure was also due for transfer. He and George C. Langenberg changed places, and McClure went to Silver City, headquarters of the Gila River Forest Reserve. McClure, despite his several years residence in New Mexico, still dressed the part of the Kentucky colonel, with his broad-brimmed black felt hat, flowing-end black bow tie, his Prince Albert coat and gray checked trousers. His appearance so impressed A. O. Waha, a new appointee as Forest Assistant in 1905 that he could describe his appearance in detail 35 years later.