Black Woman in Green: Excerpts from Gloria Brown’s Memoir

In 1999, Gloria Brown became the first female African American forest supervisor in the U.S. Forest Service. Gloria cowrote her memoir Black Woman in Green: Gloria Brown and the Unmarked Trail to Forest Service Leadership (Oregon State University Press, 2020) with Donna Sinclair, who shares her reflections on working with Gloria and excerpts from the memoir. Donna is giving a virtual lecture on the U.S. Forest Service in the civil rights era on Feb. 25.

In 1999, Gloria Brown became the first female African American forest supervisor in the U.S. Forest Service. Gloria cowrote her memoir Black Woman in Green: Gloria Brown and the Unmarked Trail to Forest Service Leadership (Oregon State University Press, 2020) with Donna Sinclair, who shares her reflections on working with Gloria and excerpts from the memoir. Donna is giving a virtual lecture on the U.S. Forest Service in the civil rights era on Feb. 25.

I first encountered Gloria Brown in 2004 through a student-recorded interview. I will always remember the rich, steady timbre of her voice and the calm, matter-of-fact way she described the events that led her to become the nation’s first female African American forest supervisor in 1999. We didn’t meet until 2013, when I interviewed her for my dissertation, “Caring for the Land, Serving People: Creating a Multicultural Forest Service in the Civil Rights Era” (Portland State University, 2015). Two interviews and several discussions later, she asked me to help write her story. I eagerly agreed.

A city girl from Washington, D.C., Gloria once dreamed of becoming a television journalist. But in 1981, at age 30, while working as a dictation transcriber for the U.S. Forest Service in its Washington office, she instead became a widow with three children and an uncertain future. Her husband’s sudden death quickly forced her to pull their children from private school and move the family to an apartment in a bad neighborhood in Maryland. These events fueled Gloria’s ambition to do something unprecedented at the time: supervise a national forest. Such lofty objectives didn’t ignore the reality of the moment. As she once told me, “I had to feed those kids.”

Our book traces Gloria’s remarkable journey from an unlikely beginning as a transcriber with no forestry background or rural exposure to managing two national forests, first Oregon’s Siuslaw and then California’s Los Padres. Within the context of racism in public lands management and a changing government agency, Gloria used clear-eyed strategy, a warm personality, good humor, and sheer force of will to advance professionally in the Forest Service.

The book relies on a mixture of the spoken and written word as Gloria and I talked, wrote, read aloud, and revised together to tell the story of a woman and an organization, a mother and a society, a forester and a leader. The excerpts that follow begin with Gloria’s first field experiences. They end as she arrived at the Siuslaw. By then, she had worked in several overwhelmingly white communities, completed a natural resources program program at Oregon State, conducted civil rights trainings, and shattered glass ceilings, all while raising her children alone.

The first significant step on her new career path came in 1987 when Gloria transferred from Washington to the regional office in Missoula, Montana, to work as a public affairs officer. There, she had her first real encounters with outdoor work and agency policy, and gained confidence in her ability to move up in the Forest Service.

“My early training in Montana brought me face-to-face with the land itself… I [also] found myself surrounded by people who had worked half their lives in the woods, who shared stories about hunting and fishing, activities I had never done. The talk around the fire educated me. I had all the questions: Where did these huckleberries come from? Do we have to worry about bears or mountain lions? What about snakes? I found out there were black bears, but no dangerous snakes. I also learned to identify scat. I had never seen a cow patty, much less grizzly poop. The former is round, crusted over, and flat; the latter resembles dog poo, but bigger. I learned that huckleberries grow abundantly among the redwoods and Douglas-fir. Native people had been picking the berries each summer for thousands of years. Non-Natives had turned harvesting into an enterprise that included wine, candy, and jellies. Now, the little purple berry was at the heart of many multiple-use conflicts on national forest lands” (p. 26).

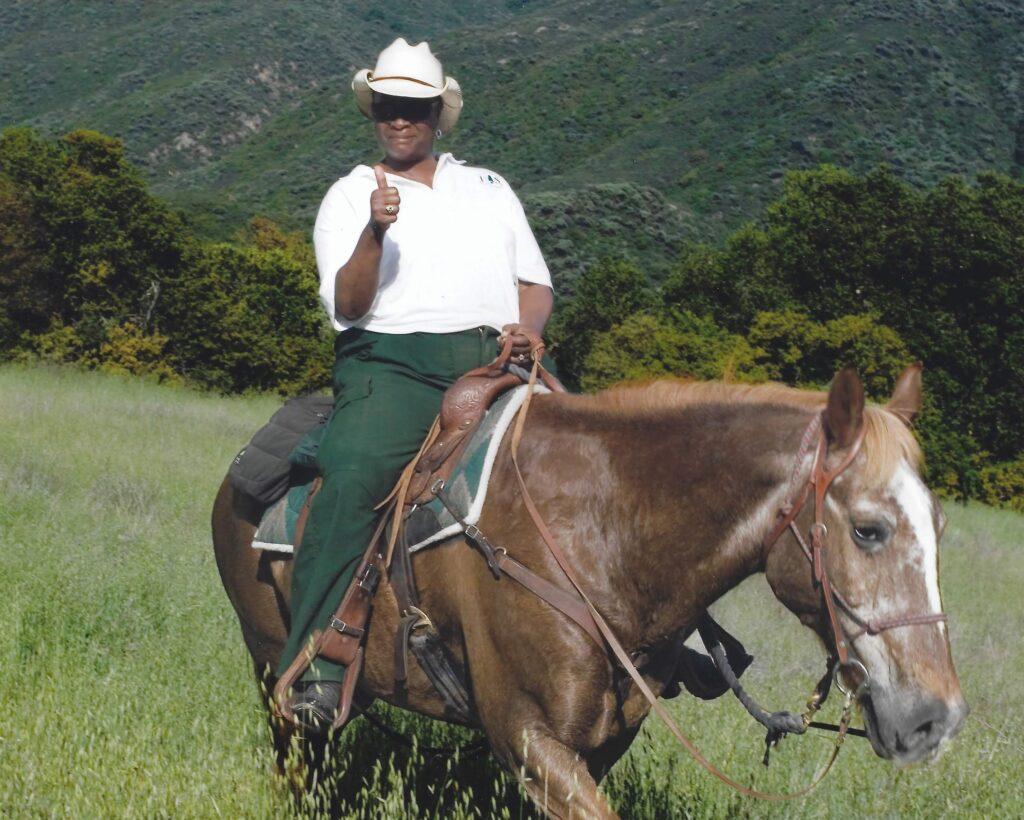

Gloria Brown riding Smokey on the Los Padres National Forest not long before her 2011 retirement.

“I had never ridden a horse before, had never even touched a pony; yet, here I was learning to mount, ride, and steer a live animal. At first, I was too excited to be afraid. As we clomped down narrow trails over canyons, our guide told me not to worry. Then I realized that if my horse fell over, I would surely die. I’d never thought about dying at work before, but as I looked down from the back of a five-foot-high animal into a ravine ten feet below a trail already hundreds of feet high, it suddenly felt possible. I stopped looking down. This was one experience of many that made say to myself, I can do this!” (p. 27).

Forest Service chief Mike Dombeck visited the Mount St. Helens National Monument when Gloria was in charge.

After earning a certification in the natural resources management program from Oregon State University in 1991 and working as a district ranger, Gloria left the Forest Service for a brief stint with the Bureau of Land Management. She returned in 1997 as Monument Manager for the Mount St. Helens National Monument on the Gifford Pinchot National Forest. Her two-year supervisory stint in this unusual assignment provided opportunities to hone her management skills and increase diversity within the Forest Service employment pool.

“The assignment at Mount St. Helens gave me more opportunity than ever before to bring minorities into the workforce, something I found exciting. It takes real commitment by leadership to bring people of color into the Forest Service, and as downsizing took hold of the region, in the 1980s and early 1990s, efforts lagged. I finally had the power to do something about diversity, an issue I saw as important not just for employees, but also for our many thousands of visitors….

Why would I care about hiring people of color? Aside from my personal interest, I believe that representation matters. Representation counts because of the message employees send to the public about belonging. I loved watching children’s faces light up when they interacted with people who looked like them or spoke to them in their native language. I knew this feeling intimately because I remembered meeting a black teacher when I was in grade school and realizing that I could grow up and teach or get some other professional job. It gave me hope for a future beyond domestic work, since that’s what a lot of black women did, especially in the South” (p. 125).

Gloria Brown at Karnowsky Creek on the Siuslaw National Forest, where restoration of the meandering waterway earned the prestigious Thiess International Riverprize from the International RiverFoundation.

In 1999, Gloria’s dream came true. She became forest supervisor of the Siuslaw National Forest, the first African American woman in the United States to achieve this goal.

“I was heading back to Corvallis, only this time I had truly arrived: I was the first female African American forest supervisor in the nation. I was proud of my tenure at Mount St. Helens, and this new appointment felt like the reward for a job well done. The Eugene Register-Guard, Corvallis Gazette-Times and the Oregonian newspapers introduced me to my new constituency as a pioneer blazing a trail from Washington, DC, through Montana, Washington State, and Oregon. My position as forest supervisor was new territory not only for me, but also for the Forest Service. We were betting on each other, and the stakes were high. I had watched and participated in the continued unfolding of Mount St. Helens’ ecological network, the flora and fauna that brought back an ecosystem. Just as wildlife, birds, and sprouts of green reemerged on the once-barren landscape, so I realized that I, too, had blossomed toward my new assignment. I knew my dream job would present huge and unexpected challenges.

“This would be a test of my survival as a leader, and of the Siuslaw National Forest and its employees. It was also a test for women of color. There were a few, very few, other black women reaching for high-level positions in the Forest Service. Melody Mobley, a forester, had held a staff position in the WO, but left the agency a few years earlier. Leslie Weldon, a wildlife biologist, also had a staff position in DC. Now, it was 1999, and I was the first black woman to manage an entire national forest—ever. Weldon, who later became deputy chief for the National Forest System, followed me the next year as the second African American female forest supervisor—on the Deschutes National Forest. Leslie later said she stood on my shoulders to get there” (p. 131–32).