From the Louisiana Swamps to Major League All-Star

This week’s Major League All-Star Game in Anaheim, California, brings to mind baseball history as seen through the FHS Library. In the early 20th century, in addition to the two major leagues in the Northeast and the numerous minor leagues around the country, semi-pro baseball teams were sponsored by business owners—including lumber mill owners—and business organizations like the Hoo-Hoos. Baseball was the national game in America, played in towns big and small. In addition to trade publications like American Lumberman, local papers like the New Orleans Times-Picayune covered baseball games between company teams as thoroughly as the large urban daily newspapers did games on the senior circuit. And baseball at this level was big business. In 1908, the trade publication American Lumberman reported rumors of the formation of a "national league of lumbermen" teams. With its collection of trade publications, the FHS Library and Archive is a great resource for investigating this neglected aspect of baseball history.

We’re particularly intrigued by one team, the Patterson Greys (sometimes spelled "Grays") of Patterson, Louisiana, the “crack amateur baseball team of the F.B. Williams Cypress Co.,” as a 1921 article called them. Built by Frank B. Williams, the F.B. Williams Cypress Co. dominated the cypress logging and milling business in the region and helped establish a national market for cypress. Williams may have built the town of Patterson, but his son's baseball team put it on the map. The Patterson Greys dominated the sport on a regional level but also had a national impact.

One of Frank's sons, Harry “H.P.” Williams, described as “an ardent sportsman and particularly addicted to baseball,” organized and managed the team for many years (we’re not sure when the team started or disbanded). The team regularly competed for the Louisiana state championship against other “amateur” teams, and also traveled the Deep South playing other semi-pro teams and even college squads. His players received $150 a month plus room and board. Williams paid bonuses for outstanding plays at the plate and in the field.

The Patterson Greys, in 1921, with manager H.P. Williams. (from American Lumberman, click to enlarge)

What’s most fascinating is that the quality of players was such that Williams sold a number of them to the New York Giants and other clubs. This same 1921 article claims that he did not stock his Greys with experienced professional players “but fill[ed] up his string with promising Louisiana boys, some of whom are college students.” Given that F.B. Williams Cypress Company (now Williams, Inc.) was one of the largest lumber companies in the United States in the early 20th century and paid its players well, it wasn’t too surprising that the company team attracted such high-caliber talent from across the South. The article lists the handful of players Williams had sent to the major leagues who lasted about two years each: Ivy Griffin, Johnnie Monroe, John Paul "the Admiral" Jones, Dick Humphries, Sammie(?) Hale, and a shortstop name Doty. Eddie Morgan and Carl Lind lasted seven and four years respectively with the Cleveland Indians. The one who did have a long, successful career? Hall of Famer and 12-time All-Star Mel Ott (1934-45), perhaps the greatest right fielder of his era. For Williams, it was an impressive achievement just to send players from his mill-town team to the senior circuit, let alone the man they called "The Little Giant."

So how did this player pipeline that stretched from rural Louisiana to New York get established? According to Fred Stein, Met Ott's biographer, Harry Williams was old friends with the Giants' long-time manager, John McGraw, as well as Philadelphia Athletics' owner-manager Connie Mack. It’s possible that Harry was introduced to these men by his wife, the famous stage and screen actress Marguerite Clark, one of the most popular actresses of her day. Or scouts working for McGraw and Mack came through Louisiana looking for the next "Georgia Peach", a.k.a. Ty Cobb, and they met that way. We don't know. We’re still trying to find out.

We do know that after the F.B. Williams Company exhausted its cypress holdings (their employees are seen logging cypress in this footage), Harry and his brothers (who took over operations from their father by 1913) started closing down their four mills in 1929 and were out of the lumber and milling business by 1933. As luck would have it, oil and gas were discovered on company land during this time, and the company quickly shifted into those fields along with real estate development. As the mills were winding down, Harry—long fascinated with airplanes—entered the airplane design business with airplane mechanic and designer Jimmie Wedell. Together they built some of the fastest airplanes of the era and became pioneers in the airline industry in Louisiana. Harry died in an airplane accident in 1936. Today Williams, Inc., is owned and operated by the decedents of his brothers.

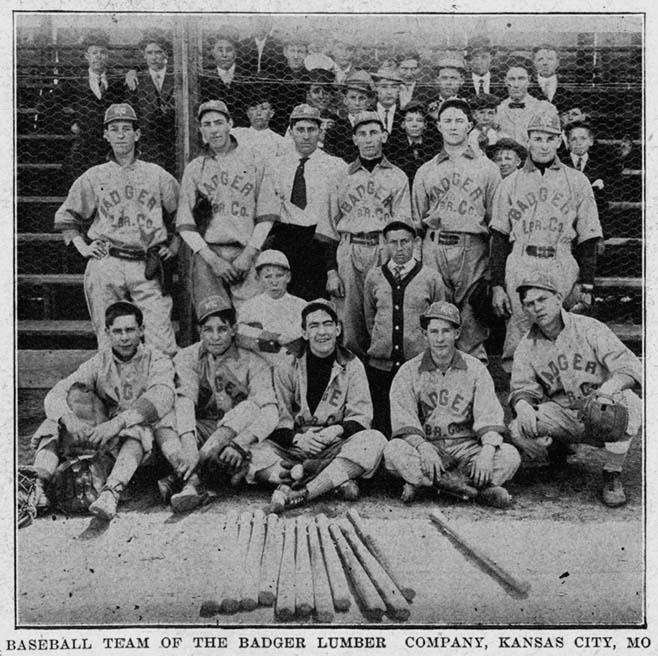

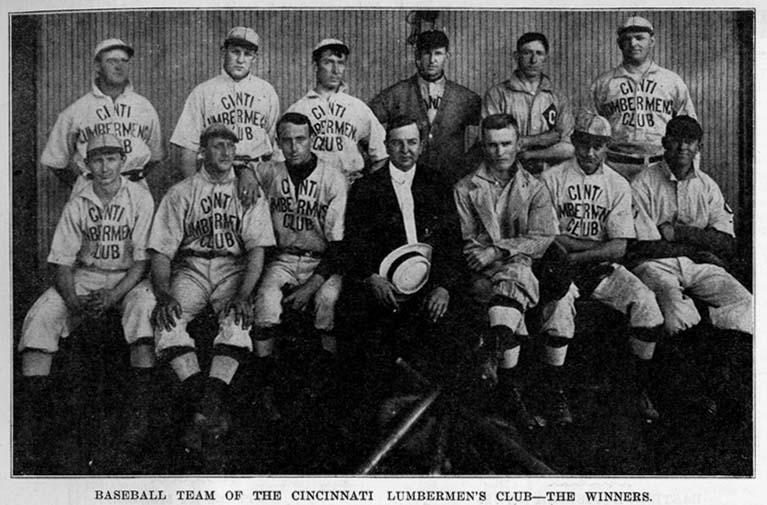

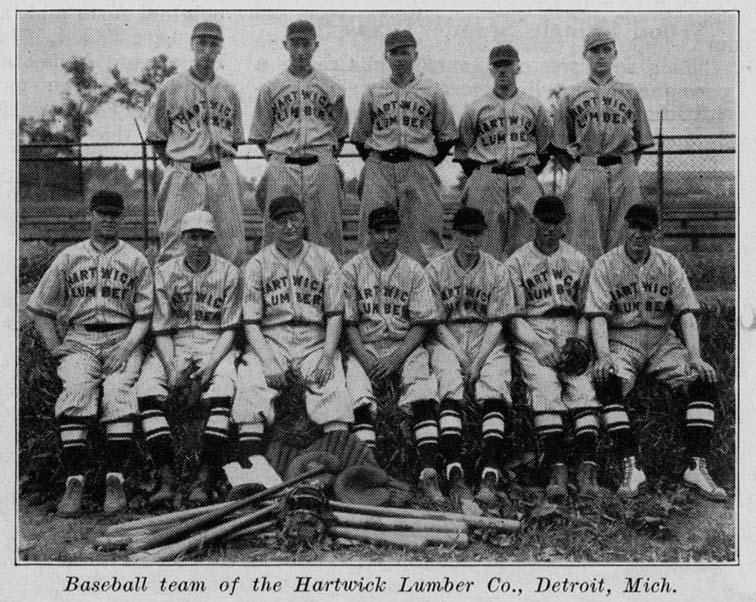

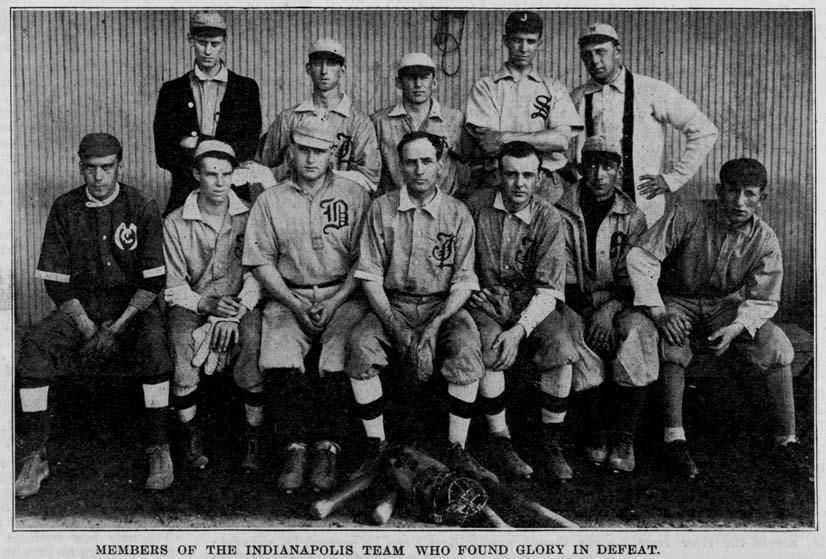

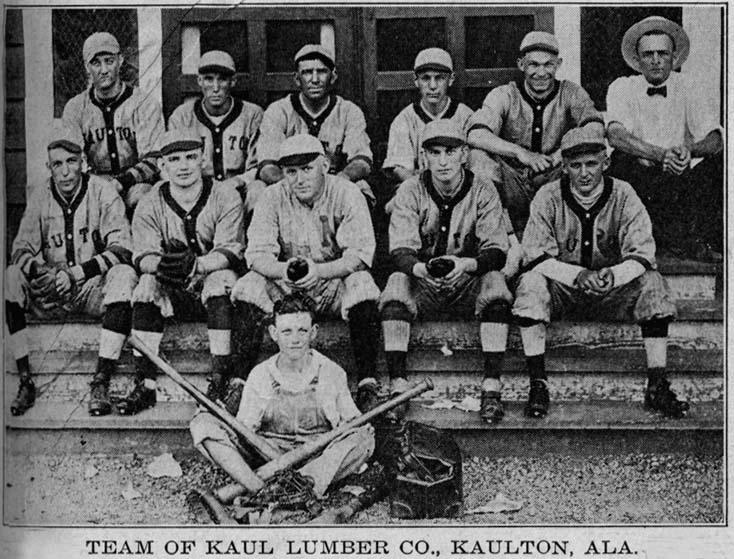

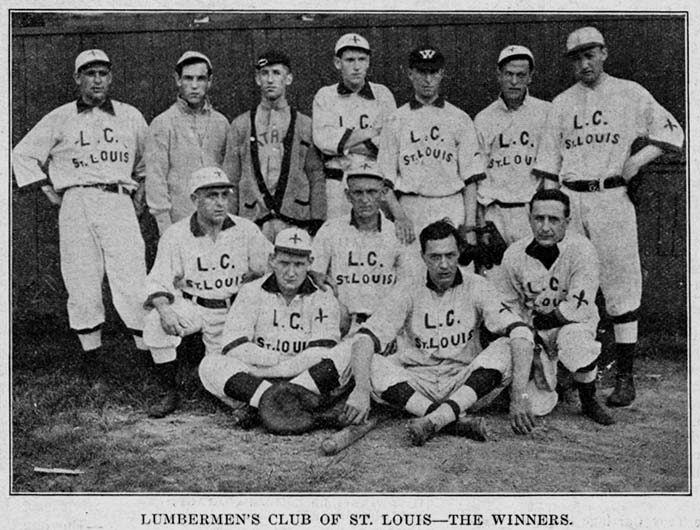

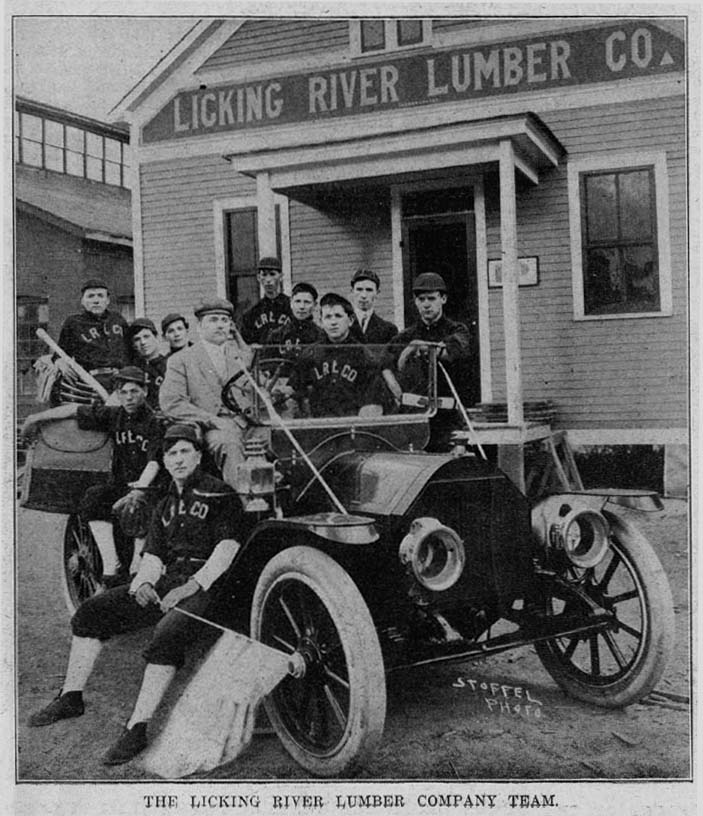

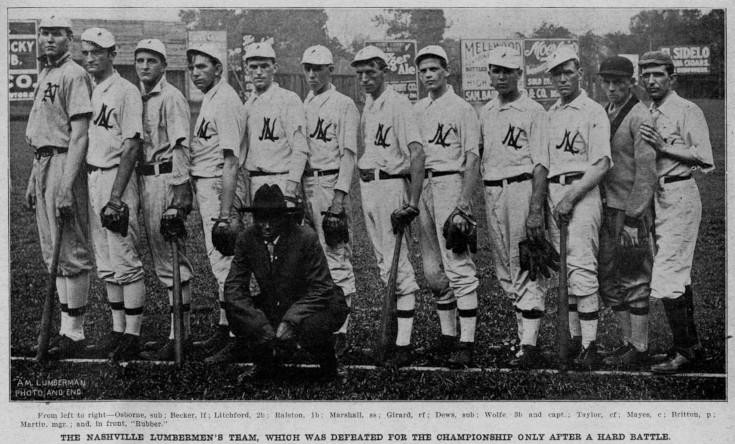

Enjoy selected photos below of some of the teams highlighted in American Lumberman from that era. Note how the various uniforms rarely incorporate a logo.