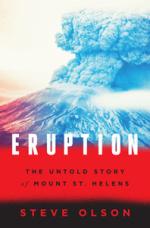

Explosive Truths: A Review of the book Eruption: The Untold Story of Mount St. Helens

The vial measures about 1.75″ in length but contains a great deal of information and memory.

This is an expanded version of the review of Eruption: The Untold Story of Mount St. Helens, by Steve Olson, which first appeared in the April-May 2017 issue of American Scientist.

When I visit environmental history–related locations, I typically bring back two reminders of the trip: photographs I’ve taken and rocks I’ve collected from the sites. When I returned from a trip to Wallace, Idaho, in 2009—a small, picturesque town located in the state’s panhandle and surrounded by national forests—I came home with rocks and a small vial of volcanic ash from Mount St. Helens.

The rocks came from outside the abandoned mine where, in 1910, Forest Service ranger Ed Pulaski and his men rode out one of the most famous wildfires in American history. Known as “the Big Burn,” the conflagration consumed 3 million acres in about 36 hours. Burning embers and ash fell upon Wallace, and fire consumed about half the town. The fire transformed the U.S. Forest Service, then only five years old; the lessons agency leadership drew from it—that more men, money, and material could prevent and possibly remove fire from the landscape—eventually became policy. The agency’s decision to fight and extinguish all wildfires, known as the “10 a.m. policy,” is one America is still dealing with because of the ecological impact removing fire from the landscape for half a century has had.

Seventy years later, another famous natural disaster coated the town in ash when Mount St. Helens, which sits in the middle of the Gifford Pinchot National Forest in southeastern Washington, erupted, sending some of its content miles into the air and drifting east towards Wallace and beyond. The vial I brought back contains some of that ash. The tiny container is a reminder that this disaster, too, transformed the Forest Service. It also transformed the U.S. Geological Survey.

The transformation began on March 20, 1980. After 123 years of dormancy, Mount St. Helens woke up. Seismometers had detected a 4.0 earthquake about a mile below the surface of the volcano, which is located in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest in southwestern Washington. In the days immediately following, more quakes were recorded, as many as 40 an hour. These weren’t aftershocks—it was a volcanic swarm. Business owners, loggers, and the media demanded to know when the volcano was going to blow. As Seattle-based journalist Steve Olson discusses in his book Eruption: The Untold Story of Mount St. Helens (W.W. Norton, 2016), there was no easy answer: The science wasn’t there yet. But as Olson demonstrates, the lack of clear scientific guidance and an absence of straightforward jurisdictional relationships fostered government inaction at all levels, with disastrous results. Given recent seismic activity around Mount St. Helens (earthquake swarms were recorded in June and November of 2016, although these gave no indication of imminent danger), revisiting the events of 1980 seems especially timely.

The transformation began on March 20, 1980. After 123 years of dormancy, Mount St. Helens woke up. Seismometers had detected a 4.0 earthquake about a mile below the surface of the volcano, which is located in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest in southwestern Washington. In the days immediately following, more quakes were recorded, as many as 40 an hour. These weren’t aftershocks—it was a volcanic swarm. Business owners, loggers, and the media demanded to know when the volcano was going to blow. As Seattle-based journalist Steve Olson discusses in his book Eruption: The Untold Story of Mount St. Helens (W.W. Norton, 2016), there was no easy answer: The science wasn’t there yet. But as Olson demonstrates, the lack of clear scientific guidance and an absence of straightforward jurisdictional relationships fostered government inaction at all levels, with disastrous results. Given recent seismic activity around Mount St. Helens (earthquake swarms were recorded in June and November of 2016, although these gave no indication of imminent danger), revisiting the events of 1980 seems especially timely.

Just after the March 20th quake, some immediate protective measures were taken. The Weyerhaeuser Company, which was harvesting some of the last old-growth timber on its land surrounding Mount St. Helens on land it had owned since 1900, evacuated its 300 employees, and the Washington Department of Emergency Services advised everyone within 15 miles of the volcano to leave the area. But within a week, restlessness set in. After all, livelihoods were at stake. Area law enforcement couldn’t keep U.S. Forest Service roads closed to the public indefinitely and, given Weyerhaeuser’s economic and political influence in the region, public safety officials dared not close roads on its land. Beyond that, law enforcement simply didn’t have the resources to staff all the roads that snaked their way through the forest and around the volcano and nearby Spirit Lake.

On March 26, state and local officials, along with U.S. Forest Service personnel, the media, and a Weyerhaeuser representative, gathered in a conference room for a scientific briefing. The presenter, U.S. Geological Survey geologist Donal Mullineaux, along with his colleague Dwight Crandell, had spent two decades studying Mount St. Helens, publishing their findings in a 1978 report titled Potential Hazards from Future Eruptions of Mount St. Helens Volcano. Based on this work, the two were later considered founders of the field of volcanic hazard analysis. To the assembled group, Mullineaux reported that for the past thousand years, Mount St. Helens had erupted about once a century—most recently in 1857. Several eruptions had been violent lateral explosions, he noted, which had deposited white pumice as far as six miles away. He went on to describe possible characteristics of a future eruption: The area could be decimated without much warning by pyroclastic flows—powerful air currents of searing gas and pulverized rock capable of traveling at speeds in the hundreds of miles per hour. A landslide could hit the Swift Reservoir, about 10 miles to the south, and trigger a flood. Mudflows might sweep through the river valleys. And although lateral explosions were not well understood at the time, it was possible that another one could occur, blasting massive amounts of rock from the mountaintop directly into adjacent valleys. The next eruption was coming, the geologists had concluded in the report, “perhaps even before the end of this century.”

Dumbfounded by the direness of the warning and the imprecision of the timeline, a state official asked, “You mean to tell us that we as a nation can send a man to the Moon and you can’t predict if a volcano will erupt or not?” That was indeed the case. Mullineaux’s job was to convey the facts based on the geologic history. What to do with the information—whether to reopen roads to the public, for example, or to allow people to return to their homes and jobs—was up to the politicians and emergency planners.

Decisions about how and whether to restrict public access to the area quickly became political. In mid-April, the Forest Service designated two hazard zones. The red zone took in mostly Forest Service land to the north and east of the mountain. Its access was limited to scientists and law enforcement officials. However, an exception was made for lodge owner and newly minted folk hero and media darling Harry Randall Truman, who had lived beside the volcano for 54 years and strenuously defended his right to continue doing so. Refusing to leave, Truman remained in the red zone—no one had the political will to remove him. He even had the support and encouragement of the governor to stay. The blue zone extended to the southwest of the red zone; there, loggers and property owners could come and go during the daytime if they had permission. To the west and northwest of these zones sat prime Weyerhaeuser timberland. The Forest Service had no intention of restricting the lumber company’s property and alienating the powerful employer.

Washington Governor Dixie Lee Ray, a former biology professor who had improbably won the governor’s mansion in 1976 during the post-Watergate political backlash, had final say over the zones’ boundaries. Ray’s contrarian, acerbic personality—she delighted in insulting the press and encouraged Truman to stay despite the wishes of local officials—and her friendship with George Weyerhaeuser, president of the lumber company, made it unlikely that she would extend the blue zone’s boundaries into Weyerhaeuser land, as geologists and law enforcement wanted. The request to expand the blue zone sat on her desk unsigned the morning of May 18, when Mount St. Helens exploded and killed 57 people.

The real strength of Olson’s book lies in his handling of what happened after May 18. Before that, this reader was frustrated by his thirty-page digression into 100 years of history of the Weyerhaeuser family and company just to tell us that in 1980, after that initial earthquake alarmed his loggers and made them reluctant to go back to work, George Weyerhaeuser was not a man who’d change his mind after making a decision, and that decision was to keep logging. Olson follows this later with a chapter-length biography of Gifford Pinchot, the first Forest Service chief, that ends with a brief but essential discussion of the Forest Service’s multiple-use policies that came into play in the 1970s.

These digressions weaken and slow the book’s narrative. It feels like padding. He takes too long to get back to 1980, especially since his stated reason for writing the book was hearing of reports indicating that nearly all of the 57 victims of the eruption had flouted the law. The reports kindled in Olson a long-standing desire to understand why so many people had been so close to an active volcano.

The explanation that Governor Ray and others offered almost immediately afterward, a myth that still persists, was that nearly all were there illegally, having skirted around roadblocks and ignored warnings. Yet Olson found that of the 57 dead—who included campers and hikers, Weyerhaeuser loggers, sightseers, and people monitoring the volcano, such as geologist David Johnston—only Truman lacked permission to be there. In fact, most of the victims were outside the existing blue zone, even as the request to expand it sat on Ray’s desk. Had the disaster happened on a weekday, Olson notes, hundreds of Weyerhaeuser loggers could have been killed in the blue zone (which they had permission to enter during the daytime). None would have been there illegally.

The idea that the victims are to blame for their own deaths, Olson writes, “is the product of a carefully fabricated lie” invented and perpetuated by Ray and other public officials, who were “unwilling to take any blame for the disaster.” They claimed the victims had been warned and shouldn’t have been where they were. Ray stuck firmly to her story, and soon what might today be characterized as an “alternative fact” became, after much retelling, accepted as truth.

Olson’s anger about this prevarication is justified, and his book builds a solid case for condemning the politicians for their handling of the situation. However, those interested in digging further into the details of the actual cataclysm—scientific, personal, political, and otherwise—will find Richard Waitt’s 2014 title, In the Path of Destruction: Eyewitness Chronicles of Mount St. Helens, an invaluable and sobering read. Waitt, a volcanologist who analyzed ashfalls at Mount St. Helens in the weeks before its eruption, spent 30 years collecting accounts from hundreds of eyewitnesses, including survivors, scientists, rescue and recovery teams, and law enforcement. He rightly believed that these accounts could prove vital to researchers. He also combed through media archives to find the words of the victims themselves, and these make clear how little the public understood about possible hazards in May 1980.

Finally, Olson discusses the impact of the eruption on the scientific community. Those who had been working at the site were devastated. “Despite all their efforts at monitoring the volcano,” Olson notes, “they were unable to provide any warning of its eruption.” He concludes that:

perhaps the greatest failure of the monitoring effort at Mount St. Helens was the insufficient attention devoted to the worst things that could happen. . . . A large event was possible but unlikely, and scientists still have difficulty dealing with low-probability high-consequence events. But without some knowledge of what could happen, the people around the volcano that Sunday morning were unprepared for what did happen.

The U.S. Geological Survey made significant procedural changes in the wake of the cataclysm. Having gained a better appreciation of the demands of conveying scientific knowledge outside scientific circles, the USGS established a new role in its ranks: Information scientists—experts knowledgeable about the data and experienced in media relations—would disseminate information to the press and the public. The agency also developed preparedness plans for hazardous volcanoes and created a standardized volcanic activity alert-notification system, which it modeled after the National Weather Service’s alert system for tornadoes and hurricanes. Its volcanologists also pressed on with renewed vigor. As a result, researchers’ understanding of volcanoes and lateral blasts has increased greatly because of Mount St. Helens—a consequence that should benefit many whenever the mountain rouses again.

Ominous clouds hang over the area of devastation from pyroclasitc flow in Coldwater Creek drainage/Green River area. Trees at left were untouched by the fast-moving blast on May 18. (USDA Forest Service – American Forestry Association Photo Collection)

Initially eager to get back to business as usual—which meant supporting the timber industry—the Forest Service ultimately saw the eruption as an opportunity for supporting scientific study. It seemed that before the ash had evened settled, debates over whether to conduct salvage timber operations and replant or instead turn the national forest lands around the volcano into living laboratory erupted with fury not unlike that shown by Mount St. Helens. With the unemployment rate in the surrounding area at 33 percent, local officials and business leaders favored logging, but scientists wanted to leave it alone to see what happened. Olson quotes a professor of zoology from Ohio State University as saying, “We have no site on the earth, apart from Mount St. Helens, where we can test some of these ideas of ours. We have needed beautifully clear, bare sterile land, and from this eloquent explosion, which no government on earth is wealthy enough to achieve for us, we have it virtually for free.”

The Forest Service initially estimated losses from the eruption at $134 million, which included an estimated one billion board feet of timber as well as infrastructure like bridges and buildings. Some 62,000 acres of its land suffered damage; 89,400 acres of state and private lands were affected as well. Though Olson correctly faults the Forest Service for being slow to accept the idea of setting aside enough acreage as a laboratory to truly be useful, he misses an opportunity to discuss what the agency ultimately did do in any detail—listen to its scientists and enable the study of how nature reacted to the event.

Jerry Franklin, Ecological Basis for Management of Northwest Coniferous Forests project leader, takes a close look at riparian vegetation returning along Coldwater Creek on St. Helens Ranger District in the Mount St. Helens Geological Area (USDA Forest Service – American Forestry Association Photo Collection)

His chapter “The Scientists” focuses on the impact experience by geologists and geology detailed above. In the chapter after that, titled “The Conservationists,” in less than three pages Olson skims over what “scientists” and “researchers”—no affiliation is given for these nameless figures—found under the pumice and what emerged from it. (The rest of the chapter actually has little to say about conservationists; instead it talks about what it’s like to visit the national monument.) The Forest Service’s decision to monitor instead of log allowed researchers including Jerry Franklin and James A. MacMahon the opportunity to study the massive disturbed area, much as the unnamed zoologist envisioned. They and others greatly increased their understanding of ecological processes in disturbed areas. This work led to a reexamination of traditional forestry practices, which ultimately contributed to the development of ecosystem forest management over the next decade. The land transformed by volcanic ash transformed the land management agency. That’s what I’m reminded of when I look at that vial of ash.