Mt. Mitchell, Where Mystery, Intrigue, and Forest History Meet!

At this time of year the mountains of North Carolina are a great place to go view the leaves changing colors. One popular destination is Mt. Mitchell, the highest peak east of the Rocky Mountains, found just off the Blue Ridge Parkway at mile marker #355. You may be familiar with the name Mt. Mitchell because of the Weeks Act. The Mt. Mitchell Purchase Unit was among the first ones organized under the 1911 law. But do you know how the mountain came to be named? It’s a story steeped in intrigue and mystery.

Born in Connecticut in 1793, Elisha Mitchell graduated from Yale College in 1813 and taught for a few years in the North before coming to the University of North Carolina in 1818 to teach mathematics and natural philosophy. In 1825 he added chemistry, geology, and mineralogy courses to his repertoire. That same year he also took over and completed the geological survey of North Carolina. In all, he taught for 39 years. In 1821, Mitchell was ordained as a minister and combined “preaching with his education and scientific interests for the rest of his life.” The University of Alabama awarded him an honorary doctor of divinity degree in 1838, which explains the “D.D.” on the memorial plaque.

The following description of how the mountain came to be named for him and why he’s buried atop it comes from the University of North Carolina’s “Documenting the South” website. You can also learn more in Timothy Silver’s book, Mount Mitchell and the Black Mountains: An Environmental History of the Highest Peaks in Eastern America (UNC Press 2003), another source consulted for this post.

“Mitchell is best known for his measurement of the Black Mountain in the Blue Ridge and his claim that one of its peaks was the highest point in the United States east of the Rocky Mountains. He first noted in 1828, in the diary he kept while working on the geological survey, that he believed the Black Mountain to be the highest peak in the area. In 1835 and again in 1838 he measured the mountain, showing the highest peak to be higher than Mount Washington in New Hampshire’s White Mountains. In 1844 he returned with improved instruments and measured the highest peak at 6,708 feet, 250 feet higher than Mount Washington. By that time local people were referring to the peak as Mount Mitchell. However, Mitchell’s claim was challenged in 1855, when [Congressman] Thomas Clingman [a former student of Mitchell’s], arguing that Mitchell had measured the wrong peak, insisted that the one [Clingman] had climbed and measured stood at 6,941 feet. As a result of the ensuing controversy, Mitchell returned to the Black Mountains in 1857 in a final attempt to prove Clingman wrong and justify his own previous measurements. On 27 June, leaving his son and guides, he started out alone, was caught in a thunderstorm, and apparently fell down a waterfall and drowned in the pool below.”

Despite Mitchell’s efforts to prove that he had found the tallest peak east of the Rockies—which is how he came to be in the mountains and meet his death—the mystery of who first climbed it and made that measurement have never been conclusively resolved. Clingman’s claim that in 1855 it was he, and not Mitchell, who had first measured the peak fell victim to the outpouring of sympathy for Mitchell following the beloved and respected professor’s death. The argument, which had been playing out in the popular press at the time of Mitchell’s death, then turned even nastier when some of Clingman’s political opponents called him a murderer even though he wasn’t there and Mitchell’s death was ruled an accident. With Clingman’s personal and political reputation damaged beyond hope, he dropped the matter. Mitchell’s defenders nevertheless continued gathering “evidence” and sworn statements that seemingly proved that he had discovered the mountain on his first trip in 1835 (subsequent trips in 1838 and 1844 had not resulted in accurate measurements either). The removal of Mitchell’s body from its original burial site in Asheville to the top of Mt. Mitchell on June 16, 1858, which was done at the insistence of his supporters, cemented the professor’s claim in the public’s mind. That he was later entombed there simply made the cementing of opinion literal. Today Mitchell is remembered as a “hero and martyr,” while Clingman is “a back-biting scoundrel.”

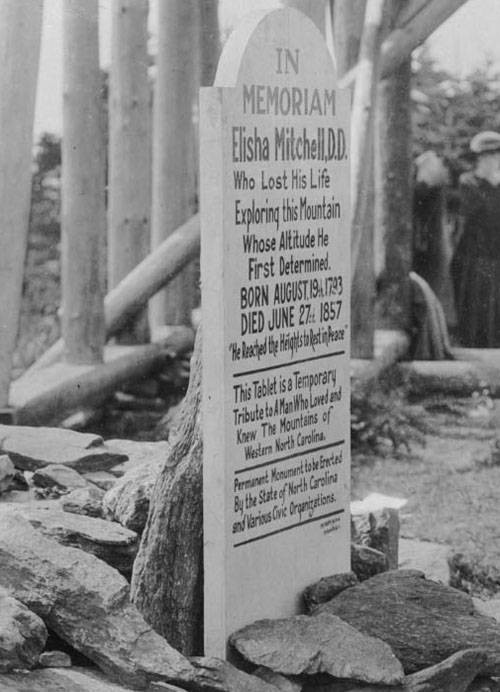

On September 28, 1928—seventy years after his remains had been reinterred on the mountain that bore his name—a permanent memorial plaque was dedicated to Elisha Mitchell at the peak of Mt. Mitchell. FHS has photos of both the temporary and permanent grave markers installed in the 1920s. The original wooden lookout tower, built in 1916 and visible in the second image below, was replaced in 1926 by a stone tower, part of which can be seen in pictures further down. That tower was replaced in 1959, and that one was replaced in 2009 with a handicap-accessible observation deck (at bottom). Today the grave and overlook are in Mt. Mitchell State Park. The photos are from our North Carolina Forest Service Photograph Collection.

This temporary tablet marking Elisha Mitchell’s gravesite was installed in 1922.

Josephus Daniels at Dr. Mitchell’s grave, with the temporary tablet, in 1922. Note the wooden lookout tower in background. In 1916, at the time Mt. Mitchell State Park was established, the state built a covered wooden platform about 15 feet high. That was replaced in 1926 with a stone tower designed in a medieval motif.

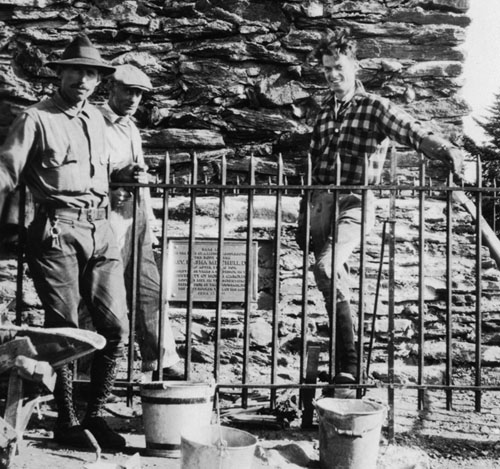

Harold M. Sebring, R.G. Wheaton, and W.C. McCormick at the temporary tablet, circa 1926.

Prior to the permanent memorial marker for Mitchell being installed, a stone lookout tower was constructed at the summit in 1926. Photo taken April 1927.

Here’s the grave of Dr. Elisha Mitchell before it received its permanent tablet. Two of the women identified are tourists: Miss Margaret Turner, of Oteen, North Carolina, and Miss Edna Ritenour, of Fairfax, Virginia. Photographed on June 13, 1927.

Elisha Mitchell’s tablet.

The original setting of Elisha Mitchell’s tablet.

Workers take a break while installing the permanent tablet at the grave of Elisha Mitchell, 1928. No, that’s not Harry Connick Jr on the right.

Mitchell’s grave at the summit of Mt. Mitchell, 1928.

Elisha Mitchell’s refurbished grave with the same memorial plaque, at the new observation tower, built in 2009 (photo by twbuckner).