Reclaiming Maxville: The Legacy of African Americans in a Lumber Town

Tweet ShareWith generous support from the MillsDavis Foundation, FHS partnered with the Maxville Heritage Interpretive Center to develop and share this story of forest history. This exhibit was curated by Yolanda Hester and Elizabeth Flowers of Frameworks and Narratives, LLC, with advisement from Gwendolyn Trice and Sierra Newby-Smith of the Maxville Heritage Interpretive Center. The project was overseen by FHS Librarian Lauren Bissonette with help from FHS Historian James Lewis.

Introduction

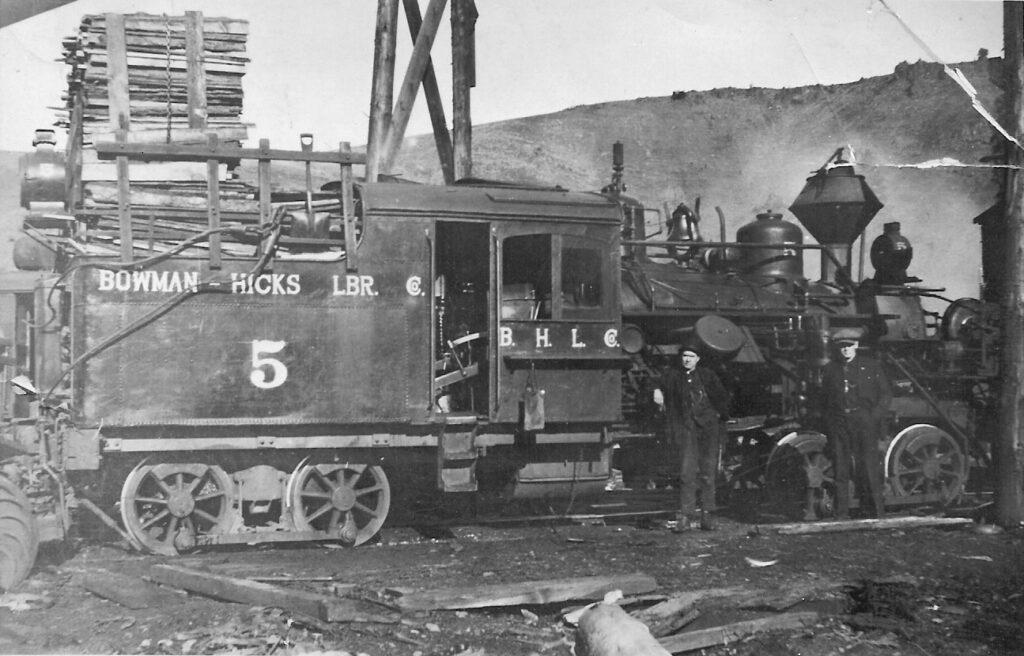

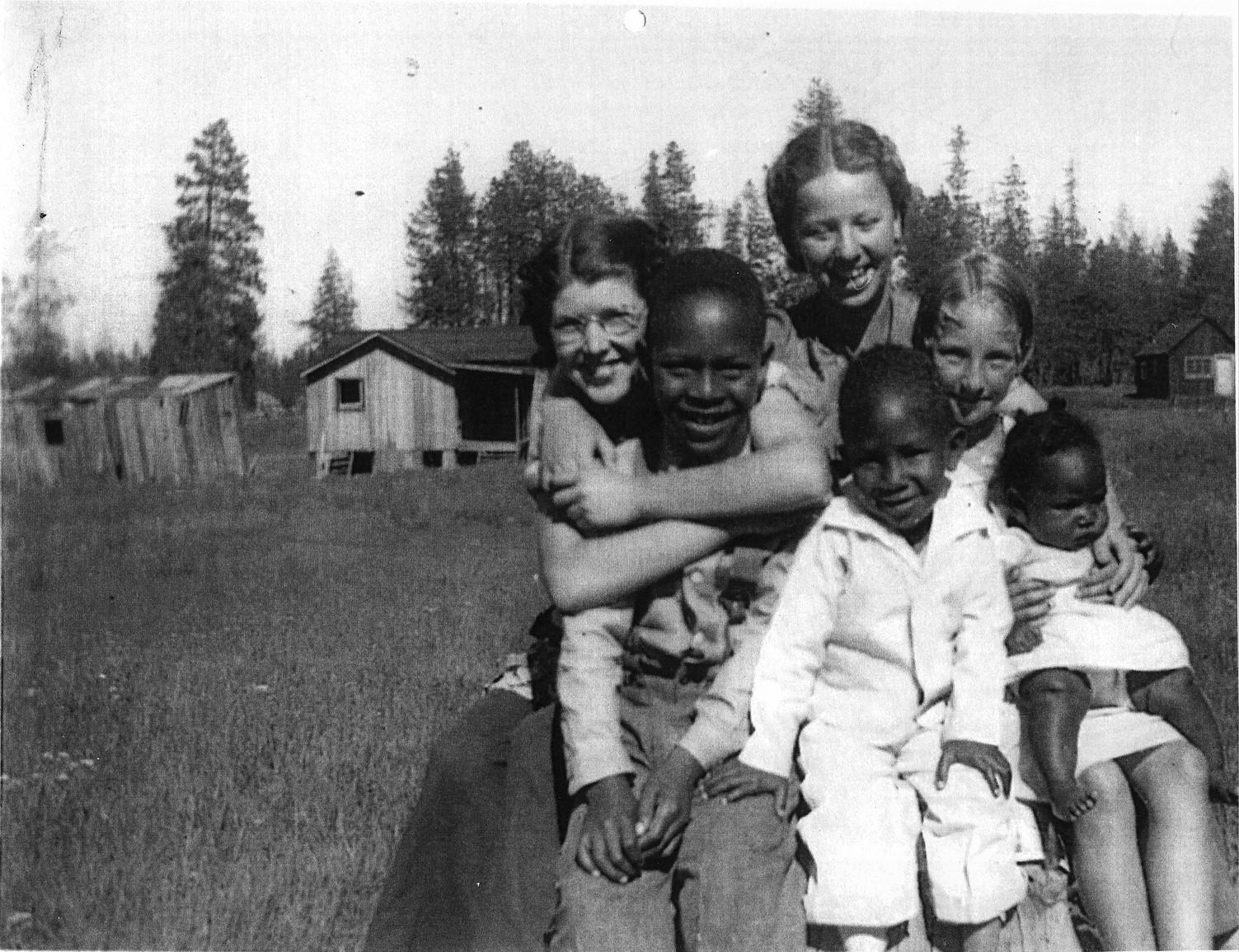

In 1923, the Bowman-Hicks Lumber Company of Kansas City, Missouri, moved west to the vast, lush forests of rural northeast Oregon. It initially purchased sawmills in La Grande and Wallowa but would soon set its sights on a remote area of Wallowa County to build its headquarters and lumber camp. Maxville would grow to roughly 400 residents, becoming one of the largest towns in the region. And despite Oregon Exclusion laws that prevented African Americans from settling in the state, Maxville would attract both Black and White lumber workers, who together would navigate the intricacies of segregation to form an interracial community. In 1933, devastated by the Great Depression and changing trends in the lumber industry, the company town and mill closed, and by the late 1940s the last remaining residents left. In recent years, descendants of Maxville residents have worked to reclaim their history through oral histories, preservation of photos and artifacts, and bringing descendants and their families together for annual celebrations.

Contents

The Land of the Nez Perce

Bowman Hicks Comes to Oregon

Building Maxville

Recruiting Workers

Working in Lumber

Degrees of Freedom in an Interracial Town

Maxville Closes

Reclaiming The History: Maxville Today

Additional Resources

The Land of The Nez Perce

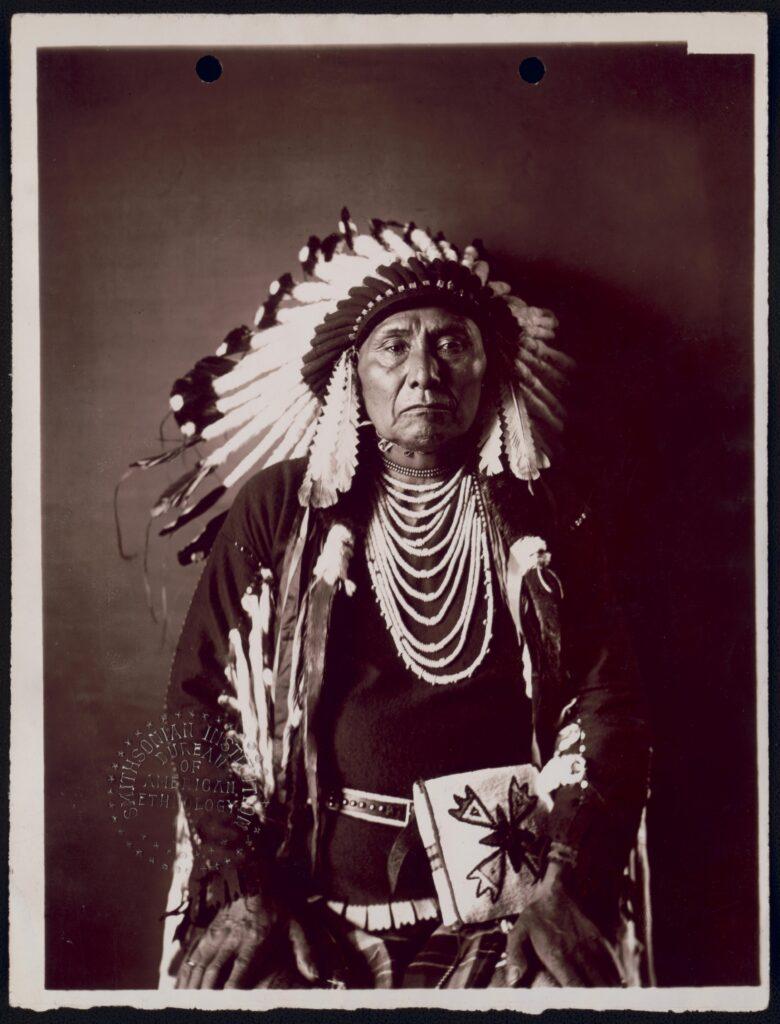

“The Earth was created by the assistance of the sun, and it should be left as it was. The country was made with no lines of demarcation, and it’s no man’s business to divide it.” —Chief Joseph

For thousands of years the Pacific Northwest has been inhabited by a multitude of indigenous groups. Roughly 60 tribes lived, in what is now Oregon, in balance with the natural resources of the land. The Nimíipuu (or the “original people”) inhabited the eastern portion of the Great Basin that divides the Cascade and Bitterroot mountains in present-day southeastern Washington, northeastern Oregon, and north-central Idaho. The Nimíipuu would later be known as the Nez Perce, or “pierced nose,” a name given to them by French fur traders despite the practice never being a part of their tribal customs. The name still holds today.

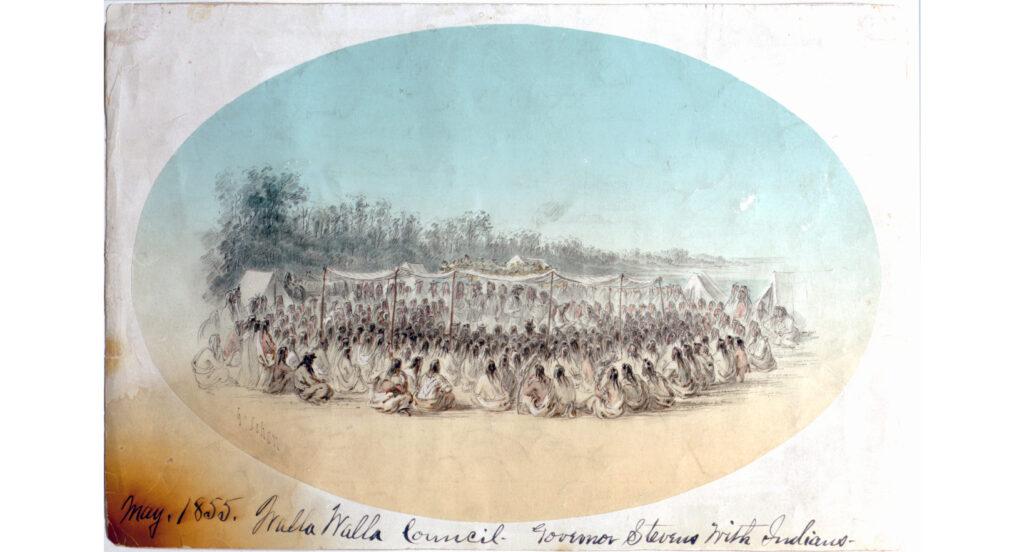

The Walla Walla Council, where sovereign tribal nations met with the US. Courtesy of the Washington State Historical Society.

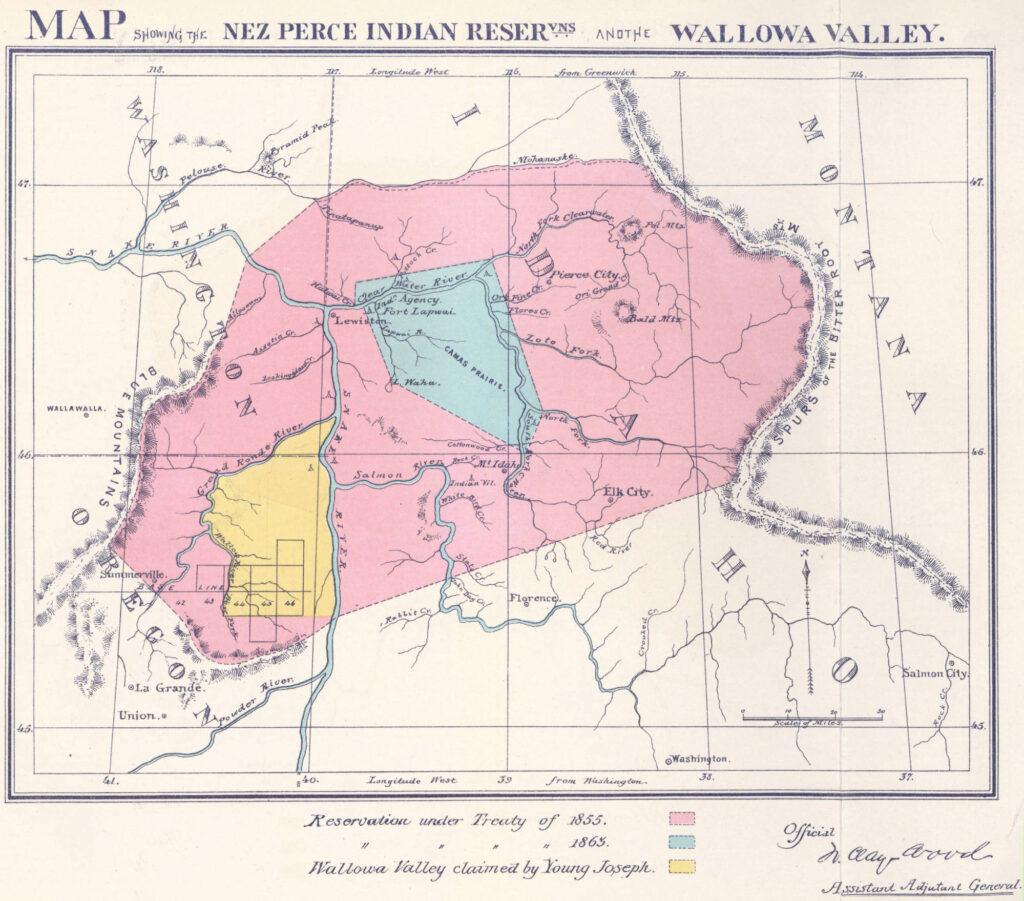

The Nez Perce Indian Reservations and the Wallowa Valley (1876), courtesy of Washington State University Libraries.

The first European explorers to the Oregon coast arrived in the 1500s. The earliest well-documented extended stay by United States citizens was the Lewis and Clark Expedition, which arrived in 1805. In 1811, the first American-owned settlement was established at Fort Astoria, a fur-trading post located at the mouth of the Columbia River that was sold two years later to a Canadian firm. These sparse encounters would prove mutually beneficial for both local tribes and European settlers, offering opportunities for trade and exchange.

Although the discovery of gold, timber, and other natural resources brought increasing numbers of settlers to the region, it was the Donation Land Claim Act of 1850 and subsequent treaties that would have the greatest impact on the dispossession of lands from Indigenous people. The United States Congress passed the Donation Land Claim Act to promote homesteading in the Oregon Territory to White or partial Indigenous (mixed with white) settlers. However, it discriminated against nonwhite persons. It was one of the most generous land acts, offering 320 acres to unmarried White men and 640 to married couples, fueling unprecedented settlement in the area.

Hin-mah-too-yah-lat-kekt, also known as Chief Joseph, Nez Percé chief, in traditional dress, 1900. Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division.

The act generated more than 7,000 land claims, totaling about 2.6 million acres, causing tensions to flare between indigenous tribes and the new arrivals. The Treaty of 1855 and the Treaty of 1863 (or the “Thief Treaty,” according to the Nez Perce) would further exacerbate the conflict by removing Nez Perce bands from their ancestral lands and relegate them to reservations, only to then reduce the reservation size by 90 percent.

Chief Joseph, the hereditary leader of the Wallowa Band of Nez Perce, resisted the forced removal. Tensions between non-treaty Nez Perce groups, settlers, and the United States government led to The War of 1877. In October of that year, Chief Joseph surrendered and was taken by military escort first to Fort Keogh in Montana and then to the Coville Reservation in northeast Washington. By 1885, the remaining Nez Perce were split up and sent to both the Coville Reservation and the Lapawi Reservation in Perce County, Idaho. It would not be until 1899 that Chief Joseph and some of his followers would finally see their homeland of Wallowa again, but only for a visit. When inquiring about purchasing land, no one would sell to him, and White settlers argued that they did not want Chief Joseph or his people in Wallowa. In 1904, Chief Joseph died in exile on the Coville Reservation.

Bowman-Hicks Comes to Oregon

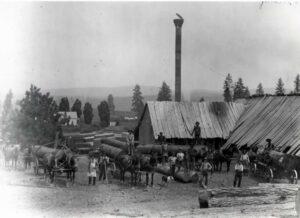

By the time of Chief Joseph’s death, the land of the Nez Perce was occupied by settlers, industrialists, speculators, immigrants, and migrants. The expansion of railway lines in the 1880s made the territory more accessible and attractive. It also made lumbering possible and profitable. The early lumber industry in Oregon was dominated by small, seasonal mills, but that changed by the close of the nineteenth century. With the forests of the Northeast, Midwest, and the South largely cut out by then, the untouched reserves of lush ponderosa pine, Douglas-fir and western larch of the Pacific Northwest attracted timbermen from those regions.

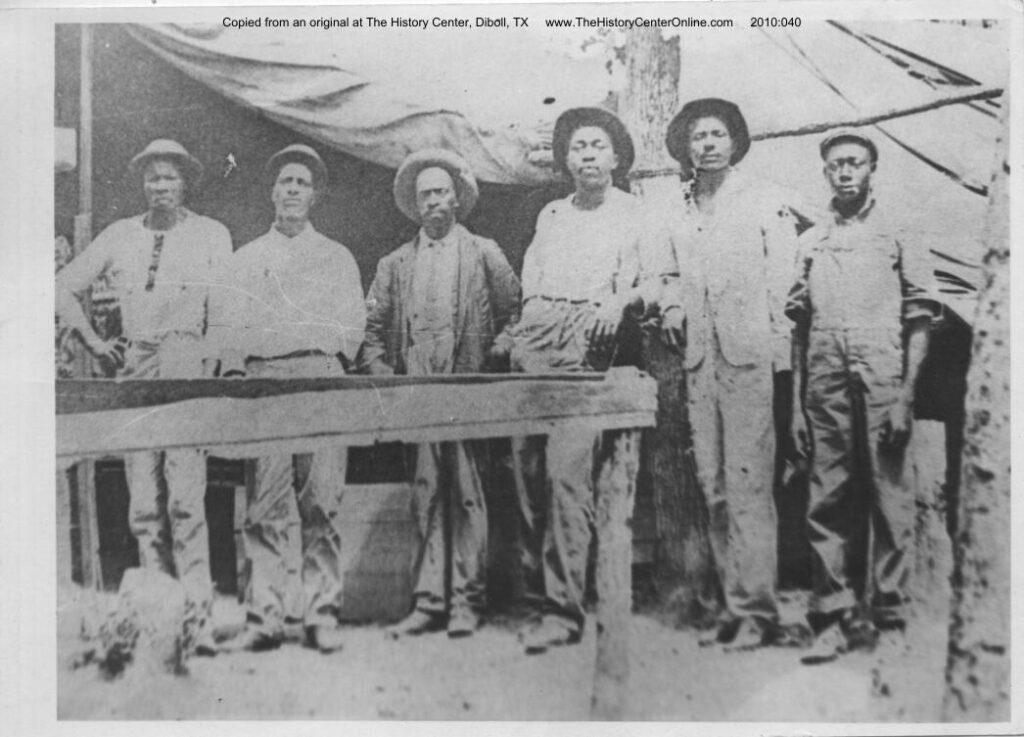

The Bowman-Hicks Lumber Company was established in 1900 in Kansas City, Missouri, by S. H. Bowman, C. R. Hicks, and B. C. Bowman. Soon after, they purchased a lumber camp in Loring, Louisiana, as the diminishing of timber reserves pushed the industry southward. A significant portion of the Loring labor force were African American. However in keeping with the laws and culture of Jim Crow, employees lived in a segregated company town, with separate schools, churches, and living quarters. As timber reserves declined through the 1910s, Bowman-Hicks looked to expand its operations to Oregon.

In 1923, Bowman-Hicks Lumber Company purchased land and two lumber mills in northeast Oregon: an estimated 23,000 acres from the Nibley-Mimnaugh Co. in Wallow and a reported 100,000 acres from the George Palmer Lumber Company in La Grande. Soon after they scouted for land to build a company town. Located thirty miles north of Wallowa, remote Bishop Meadows offered level ground, ideal for expanding train tracks, and a stream for a water source. The company purchased the land to build their company town and western headquarters. The town was named Maxville, rumored to be named after the company’s superintendent, J. D. MacMillan. Irene Barlow, whose family lived in the area, recalled:

“The Maxville area had homesteaders. . . Quite often the husband would have 160 acres and the wife would have 160 acres so they would end up with 320 acres but is wasn’t too productive and they really were having a hard time making a living. So when the Bowman-Hicks Company moved into the area and wanted to buy their land, the homesteaders were happy to do that. Then they went to work in the town of Maxville for Bowman and Hicks logging company and it worked out well for both individuals.”

—Irene Barklow, MHIC Oral History

Building Maxville

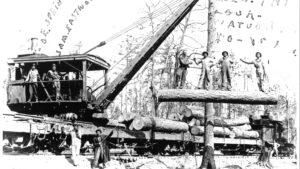

Chester Gorbett and his son Rolin Gorbett were the contractors who built the trestles and the headquarters lodge at Maxville. This photo is of a railroad trestle under construction. This rail line was built into the north woods to haul timber to the mill at Wallowa. This line was only used for a short time beginning in 1922 until the late 1920s. The last of the rails were removed and sold for scrap iron in 1933. Courtesy of Wallowa History Center.

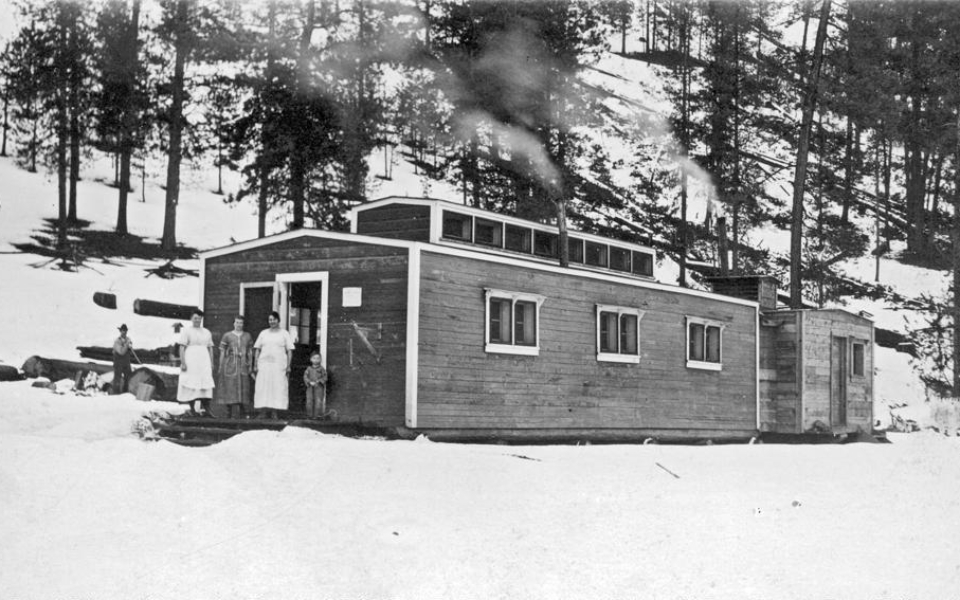

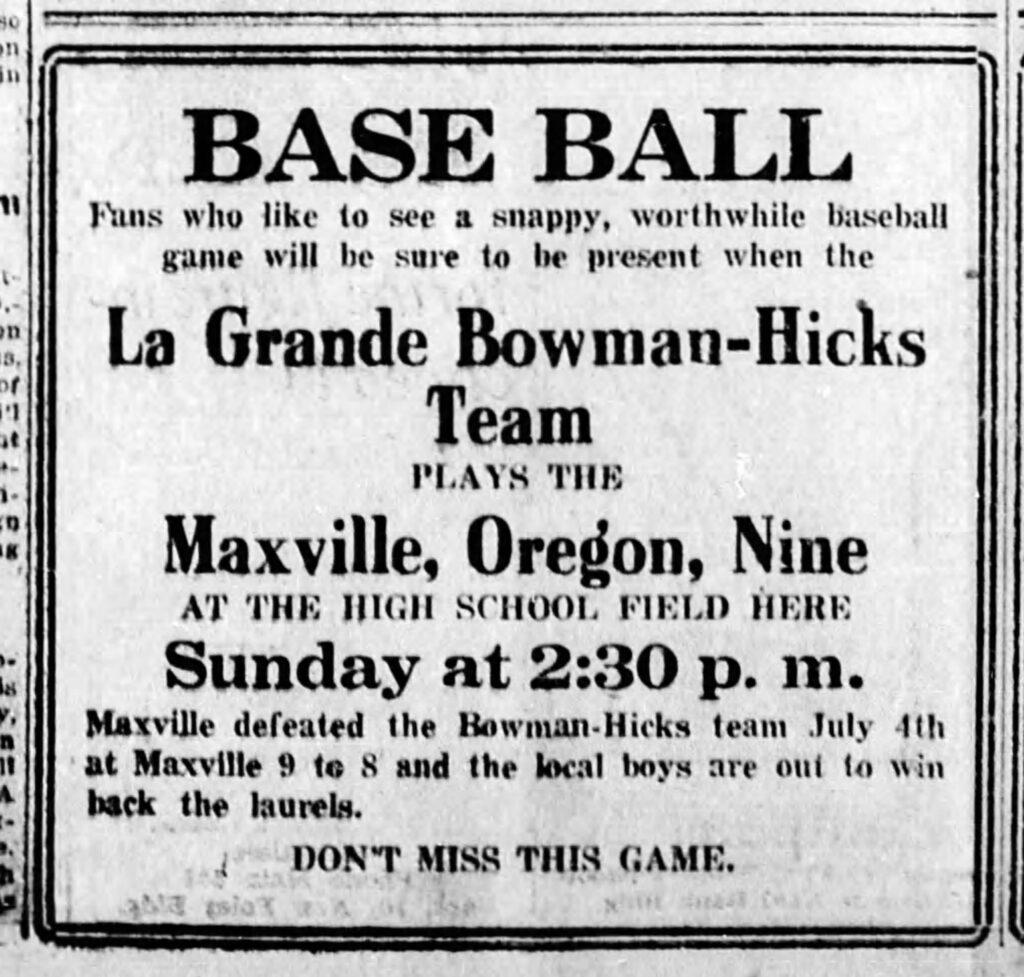

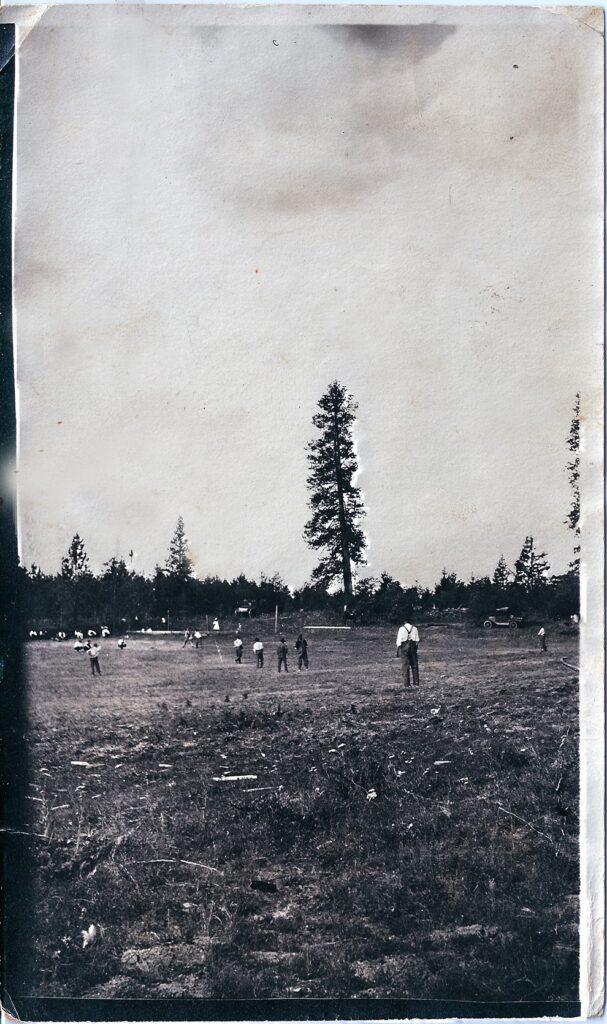

Henry Newt Ashby, formerly of the Long-Bell Lumber Company, served as the general manager for Bowman-Hicks’s western operations and was tasked with turning the isolated area in the forest into a livable work town. Maxville residents would need access to water, buildings for housing and schools, and railroad lines for moving lumber from the woods to the mill and then to market. In 1925, The Timberman, a national trade publication, reported that the town had “a post office, a store, a hotel, and permanent housing for married employees,” as well as a commissary where residents could use company tender to buy provisions. Maxville was unique from other mill camps; not only did it provide housing for unmarried seasonal male workers, but also for families of laborers. It also had schools (though separate ones for each race) and even a baseball field, which signaled the company’s intent that Maxville would be a permanent operation.

“I remember the town of Maxville. It was a little different than a typical logging camp because families were there. Usually camps were just the male end of it, but it was a family deal.”

—John Gregory, MHIC Oral Histories

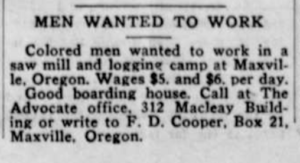

Recruiting Workers

Early recruits to Maxville included local settlers, migrants from other states, and Greek immigrants. Each would play their part in building the new town. Greek immigrants would build and maintain the railroads, while locals and migrants constructed houses and other buildings. A log building to house the Bowman-Hicks Lumber Company business operations and serve as a meeting place for Maxville residents was the first to be constructed, followed by housing for workers. Bowman-Hicks also actively recruited African Americans workers through their southern networks in Louisiana, Arkansas, and Mississippi, doing so despite Oregon’s Exclusion Laws.

The first Exclusion Law prohibiting African American settlement had been enacted in 1844, when the Provisional Government of Oregon excluded Black settlement within its borders. Despite Oregon voters’ opposition to slavery, an exclusion clause was written into Oregon’s 1857 Constitution. It stated:

“No free negro or mulatto not residing in this state at the time of the adoption of this constitution, shall come, reside or be within this state or hold any real estate, or make any contracts, or maintain any suit therein; and the legislative assembly shall provide by penal laws for the removal by public officers of all such negroes and mulattoes, and for their effectual exclusion from the state, and for the punishment of persons who shall bring them into the state, or employ or harbor them.”

Despite it being rendered moot by the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1866, the Exclusion Clause remained a part of the state constitution until it was formally repealed in 1926. Although it was inconsistently enforced, it had a searing impact on the African American community. The few African Americans who did live in the state faced a number of challenges, including exclusion from housing and public schools, intense economic disparity, discrimination, and the threat of violence. Even at the height of the first Great Migration (1910–1940), when an estimated seven million African Americans left the South for the North and West, Oregon’s Black population remained comparably low while neighboring states Washington and California saw increases in their Black populations. Even with the Exclusion Laws still being on the books in 1923, Bowman-Hicks successfully began recruiting skilled African American workers to the state from relationships cultivated in their southern mills.

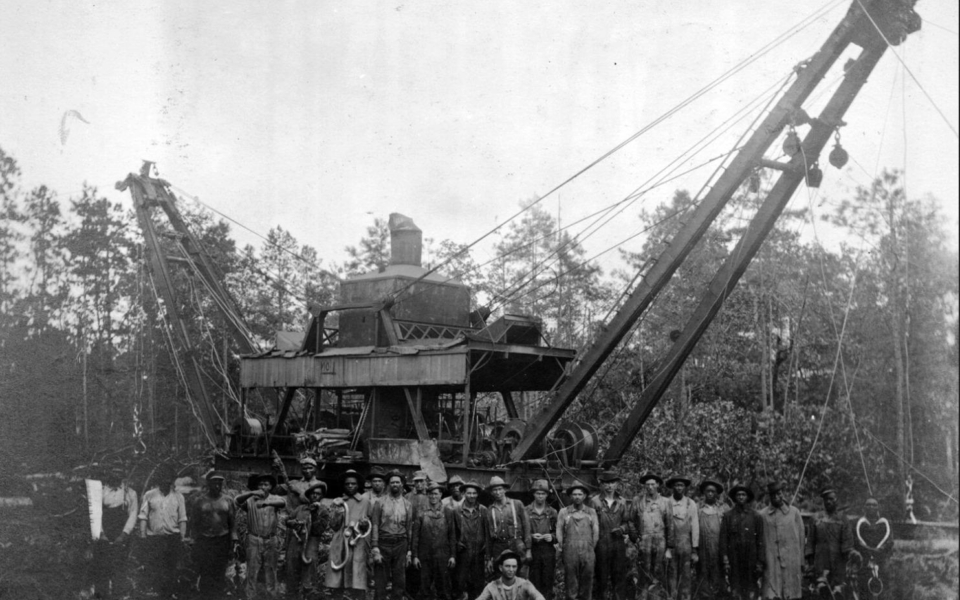

In the early twentieth century, the lumber industry was one of the largest employers of workers in the Southern states, and African Americans made up a sizable portion of that workforce. By 1910, more African American men in the Southeast were employed in lumber than in the textile, iron, and steel industries. For many African Americans, seasonal lumber work filled in gaps from farming’s inconsistent profits, which was impacted by the boll weevil infestation, unfair pricing, and discrimination. Between harvest and planting season, when work was slow, farmers would work in sawmills or as loggers. After World War I, with increasing demands for lumber and the growth of mill towns, employers began to offer more year-round work. By 1920, Black farmers began leaving struggling farms for more permanent work in the lumber industry, a choice made easier by company towns that housed both workers and their families. As timber reserves began to decline in the South, Black lumber workers found new opportunities in unexpected places. In one remarkable instance, owners of the mill town of McNary, Louisiana, moved 500 people, operations, and buildings west to establish McNary, Arizona, a predominantly Black mill town in the northern part of the state.

“My dad migrated to Maxville from Arizona. But back in the South, when my dad worked in logging, he started working at age 13 in the lumber mills. When the timber ran out, the lumber mill moved to a different location. So my dad moved from Louisiana to Arizona . . . and then the timber ran out. It got bad in Arizona and my dad moved here I think with Bowman-Hicks.”

—Frank Marsh, MHIC Oral Histories

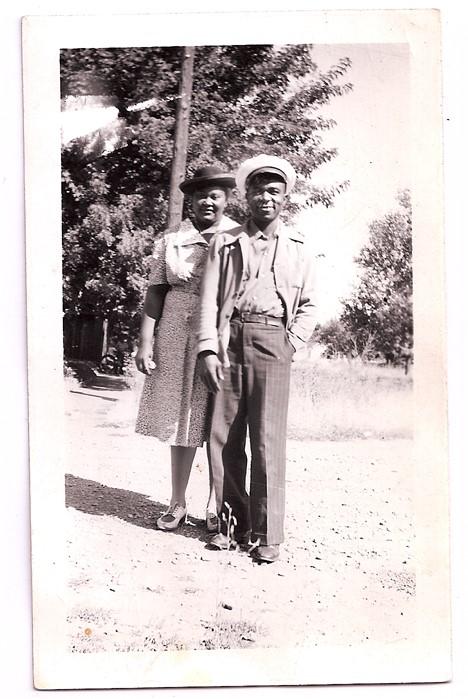

Efforts to recruit African American loggers were helped by the changing fortunes of places like McNary. By the late 1920s, at least 40 to 60 African Americans workers and their families called Maxville home.

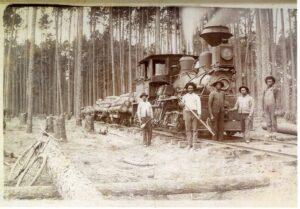

Working in Lumber

Some of the first African Americans to arrive in Maxville were the Lowrys and the Trices from Arkansas, the Pattersons and the Marshes from Louisiana, and the Baggetts from Mississippi—families who migrated mostly on trains and in boxcars to work in the forests.

They participated in the physical setup of the logging camp, beginning with the construction of the railway lines to Bishop Meadows, working alongside the Greek immigrant laborers. Logging and mill jobs in Maxville were also segregated, with Whites holding the higher paying jobs, such as section foremen, choker setter, or supervisors. In contrast, African Americans often did the most arduous and dangerous work, like felling trees and log cutting. Logging was a potentially lethal line of work.

“[D]uring that period the number of people—Black, White, that worked in the woods, there was invariably one or two people per year that were killed. . . When I left here, there were still lots of people in wheelchairs and lots of people that were killed, not only out there, but down at the mill.”

—Bob Chrisman, MHIC Oral Histories

However, they worked in integrated crews. Building trust with your fellow worker was crucial and could be life-saving. Ruth Carman, wife of a White logger, remembered Lucky Trice, an African American logger, as a hero and family friend. He saved her husband’s life after a logging accident by carrying him on his back out of the forest to the company doctor. Resultingly, loggers developed interdependent relationships for survival and for practical reasons. These sentiments often overflowed into both family and social life.

Not all local communities embraced the new migrants. In the early 1920s, the Ku Klux Klan set up its first Oregon chapter, which quickly grew to more than 60 local chapters and even had the support of the governor. The Klan made its way to Maxville but didn’t get the outcome they intended:

“Well, it would probably be about the middle ‘20s—a group of Ku Klux Klan members with their hoods on showed up at Maxville. (J. D.) MacMillan, who was the superintendent, and Jim Criley, who was the woods boss, they told them to get the hell out of Maxville. They said, don’t you people ever come back. Jim Criley says, maybe you guys have a mask to fool us, but he said, I know who you are. He said I don’t ever want to see your face around here again. So that was the end of the Ku Klux Klan.”

—Alen Dale Victor, MHIC Oral Histories

Local workers also took issue with the competition the new loggers represented. The Oregon Statesman in 1924 reported a complaint had been made to the state labor commissioner that asked if “anything can be done to stop the Bowman-Hicks Lumber Company from shipping in Negros to take the place of white labor.” The commissioner responded, “There is nothing that can be done to stop the company from bringing in the dark men.” However, the isolated location and the autonomy of the company town served as a buffer, protecting African American workers from the worst displays of racial violence.

Degrees of Freedom in a Lumber Town

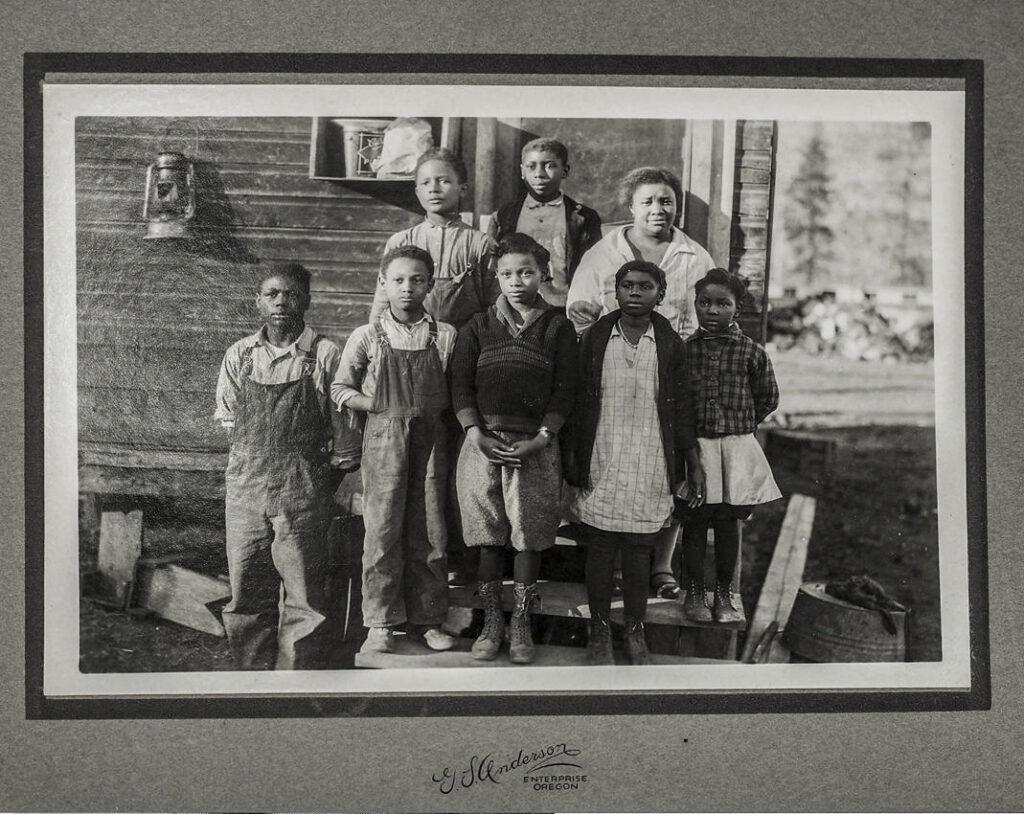

The Jim Crow system that controlled life in the U.S. South also migrated to Maxville. African Americans lived on the north end of the town, Whites lived on the south end. And even with the town’s small population, Black and White children were taught in separate schools. Nevertheless, for African Americans, the challenges they faced in Maxville were not as severe as the deeply entrenched racism they left in the South.

Isolation, economic dependency, and the remoteness of the location helped forge meaningful bonds across the racial divide. Residents of Maxville found ways to connect, forming an interracial community that was unusual for the times. They all shared the same company doctor, company lawyer, and town amenities. The company’s Fourth of July celebration was planned and attended by both White and Black residents. Black and White children played together after school, whether in a riverbed, catching frogs, sledding down a snowy path, or on the railroad tracks. There were two baseball teams, one White and one Black, and when not competing against each other, the teams would be combined into a very formidable force to play teams from nearby towns.

The challenges of life in Maxville bonded the town’s women together, starting with their plight as loggers’ wives. Women’s work, regardless of their race, was equally demanding and grueling. Both races found life in Maxville to be rugged and harsh, especially in the winter months. Few houses had indoor plumbing, and the harsh winters made everyday tasks particularly challenging. Autumn was an important time for women’s work because it was a time of harvest, canning, hunting, and fishing to prepare for the winter months, and that preparation or lack thereof determined a family’s survival. Pearl Alice Marsh, the daughter of African American logger Amos Marsh and author of But Not Jim Crow: Family Memories of African American Loggers of Maxville, Oregon, described her mother’s daily routine:

“Mom awakened at 4:30 am to prepare the wood stove to warm the house before everyone awakened while also preparing Dad’s work clothes, lunch, and breakfast of bacon, eggs, fresh biscuits, and coffee before Dad left for work. By 6:30 am, it was time to awaken the kids, feed them, and get them ready for school. By the time we were off to school, it was time for daily chores. With five children and a logger husband, Mama had to wash almost every day. By the time the clothes were washed and hung on the line to dry, it was time to prepare our hot lunches. After our hot lunch, we were back at school, and Mom’s chores continued. The afternoon was spent house cleaning, ironing, and going to the store to buy groceries and putting on supper. By 3:00 o’clock Mama and her friends were gathered together at one of their houses to quilt, crochet, and embroider for the family. By 5 pm, Papa was home, and the men organized their tools. After the men finished organizing, supper had to be served, the kitchen cleaned, children set to task with their homework. . . . After a little outdoor play, we were cleaned and put to bed while Mama told us a story.”

For some Black women, the isolation and lack of kinship led them to relocate their families to the larger La Grande, a rail and mill town of 8,000 people roughly 50 miles southwest, while their husbands continued to work in Maxville. In La Grande, they found the support and institutions of a larger Black community. For those who stayed in Maxville, bonds between races were made, yet African Americans were fully aware of the delicate balance they faced. According to Ester Wilfong Jr., a former Black resident, “you did what you were supposed to do, you kept your mouth closed, and you did not step out of line.” Loggers such as Joseph (Pa Pat) Patterson and Lucky Trice would help new African American recruits adjust to the tricky nuanced social relations of the interracial town. They would also deal with troublesome recruits whose behavior risked upsetting the social balance and making things difficult for Maxville’s Black residents.

“But they always called Lucky ‘the Mayor of Maxville.’ . . . He was a good man. Lucky was a real good man. If things were bubblin’ over, he kind of kept the lid on ‘em, even when they hit La Grande here, he did it. I know one time I had an employee shipped out here from Kentucky that got to tearin’ around and runnin’ through the colored population and Lucky called me up in Wallowa and told me, ‘Ship that kid back to Kentucky.’ And that’s what I did.”

—John Gregory, MHIC Oral Histories

Many residents, both Black and White, found their time in Maxville meaningful in regards to social relations, despite the challenges they experienced. For some of the White residents, it was their first encounter with African Americans. And for the African American residents, they were able to engage socially in ways that would have been unimaginable in the South.

Maxville Closes

A downturn in the national lumber industry that had begun in the mid-1920s, followed by the onset of the Great Depression and the rising costs of using railroads for transporting lumber, led to Bowman-Hicks closing Maxville in 1933. Most of its residents moved by the mid-1930s to nearby towns such as La Grande, Wallowa, Enterprise, and Promise. Remaining families moved by the late 1940s. Building and structures were removed and relocated throughout the county. The Bowman-Hicks Lumber Company finally dissolved in 1975.

Reclaiming The History: Maxville Today

Ninety years after the mill closed, the legacy of Maxville lives on through the hard work and commitment of descendants of former residents. Pearl Marsh highlights family histories in her book But Not Jim Crow, Family Memories of African American Loggers in Maxville, Oregon. And Orvall Carper Hafer has published two volumes of 100+ Years The North Woods of Wallowa County.

In 2003, Gwendolyn Trice, who was born and raised in nearby La Grande, roughly 50 miles southwest of Maxville, made an unexpected discovery: her father, Lafayette “Lucky” Trice had been a logger in Maxville. He was one of the first African Americans to be recruited to the town from Arkansas in 1923. Retracing her father’s steps and uncovering the history of Maxville lead to her eventual move back to the area. After locating descendants of former residents, she conducted oral histories and began collecting and preserving old photos and artifacts. In 2009 PBS’ Oregon Experience produced “The Logger’s Daughter,” which follows her discoveries. In 2008, in part to house the photos and interviews she had collected, Trice opened the Maxville Heritage Interpretive Center in Joseph, Oregon, roughly 40 miles south of where the town once stood. MHIC serves as a cultural resource to preserve the remarkable history of Maxville and similar multiracial timber communities in the Pacific Northwest.

Since opening, MHIC has educated visitors and students alike through permanent and traveling exhibitions, and with site tours. Recently, MIHC purchased a 240-acre plot that includes the land where the town once sat. And MHIC has embarked on a robust preservation initiative which includes an archaeological program and the rebuilding of the main lodge at the site. Through MHIC advocacy’s Maxville has recently been designated as an archaeological site by the state of Oregon.

Each year, the center hosts an annual meeting that brings together descendants of former Maxville residents and residents of surrounding communities to celebrate. For the 100th year anniversary of the founding of the town in 1923, MHIC hosted a two-day gala that included music, food, speakers, and activities at the old town site. Governor Tina Kotek even designated June 3, 2023, as “Maxville Heritage Day.” These actions—the archeological work, restoration of buildings on the town site, the exhibits and educational outreach, and the ongoing commitment of the town’s descendants to celebrate the town’s past—assure the history of Maxville and the legacy of this unusual lumber town will reach and educate new generations.

Additional Resources

For additional information on the history of Maxville and the surrounding communities, please visit The Maxville Heritage Interpretive Center.

Many thanks to archivist and librarians at the Wallowa History Center, Eastern Oregon University Library, The History Center of Diboll and Southern Forest Heritage Museum.

Thanks to Aaron Miles Jr., Director of Natural Resources for the New Perce Tribal Government, for consulting on the history of the Nez Perce and to Pearl Marsh, descendant of Maxville and author of But Not Jim Crow: Family Memories of African American Loggers in Maxville, Oregon. And thanks to Sadie Kennedy of the Wallowa History Center.

For further reading:

Barklow, Irene. School Days in the Wallowas. Enchantment Publishing of Oregon, 1992.

Belew, Ellie. About Wallowa County: People, Places, Images. Pika Press 2000.

Fickle, James E. The New South and the “New Competition”: Trade Association Development in the Southern Pine Industry. University of Illinois Press, 1980.

Jones, William Powell. The Tribe of Black Ulysses: African American Lumber Workers in the Jim Crow South. University of Illinois Press, 2005.

Josephy, Alvin. The Nez Perce Indians and the Opening of the Northwest. Houghton Mifflin, 1997.

Lembcke, Jerry, and William M. Tattam. One Union in Wood. Harbour Publishing, 1984.

Marsh, Pearl Alice. But Not Jim Crow: Family Memories of African American Loggers in Maxville, Oregon. Pearl Alice Marsh, 2019.

McLagan, Elizabeth. A Peculiar Paradise: A History of Blacks in Oregon, 1788-1940, 2022.

Orvalla, Hafer Carper. The North Woods Of Wallowa County. Vol. 1, Vol. 2, Maverick Publications, 2015.

Taylor, Quintard. In Search of the Racial Frontier: African Americans in the American West 1528-1990. W. W. Norton & Company, 1999.

Prepared in 2023 by Yolanda Hester and Elizabeth Flowers of Frameworks and Narratives, LLC.