Happy 125th Birthday, Aldo Leopold!

On this date in 1887, author, forester, ecologist, and conservationist Aldo Leopold was born in Burlington, Iowa. The founder of the science of wildlife management and a major influence on the wilderness movement, wildlife preservation, and environmental ethics, he is perhaps best known for his book, A Sand County Almanac (1949). In honor of his birthday, we’ve asked filmmaker Steve Dunsky to share his thoughts about the subject of his latest documentary film.

As one of the filmmakers of Green Fire: Aldo Leopold and A Land Ethic for Our Time, I was asked for my reflections on the occasion of Aldo Leopold’s birthday. January 11, 2012, marks the 125th anniversary of his birth. When he died suddenly in 1948, he was only 61 years old. He has been dead now for more years than he was alive.

A film about a person who died more than six decades ago runs the risk of being irrelevant. Particularly if that person is a conservationist and scientist; our planet, and our understanding of it, have changed so dramatically in the past half century. But Leopold’s ideas are so enduring, so far ahead of his time, that we find his story resonates with audiences across the United States, and in the seventeen other countries where the film has screened to date.

Green Fire has clearly struck a chord. More than 1,000 people turned up to the world premiere last February. Since then, screenings, both large and small, have been held in libraries, schools, nature centers, and independent theaters. We have seen audiences of 600 on college campuses, despite a distribution and marketing effort that is purely a grass roots effort and by word-of-mouth.

Green Fire has clearly struck a chord. More than 1,000 people turned up to the world premiere last February. Since then, screenings, both large and small, have been held in libraries, schools, nature centers, and independent theaters. We have seen audiences of 600 on college campuses, despite a distribution and marketing effort that is purely a grass roots effort and by word-of-mouth.

Making Leopold’s story relevant today was a major focus of our film team. My wife Ann and I, along with our Forest Service colleague Dave Steinke, directed and produced the film. With our partners the Aldo Leopold Foundation and the Center for Humans and Nature, we set out to tell both the story of Leopold’s life and his contemporary legacy.

Leopold biographer Curt Meine, the film’s narrator/guide, weaves together Leopold’s biography with the stories of people who are living Leopold’s land ethic today—from ranchers in New Mexico to environmental educators in Chicago. As the voice of Leopold, narrator Peter Coyote brings Leopold’s wonderful language to life.

In the film, NOAA administrator Jane Lubchenco says that Leopold’s land ethic (she calls it an “Earth ethic”) is more relevant today than it has ever been. As I write this, I am attending the Waimea Ocean Film Festival in Hawaii, where Green Fire has screened four times. It is so easy to make the connection to oceans because the land ethic is a universal concept.

Leopold’s legacy also includes the cutting-edge conservation disciplines of today: protecting biodiversity, restoring damaged ecosystems, growing healthy local food. Leopold’s concept of land health speaks directly to current notions of healthy ecosystems and their connection to healthy communities. Everyone gets it.

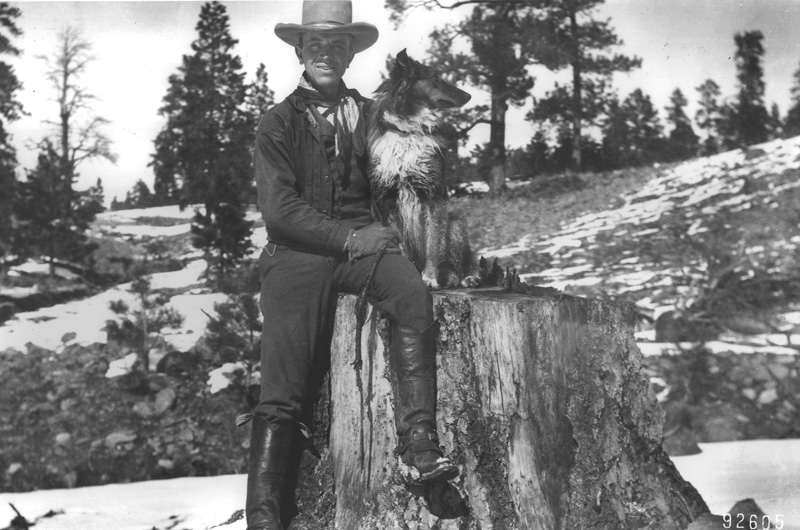

Aldo Leopold and “Flip” on the Apache National Forest in Arizona, 1911. (FHS4408)

One of the questions we often hear following our screenings is: What did you learn about Leopold during the making of this film?

Leopold said: “There are two things that interest me: The relation of people to each other and the relation of people to land.” When audiences ask me what I learned about Leopold in making the film, I often tell them that he strikes me as a profoundly well-adjusted individual. He related well with people, despite being an outdoorsman and writer, two occupations often done in isolation. He loved his wife and children, and they clearly loved him. He was very close with his parents, but not in a suffocating way. His students worshipped him, his professional colleagues admired him. He could talk with scientists and farmers, hunters and engineers, ranchers and wilderness advocates. As an amateur environmental historian, I have found these qualities to be somewhat rare in the conservation field; but without those relationships, conservation will never succeed.

Leopold is also relevant to us today because he allows us to move beyond the intractable ideological debates and look at the deeper ecological and economic relationships. He wants us to look not at the things that divide us, but at the things that connect us: water, food, energy.

As with so many others, Leopold has had a profound personal influence on me and my wife. Ann and I have worked for the U.S. Forest Service for more than twenty years. We came to the agency in the late 1980s at a moment of crisis and, in hindsight, a huge paradigm shift—the end of the “big timber” era. As the timber program “hit the wall,” Forest Service Chief Dale Robertson invoked Aldo Leopold as he outlined the transition from the utilitarian wise-use model of Gifford Pinchot to the “new perspective” of ecosystem management. No large organization, particularly a government agency, changes quickly. Indeed it has taken two decades for the staffing, structure, and targets to catch up with new philosophy. But where we work, in California, the top priority of the region is ecosystem restoration. The priorities are healthy, resilient ecosystems, conserving biodiversity, and sustaining local economies—all very Leopoldian, all very encouraging.

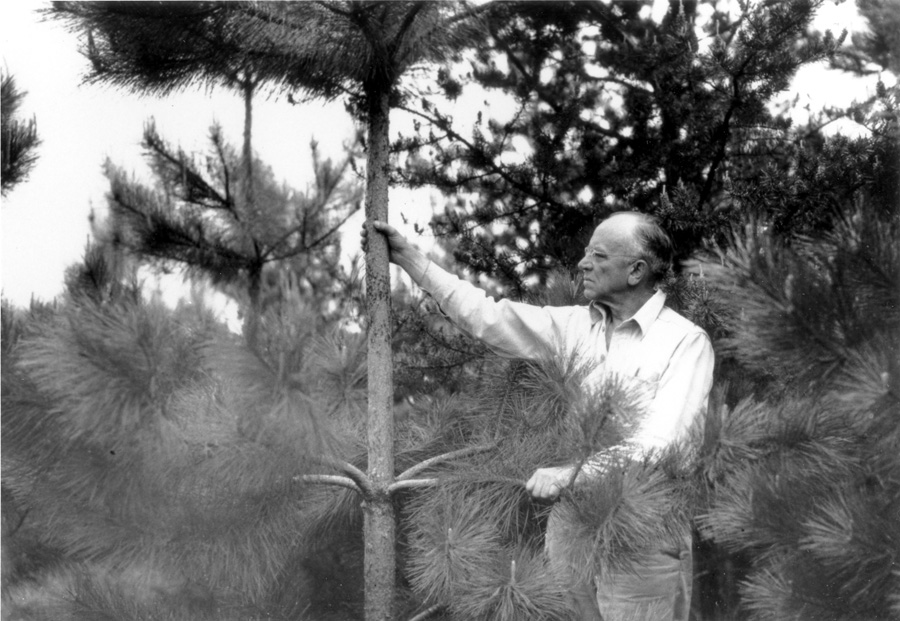

Aldo Leopold with a young pine tree. (FHS4402)

Leopold has shaped our personal goals as well. We are fortunate to have inherited a farm property in New England. Leopold is always on our minds as we think about what we will do with it. Leopold said that “conservation will ultimately come down to rewarding the private landowner who conserves the public interest.”

Whether or not we will be rewarded, we understand it is in our best interested to be good “biotic citizens.” And so we will try to take the lessons from Leopold (and his children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren) and see what we can do to make the land and our community healthier, more resilient, and more sustainable.

Leopold is such an appealing figure because everyone can take something useful from his life and his legacy, and that is why his popularity continues to grow. As we move into his 125th year, his “green fire” continues to burn as brightly ever.

###

Steve Dunsky is co-director, writer, and producer of The Greatest Good: A Forest Service Centennial Film and Butterflies and Bulldozers: David Schooley, Fred Smith and the Fight for San Bruno Mountain.For more information about Green Fire, visit: www.greenfiremovie.com.

For additional information about Aldo Leopold, visit the Aldo Foundation: www.aldoleopold.org.

To learn more about the Forest Service’s work on ecological restoration, visit: http://www.fs.fed.us/restoration/QandAs.shtml

To view our photo gallery of Aldo Leopold, visit: https://foresthistory.org/envira/aldo-leopold/