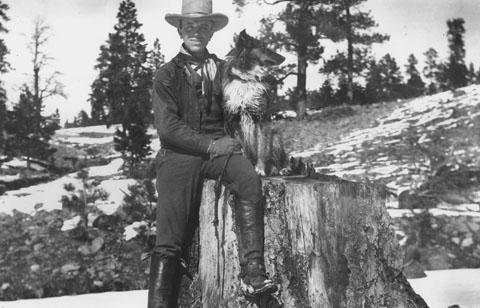

Reigniting the Green Fire: Aldo Leopold Story Comes to Life

Curt Meine reflects on the long journey that brought about the making of the new documentary film Green Fire: Aldo Leopold and a Land Ethic for Our Time. Curt worked with Steve Dunsky, Ann Dunsky, and Dave Steinke–the folks who brought you The Greatest Good documentary–on this project.

After five years of talking, imagining, brain-storming, fund-raising, partnering, writing, road-tripping, filming, re-writing, recording, editing, test-screening, re-re-writing, re-recording, re-editing—and occasionally eating and breathing and sleeping—the first full-length documentary film on the life and legacy of conservationist Aldo Leopold is now showing at a theater near you. (Or perhaps at a library, visitors center, classroom, or film festival.) Green Fire: Aldo Leopold and a Land Ethic for Our Time premiered in early February at the National Hispanic Cultural Center in Albuquerque, and since then in Wisconsin, California, Iowa, and Washington D.C. Some 200 other local screenings are scheduled over the coming months in communities across the country and beyond. It has been shown in Sweden and Mexico, with Croatia, India, Turkey, Japan, Brazil, Canada, and other countries on the horizon. It will have its first screening before an academic audience this weekend, at the 2011 meeting of the American Society for Environmental History in Phoenix. All of this in response to a film that was only completed two and a half months ago.

In 1988 I published Aldo Leopold: His Life and Work, the first full biography of Leopold. In researching that work, I became fully aware of the pent-up interest in Leopold, and the fact that there was a built-in audience for his story. The pressure was on, not to get published—the normal challenge aspiring writers face—but to not blow the opportunity. Fortunately, the richness of Leopold’s experience, thinking, and archival legacy carried the work forward. Similarly with Green Fire, the film production team felt confident that there was a strong existing core of interest in Leopold’s story and the land ethic; the challenge was to communicate the broader significance of that story in a compelling and coherent way.

In our early editorial meetings, we debated at length the basic questions: Who is our audience? What is the main message of the film? How can we most effectively illustrate and share that message? What important themes and episodes from Leopold’s life and work should we try to show? We found ourselves hung up on an essential dilemma: Do we want to create a historical documentary that will tell Leopold’s fascinating life story, or are we more interested in contemporary expressions of his ideas and influence? It might have been easier to go down either one of those paths, but instead we chose to pursue both: to weave the historical and contemporary together. To do that most effectively, the producers decided they needed an on-screen narrator and guide to make the necessary connections. Thus was I kidnapped, taken out of the role of comfortable project advisor, and put in front of the camera.

I suppose I would have put up a greater fight on this matter if I hadn’t seen that I would be sharing the anxiety, and the opportunity, with others. Back in 1988 I thought that I had made my contribution with the biography, and that I was done with Aldo Leopold. I can now see, in retrospect, that I was only beginning—that my own work as a conservationist would continually draw upon history and Leopold’s story; that in the course of that work, I would constantly cross paths with people who are continually adding new meaning, content, and direction to the land ethic. Leopold himself saw the land ethic as an expression, not of any one individual, but of a “thinking community.” In making the film, we were able to draw upon diverse members of that community—conservation biologists and urban educators, students and historians, farmers and ranchers. In rolling out the film, we have evidently been able to tap into that large community.

That community is hardly of one mind. As I write this, emails are pinging in on my laptop, bearing comments about the film from our latest screening. One correspondent has weighed in with praise for the film, but also with concern that we did not confront directly or forcefully enough the political reality surrounding climate change and other critical global conservation issues. Another correspondent has commented from the opposite side, expressing thanks that the filmmakers decided not to make a more political “message” film, which would have driven her away, but rather gave her a new entry point through which to make vital connections. Our community is evidently ready to have meaningful conversations and to engage in effective action.

Conservation, a friend of mine has taken to saying, is not merely a set of policies or programs; conservation is a journey. So it was for Leopold. He provided a focal point, a summary of his own experience, in “The Land Ethic.” As we all make our journeys, we compare notes and share insights, bemoan losses and forge connections. We write essays… and we even make movies. Along the way, we in the “thinking community” continue to elaborate and explore the land ethic. The early response to the film encourages us to believe that another phase of exploration is just beginning.

Curt Meine is director for conservation biology and history at the Center for Humans and Nature, senior fellow with the Aldo Leopold Foundation, and research associate with the International Crane Foundation. His books include Aldo Leopold: His Life and Work (reissued in a new edition in 2010), Correction Lines: Essays on Land, Leopold, and Conservation (2004), and The Essential Aldo Leopold: Quotations and Commentaries (1999). Green Fire is a joint production of the Aldo Leopold Foundation, the Center for Humans and Nature, and the U.S. Forest Service.

Curt Meine is director for conservation biology and history at the Center for Humans and Nature, senior fellow with the Aldo Leopold Foundation, and research associate with the International Crane Foundation. His books include Aldo Leopold: His Life and Work (reissued in a new edition in 2010), Correction Lines: Essays on Land, Leopold, and Conservation (2004), and The Essential Aldo Leopold: Quotations and Commentaries (1999). Green Fire is a joint production of the Aldo Leopold Foundation, the Center for Humans and Nature, and the U.S. Forest Service.

Information on the film can be found at www.greenfiremovie.com.