How Your Forests Are Handled

Visitors will enjoy meeting the forest ranger. He is the man on the ground, and that is where most of the business of the forests is handled. He has a district of 50,000 to 200,000 acres under his protection and management.

He marks the timber for sale, scales the logs after they are cut (fig. 12), supervises road and trail construction, builds telephone lines, cares for public camp grounds, protects the forest from trespass violations and, above all, from forest fires. He must organize his fighting crews and see that they are properly equipped with tools, food, and transportation. He must instruct and train his lookout men and guards, and keep himself on the alert and ready day and night. In case of fire, he is the commander of all fire crews in his district, and, like a general in charge of an army, directs the attack to the finish.

FIGURE 12.—Ranger scaling logs on a national forest timber sale (F—192016)

The ranger works under the general direction of the forest supervisor, who has under his care several ranger districts making up a national forest. The supervisor may also have other special assistants needed to handle certain phases of the work or unusual problems of timber growing, appraisals or survey for land purchases, or road construction.

All of the forests in the Eastern Region are under the direction of the regional forester, whose office is in Washington. He, with a corps of assistants, plans and directs the work for the region as a whole. In Washington also is the central office of the Forest Service, the Forester's office, from which all the work of the service throughout the Nation is directed.

A town without trees is cheerless,

A country without trees is hopeless.

Controlling the Red Enemy

Foremost in the hearts and minds of the forest officers is the task of saving the forest—the mature timber, the young trees, the trees of tomorrow—from destruction by forest fires. Fire has always been the arch enemy of the forest, and until the general public is sufficiently aroused from its apathy to realize the enormous damage resulting yearly from forest fires, the task of fire control will remain one of large proportions. Undaunted by the seeming public disregard, the Forest Service has made and is making rapid progress in fireproofing the national forests. The number of fires and fire damages are gradually decreasing.

Fire prevention is the most important part of fire control. Nearly all the fires in the Eastern Region are man-caused—most of them thoughtlessly caused—and therefore preventable. Here the task is to so awaken the public consciousness to fire danger and damage that the tourist, the camper, the hunter, the fisherman, the lumberman, the farmer with his brush fire—in fact, all, who for any reason are in or near the forests—will exercise the same degree of caution with matches, smokes, and fires as they would in a powder or gasoline storage house.

Federal laws and the laws of various States provide penalties for carelessly or willfully setting fire to the forests. Any information which might lead to an arrest and conviction in such a case will be adequately rewarded not only in money but in the satisfaction of helping to protect the public property.

Burned forests pay no wages, build no homes.

Everybody Loses When Timber Burns

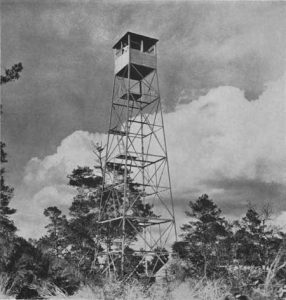

Careful preparations are made by forest officers to detect and suppress forest fires that get started in spite of efforts to prevent them. In the national forests of the East and South 77 lookout towers, 13 lookout houses, and nearly 3,000 miles of telephone lines have been built. The towers are located on high peaks where large areas of forest lands are in view, and the telephone lines connect these observatories with the rangers, fire guards, and suppression crews. The lookout man, trained in the details of the fire-suppression organization with which he is in contact, lives in quarters right at the tower (fig. 13) and is on the alert every dry day and often far into the night to detect at the moment of its first appearance any wisp of smoke—the indication of a potentially disastrous fire.

FIGURE 13.—The lookout man scans the horizon for signs of fire (F—225024)

His telephone immediately communicates information on signs of fire to the ranger, fireguards, and trained suppression forces, who are dispatched without delay to the point of danger. They go equipped with tools, food, and supplies (fig. 14) to enable them to stay until the enemy is conquered and every spark, each a potential cause of renewed disaster, has given up its last breath of heat. So far as possible, they go in automobiles and motor trucks. Often the fires are far beyond the end of the motor road, and the fire fighters must walk over trails, or perhaps miles through trackless forests to reach the blazes. Miles of roads and trails, constructed each year in all of the eastern and southern national forests, are making more and more of these remote areas accessible by rapid transportation. Many more miles are needed, and the work is going ahead as fast as funds are provided.

FIGURE 14.—Trained fire crew ready for battle with forest fire (F—221529)

Could the public fully realize that all this effort and expense is necessary because of human carelessness or maliciousness, it would go far toward making every person careful with fire in the woods and turning the hand of society against the criminal who deliberately fires the forest.

Other Enemies Need Watching

Tracking down and destroying the horde of insects and tree diseases that battle for supremacy in the forests is less spectacular than fighting forest fires, but it is a very necessary and important activity. Whole pine forests have been destroyed by the bark beetle. Chestnut blight, an incurable disease of the chestnut, has destroyed practically all of this species. An effort is being made to dispose of large quantities of blight-killed chestnut in the forests of the southern Appalachians. In the Northeastern States the white-pine blister rust threatens one of America's historic and most valuable tree species. Fortunately this disease can be controlled by the eradication of an alternate host, the various currant and gooseberry bushes. A far-flung battle line of determined and scientifically trained men has met this pest at its front line. It will be controlled.