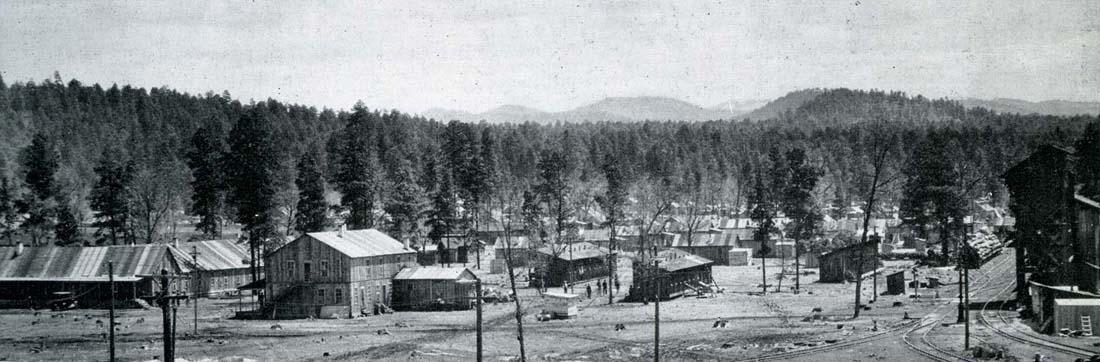

McNary, Arizona: A town on the move

When my wife and I moved from Washington, DC, to Durham in 2003, we only half-jokingly said we wished we could move our friends and some of our favorite restaurants and stores with us. When the Cady Lumber Corporation decided to move in 1924 to get access to more timber, its owners did just that. It moved all of its employees. And their families—800 people in all. From Louisiana to Arizona. This was the very definition of moving lock, stock, and barrel.

At the time, moving a lumber camp was not unheard of. A logging company would put the small houses and other buildings on railroad cars and move them to the next location a few miles down the line.

Converted railcars often served as housing and offices for loggers. This one was used by the Crossett Lumber Company, Crossett, Arkansas. (FHS4448)

But in 1922, William Cady realized that his lumber and milling company had cut out nearly all the yellow pine around McNary, Louisiana. He realized that it would be cheaper to abandon the land than it would to undertake reforestation. He and his business partner James McNary had an unusual idea. They would buy an existing mill operation and relocate their employees to another region of the country. McNary and Cady wanted to keep their skilled loggers and mill labor because the owners felt they were the best at what they did.

McNary first scouted the Pacific Northwest and then Mexico. He then found the mill town of Cooley, Arizona, on the Apache Indian Reservation. He and Cady purchased the defunct Apache Lumber Company for $1.5 million in a deal that included all of Apache's timber holdings and its milling operations in Cooley and Flagstaff. The deal had to be approved by the Bureau of Indian Affairs and also the U.S. Forest Service because the agency oversaw timber on the reservation and because some of the timber was coming off of the Sitgreaves National Forest. In fact, nearly all of the timber Cady contracted for was on government land, and the government would pick up the cost of fire fighting and reforestation. Cady Lumber then spent $3.5 million to install an all-electric plant with three band saws. For marketing purposes, the company received permission from the federal government to rename Cooley as McNary. With that, it was time to pack.

On February 7, 1924, the last log in the McNary, Louisiana, plant was cut. Three days later employees boarded special trains with their baggage and equipment and moved west to the new home that awaited them. They were moving from the heat and humidity of Louisiana to a town at 7,300 feet above sea level, a place where they measure annual snowfall in feet. To say that there would be some adjustment required to get used to the new surroundings was an understatement. But it wasn't just the weather.

Of the 500 employees who moved, almost all were African American. According to the 1920 federal census, there were 8,005 African Americans in the entire state of Arizona—or 2.4% of the state's population. James McNary recorded in his autobiography that "there was a good deal of indignation in some quarters in Arizona over the importation" of the African American employees and their families but the threatened violence never materialized.

Once operations started in Arizona, the company also employed Native Americans and old homesteading Spanish and Anglo families in the area. According to McNary, each ethnic group constituted a quarter of the work force. Though living conditions in McNary, Arizona, were better than what was found in surrounding towns, it was nonetheless a company town (the company controlled all utilities, hospital, and schools, and owned the housing and only store in town)—and one that was segregated. Each group had its own section of town, with its own school. When adjusting to the climate or life in Arizona proved difficult for some African Americans, they left, only to be replaced by others coming from Louisiana who had heard about the good jobs and a degree of racial tolerance unheard of in the Jim Crow South.

The caption read, “A typical residence street in McNary, showing roomy, comfortable homes of employees of the Cady Lumber Company.” However, African American employees lived in a separate part of town called the “Quarters.” (below)

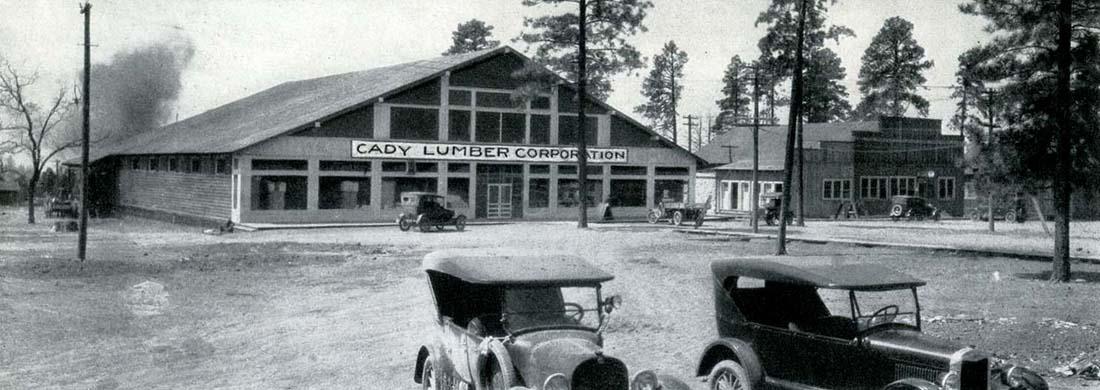

The company store. It was the only place in town where employees could shop.

In 1935, James McNary bought out William Cady after Cady Lumber collapsed and renamed the company Southwest Lumber Mills (later it became the Southwest Forest Industries.) Over the next two decades McNary modernized logging and milling operations and built a lumbering empire that after World War II "would challenge Weyerhaeuser, Georgia Pacific and other preeminent producers on the Pacific Coast." He also became involved in the work of the National Lumber Manufacturers Association. McNary sold his business interests in 1952 and became a man of leisure, publishing his fascinating autobiography This Is My Life in 1956 (for example, active in Republican politics on a national level, McNary was pals with Presidents Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover).

Eventually operations began shifting to the more modern Flagstaff plant. With that, the migration of workers began again. After a fire in 1979 destroyed the lumber mill in McNary, the remaining workers moved out, leaving McNary, Arizona, as deserted as its namesake in Louisiana.

Cover image from a photo tour pamphlet in the Southwest Lumber Mills, Inc., file.

◊◊◊◊◊

Both the topic of James McNary and the towns that bear his name are ripe for research. One could look at the business, the man, or the towns— through the lenses of social, racial, and environmental histories. FHS has materials on Cady Lumber and its move from Louisiana to Arizona and life there among the big white pines. The move to Arizona and the history of the company was captured in a lengthy article in American Lumberman magazine in 1926. In addition to this article and McNary's autobiography, we have the records of the National Lumber Manufacturers Association, which contains McNary's correspondence from when he was its president from 1937 to 1939. The Cady Lumber Corporation materials include copies of the contracts signed by Apache Lumber in 1918 with the government and when Cady bought them out. We also have information on Southwest Forest Industries, including several annual reports and press releases from the 1980s. Secondary sources include Curtis Wienker's article-length study of the town, "McNary: A Predominantly Black Company Town in Arizona" (Negro History Bulletin, 1974) and Arthur R. Gómez's 2001 study "Industry and Indian Self-determination: Northern Arizona's Apache Lumbering Empire, 1870-1970," in Forests Under Fire: A Century of Ecosystem Mismanagement in the Southwest. The Cady operations, which at one point was the largest contract producer of timber in northern Arizona, are also discussed in a history of Region 3, Timeless Heritage (see page 74). Speaking of northern Arizona, the Arizona Historical Society has some papers on Southwest Forest Industries and Northern Arizona University has images and 3 related oral histories.

The April 10, 1926, issue of “American Lumberman” magazine featured a 55-page article on the Cady Lumber Corporation operations in McNary and Flagstaff.