“We Were in Love with the Forest”: Protecting Mexico’s Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve

This blog post by Ellen Sharp and Will Wright is a working version of an article to be published in the Spring/Fall 2020 issue of our magazine Forest History Today. We are making it available beforehand because of the time sensitivity of the conservation issue it discusses. You can download a draft version of this post to read offline here.

The issue is that illegal logging in the overwintering habitat of monarch butterflies in Mexico, which appears to be increasing due to the impact of the pandemic on the tourist-based local economy, threatens their existence. The personal history of some of the rangers who patrol those areas may hold the key to the insect’s survival.

“My dad was one of the first to find the butterflies here. In fact, he was the one who found them,” Emilio Velázquez Moreno said into the tape recorder.1 I (Ellen) was seated on a rock across from him on a newly cut path above a meadow called La Lagunita on Cerro Pelón, the site where this discovery had taken place. I hadn’t planned on interviewing Emilio. He was a new hire for Butterflies & Their People AC, a forest conservation nonprofit I cofounded in 2016. But as soon as I finished talking to his more senior coworkers, Emilio tapped my arm. “Aren’t you going to talk to me?” And now I knew why: redemption. His family was better known in his community for exploiting the forest, not preserving it. Now that Emilio had a job stopping loggers instead of facilitating them, he wanted to claim this lineage and make sure his late father, the ranger Valentín Velázquez, was included in our butterfly history.

Butterflies & Their People forest guardian Emilio Velázquez Moreno in El Llano de Tres Gobernadores, Cerro Pelon in February 2020. Photo by Patricio Moreno Rojas.

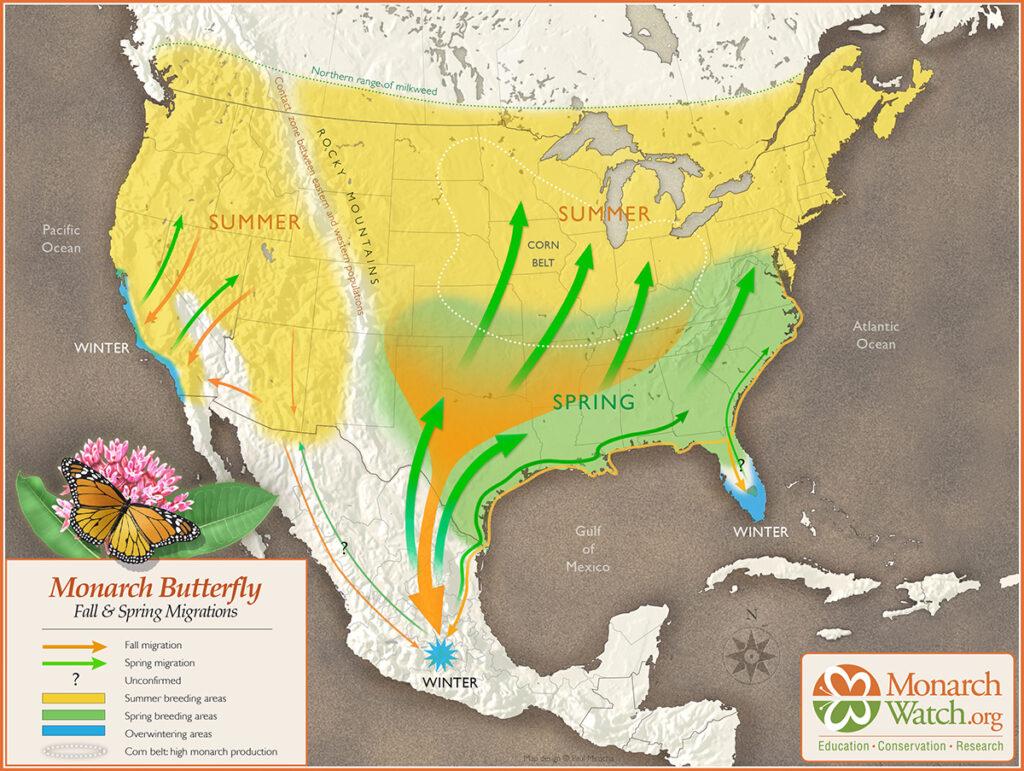

Although people in Mexico, United States, and Canada have for years delighted in the masses of monarch butterflies they saw every summer, no one comprehended the complexity and scope of this transnational spectacle until the mid-1970s. We now know that in autumn, most of the monarchs living east of the Rocky Mountains migrate southward to central Mexico, where they form colonies in a few acres of high-altitude boreal forest. Stands of oyamel fir (Abies religiosa) and Montezuma pine (Pinus montezumae) in the Transverse Neovolcanic Belt provide an ideal microclimate for overwintering monarchs—if it’s too cold, they freeze to death; too warm and they burn up their fat reserves and perish. After clustering on trees for four to five months and then mating, these same insects fly northward toward Texas. Subsequent generations spread out over two million square miles, ranging from Minnesota to Maine, Manitoba to Mississippi, in their search for milkweeds on which to lay their eggs. Offspring keep pushing north until shorter days and falling temperatures cue the hatch of the long-lived super-generation that undertakes the three-thousand-mile journey to Mexico. Whereas summer monarchs only live about a month, migrators can live up to eight months, and it takes three or four generations of varying lengths to complete this annual migratory cycle.

Four generations of monarch butterflies gradually migrate northward, laying eggs on milkweed plants as they go, birthing successive broods that continue the northward journey. The final “super-generation,” which will live about eight months, migrates all the way back to central Mexico, a place they have never been before. (Courtesy of Monarch Watch)

If you’re familiar with the discovery story of the monarch butterflies’ overwintering sites in Mexico, Emilio’s father Valentín Velázquez is not a name you would have encountered. In fact, nobody native to the area where the monarchs roost appears in any of the official accounts of this advance in scientific understanding. Outsiders take center stage in both the 1976 issue of National Geographic magazine that broke the story and the 2012 IMAX film Flight of the Butterflies, which dramatized these events. That’s not to say that these accounts are not true, just that they are partial: a very different narrative about what happened and why it mattered emerges if you listen to the monarchs’ Mexican neighbors.

Before turning to their stories, we offer a brief sketch of the standard version. In January 1975, a Mexican citizen-scientist named Catalina Aguado and her American husband, Kenneth Brugger, encountered millions of monarchs clinging to the trees below the summit of Cerro Pelón, a mountain on the border of Michoacán and the State of Mexico. The couple had been searching for a colony for more than two years at the behest of the Insect Migration Association, a citizen-science brigade organized by Fred and Norah Urquhart, two Canadian researchers at the University of Toronto. The Urquharts had been investigating the monarch migration since 1937 but were unable to conclusively determine where the winged wanderer overwintered. A few days later, Aguado and Brugger recovered a tagged monarch at another colony, Sierra Chincua, which they sent to the Urquharts. A label the size of a postage stamp, glued to the butterfly’s wing, had been attached by one of the Urquharts’ volunteers four months prior in Missouri. Tagging data proved that the monarchs that flittered across the United States and Canada every spring and summer were the same ones that clustered every winter in Mexico. In 1976, Fred Urquhart announced this finding to the world in National Geographic. Aguado, despite being pictured on the cover, was mentioned only once in the text: “Ken Brugger doubled his field capacity by marrying a bright and delightful Mexican, Cathy.” This slight marked the beginning of the erasure of ordinary Mexicans from monarch history.2

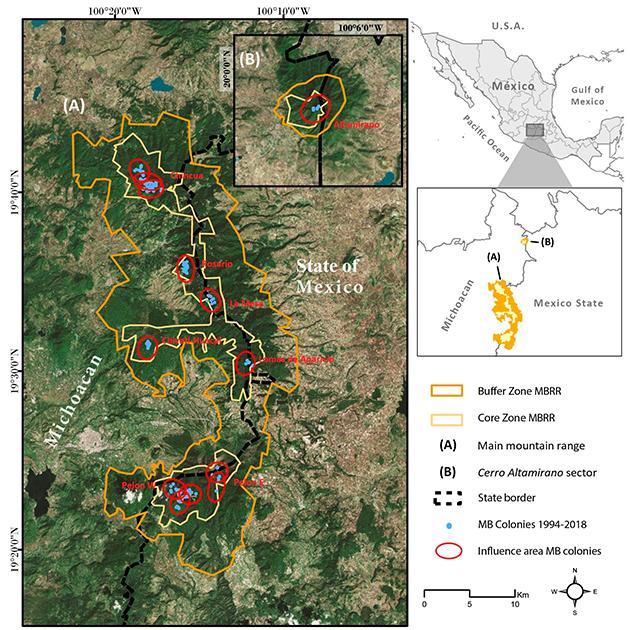

Exclusion also characterizes subsequent accounts of monarch conservation in Mexico. In 1980, President José López Portillo declared a vague protected area for overwintering monarchs, even though fifty ejido and indigenous communities held ownership of these lands, dating back to the post-revolution reforms of the 1930s. Local people continued to exploit forest resources despite this decree. After scientists with the International Union of the Conservation of Nature listed the migration as an “endangered phenomenon” in 1983, famed poet Homero Aridjis organized artists and intellectuals into Grupo de los Cien (Group of 100) to lobby the Mexican federal government for stricter wildlife protections. In 1986, President Miguel de la Madrid issued another decree implementing formal boundaries and regulations for a 60-square-mile federal reserve (later named the Reserva de la Biosfera Mariposa Monarca). In 2000, the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve was expanded to 217 square miles, enlarging “core zones” where extractive activities were forbidden and “buffer zones” where natural resource use required a government permit. Nevertheless, clandestine logging proceeded, even accelerated, as land-reform beneficiaries (ejidatarios) continued to assert their rights to the forest. In 2008, UNESCO declared the butterfly sanctuary a world heritage site to bring attention to this fragile ecosystem of high cultural and biological importance.3

The Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve straddles the states of Michoacán and Mexico. The yellow lines mark the “core zones,” where the butterflies roost and extraction is forbidden. The orange lines mark the “buffer zones,” where natural resource use is regulated. The Cerro Pelón colony, where CEPANAF foresters work, is the southernmost location. (Courtesy of M. Isabel Ramírez, Centro de Investigaciones en Geografía Ambiental-Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México)

The conventional histories about the finding of the colonies, and the cascade of bureaucratic changes intended to protect them, emphasize the actions of political and scientific elites. Yet the people who have done and continue to do the labor of conservation, as well as the organizations that employ them, are largely absent from these narratives. To provide a more complete picture of monarch conservation history in Mexico and the challenges it faces, we conducted oral history interviews with two generations of foresters working in the Cerro Pelón Monarch Butterfly Sanctuary. We interviewed three rangers who worked for Comisión Estatal de Parques Naturales y de la Fauna (CEPANAF, State Commission of Natural Parks and Wildlife) from the late 1970s until their retirement in 2014; two of them are highlighted below. We also interviewed a CEPANAF ranger who took over the work, along with four of the forest guardians from the nonprofit he helped found, Butterflies & Their People AC. Taken together, these accounts, now translated and donated to the Forest History Society archives, offer a bottom-up view of the importance of involving local communities in the conservation of their forests.

From Hacienda to Ejido

Leonel Moreno Espinoza, in 2020. Leonel and four other local men from Macheros secured positions as foresters for Comisión Estatal de Parques Naturales y de la Fauna in the mid-1970s. Photo by Ellen Sharp.

Leonel Moreno Espinoza was a hard man to track down for an interview. Whenever we stopped by his sprawling multigenerational household, Don Leonel was busy: mucking out his sheep pen, planting corn, shopping for his corner store. When we finally did catch up with him, he credited his high energy and longevity—he turns eighty-two in 2020, “God willing”—to his forester job. “We were in love with the forest. I think that all the time we spent in the forest has lengthened our lives, because I tell you, I’m getting up there and to date, I still feel good.”4

Leonel initiated our conversation by reminding us of the history memorialized in the place names that surrounded us. Before the Mexican Revolution began in 1910, Cerro Pelón was controlled by the Hacienda San Bartolo, a large estate whose owners had built railroad tracks deep into the forest to extract what must have been massive amounts of timber. What workers couldn’t reach by train, they dragged out with draft animals. Macheros, the village at the entrance to the Cerro Pelón sanctuary, is where they kept their horses, a machero being a corral or stable.

Leonel’s grandmother came from another town to look for work on the hacienda after her husband died. Soon her three young children were working on the hacienda as well. When they grew up, they took up arms against the system of debt peonage and then petitioned the government for the communally held land that formed the basis of an ejido. In 1937, a year before Leonel was born, the first wave of applicants received rights for three thousand acres to create Ejido El Capulín. Macheros is one of five villages within this ejido. Leonel recounted:

When the hacienda later ended, my father and my uncle and other people were the initiators of the ejido, they were among those who fought for them to give them their land, they said that they had suffered a lot.… They spent days walking to Mexico City or Toluca for the efforts of the ejido and yes, thank God, they managed to get the government to give them the land, and since then we stayed here, we were born here, and here we are.5

Stories about the struggle for a more just system of landownership were something that Leonel learned from his jefe, or boss, as people here affectionately refer to their parents. Leonel represents one of the village’s last living links to first-hand knowledge of this legacy, one that his grandchildren proudly claim as well. People here fought to reap the benefits of their labor and land, and a bloody ten-year revolution ended with the creation of a more equitable system—at least until the butterflies were discovered and some of these rights were taken from them.6

“Discovering” the Monarch Colony

During his 1940s boyhood, Leonel heard elders talk about the origins of the monarch butterflies. “Some older folks said that butterflies were born from the oyamel seeds, others said that there was a cave in Cerro Pelón and that butterflies came from there,” Leonel recalled.7 People may not have known exactly where the monarchs came from, but they certainly saw a lot of them every winter. In an agricultural economy, children herded sheep and cattle on lands farmed by the ejidatarios—properties later expropriated to form the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve. As Leonel explained:

We knew about the butterflies since we were boys, up there in El Jaral, because men who lived here had land there…. And there is a spring that we called Agua del Jaral, that the landholders diverted into a canal. The canal was filled with water, then the butterflies went down into the water and we played with them and even killed them…. There were so many butterflies hanging out there. But in all that time as a child seeing butterflies, I never went to the colony, never.8

A cousin, Elidió Moreno de Jesús, looked after animals with Leonel. During our interview, Patricio Moreno asked his uncle when he first saw the colony in the 1970s. Elidió brushed off the question by saying he’d already seen them at El Jaral when he was young: “When we were herding cattle, we would go into the forest to look for the cows that wandered off so we could get the herd back together … and there in the forest the branches were loaded with [butterflies].”9

Elidió hadn’t mentioned this sighting to Leonel, who didn’t see the colony until he was an adult and outsiders began asking about it. Leonel sounded a bit frustrated when he described missing out on discovering the colony by a day. According to Leonel, “two Canadians,” perhaps Fred and Norah Urquhart, met with the governor of the State of Mexico, who then put his friend, Jesús Ávila, in charge of locating the colony.

Don Jesús came to us and said, “Go look for the butterflies, it’s urgent.” … Valentín and I went … to the meadow [El Llano de Tres Gobernadores] and in the meadow it was like a cloud of butterflies flying from one side to the other. And from there we walked into the forest to look for them and found nothing, so we crossed over to Carditos where there was also a swarm of butterflies, but we did not find [the colony] because it started … raining really hard, and when it rains the butterflies settle down and stop flying. We sat there under a piece of rubber that I’d brought … then the rain stopped, and we no longer saw any butterflies. It was late and we went home, and the next day Elidió and Valentín went back … and they found [the colony] right there where we’d been stopped by the rain, there they were.10

CEPANAF ranger Valentín Velázquez, taken around 1977. He helped identify the location of one of the monarch colonies. (Courtesy of Maraleen Manos-Jones)

Valentín Velázquez was killed in a brawl in 1981, when his son Emilio was only six years old. According to family lore, it was his late father who found the butterflies and provided conclusive proof of the colony’s existence. As Emilio explained it,

A man named Jesús Ávila, he sent my father to look for them. I think he paid him for the days that he went looking for them, and he found them. He was the one who discovered them here on Cerro Pelón. Yes, he was the first and then later he brought some down in bags. He made some holes for them [in the bags] and he came down [the mountain]. I don’t know how many [butterflies], because I don’t remember how many, but I do remember he brought down several bags.

Of living butterflies?

Yes, for Don Jesús Ávila, to prove that they had been found.11

Emilio’s family credits his father with the discovery, but others highlight the role of Jesús Ávila. Depending on whom you ask, Jesús Ávila Montes de Oca was either an ex-hacendado (estate owner) himself or closely descended from them. People describe him as big, light-skinned, used to commanding the labor of others and given to wearing a pith helmet while doing so. He was from the county seat, Donato Guerra, and he organized hunting parties and brought them to Cerro Pelón through Macheros, where he hired local men as guides. Leonel, Elidió, and Valentín helped “Don Chucho,” as they called him, hunt deer. During one of these excursions, Ávila remembered first seeing a tagged monarch, but he declined to contact the Urquharts. Whether or not he can claim the discovery, he is fondly remembered in Macheros for another reason.12

The Ranger Jobs

According to our interviews, Jesús Ávila sent local men from Macheros to search for the monarch butterfly colonies and Velázquez discovered one of them at Cerro Pelón. (Courtesy of Maraleen Manos-Jones)

Around 1977, perhaps earlier, Jesús Ávila used his political connections in the State of Mexico to secure work for the men from Macheros as guardabosques (forest rangers), through what eventually became CEPANAF. With enthusiasm, Don Leonel described the day that changed his life:

On December 12, which is the feast day of the Virgin [of Guadalupe] in El Capulín, my family and I went to the fiesta but we came home when the procession of the Virgin was finished.… And Don Jesús arrived late and said to me, “I’m here because I need three people. You are one, and who else do you want us to take?”

And I told him Elidió was there at home, he hadn’t gone to the party. So, I said to him: “Well, let it be Elidió.”

“And who else?” I told him Valentín. “But where is he?” Valentín was still hanging out at the party. “Where is he?”

Margaro [a neighbor] happened to be walking by and I said to him, “We need Valentín, go find him and bring him back.” And Margaro took off running to find him in El Capulín and he brought him back and Valentín was in his right mind, not in his cups yet.

And once he got there, Don Jesús says, “Let’s see. Take a bath and fix yourselves up. Tonight, you’re going to stay at my place, not with your women. I need you!”

He didn’t take us to Toluca, he took us to Mexico City… We went to what at the time was called the Secretary of Agriculture and Water Resources…. That was the place, and that was where they wrote down the names of all four of us, including Don Jesús, because he was in charge of us, and they signed us up, and, how cool—the job was taking care of the butterflies.13

Valentín’s eldest son briefly took over his job after his death but was fired after he got into a fight with men from the Michoacán side of the sanctuary. Elidió’s younger brother, Melquiades Moreno de Jesús, joined CEPANAF in 1982. These CEPANAF rangers patrolled the Cerro Pelón butterfly colony on the State of Mexico side of the monarch reserve for some forty years. Not only did their near-constant monitoring improve forest health, which was visibly more intact than on the Michoacán side, but a steady paycheck also pulled their families out of poverty. These three men were among a handful of individuals in an ejido numbering two thousand people who enjoyed full-time work with paid vacation, health care, and a government pension. Although these kinds of jobs are now a rarity anywhere, they were even more unusual in rural Mexico, where fifty-eight percent of the population is informally employed and nearly half live below the poverty line.14

Who’s in Charge?

Throughout these years, designations for what became the protected area were in flux. When the CEPANAF rangers started work, Cerro Pelón wasn’t part of the federal reserve, but once it became part of that system, they continued their jobs. As explained above, the protected area came into being in 1986, took over more land in 2000, and became part of UNESCO’s Patrimony of Humanity in 2008. When we asked the rangers about how these administrative changes affected their work life, we got blank looks: “Could you repeat the question?” From their perspective, top-down measures minimally affected on-the-ground management.

Other agencies rarely dropped by, but when they did, the CEPANAF workers sometimes came into conflict with them. Elidió told a story of arguing with officials from Procuraduría Federal para la Protección al Ambiente (PROFEPA, Federal Environmental Protection Agency, or the forest police) as the rangers were getting ready to build a firebreak. Elidió recalled:

Those aggressive PROFEPA guys came with their notebook, and I got scared. I thought those bastards were going to denounce us. They were writing things down and asking, “Why are you doing that?” [I told them] because we don’t want the forest to burn down, and if the fire reaches here, this part will burn. What are we going to put it out with? With a hat? With a branch?15

The lack of governmental cooperation has made the biosphere reserve a jurisdictional morass for managers. It’s an ongoing problem: in early 2020, agents of the new environmental police interrogated the Butterflies & Their People guardians as if they were illegal loggers when they met them on the mountain.

Fighting illegal logging had been a constant on Cerro Pelón. The first generation of rangers saw their jurisdiction as stopping where the state line ended along the crest of the mountain, even though the colony alternated sides of this border every season. They were all from the State of Mexico, and although they worked for a state agency, they didn’t have the authority to fine or arrest people for tree cutting. All they could do was talk to the loggers and make reports to their superiors. Will tried to follow up on these records, but the files had not been kept. There is no accurate record of the logging that did take place, or much credit given to the CEPANAF rangers who spent their lives trying to prevent it.

Organizational Changes

Now there’s a new generation of CEPANAF rangers. All three men, including the ones we interviewed, had inherited the positions from their fathers—a fraught transition in families with many sons. And once they had their jobs, their agency sometimes seemed less than committed to keeping the rangers on Cerro Pelón, a sanctuary that was technically the responsibility of other agencies. In summer of 2017, the new team was sent to work in another CEPANAF installation. Left unpatrolled, the forest was hit hard by loggers, who cut down more than a hundred trees in the core protected area. I (Ellen) launched a Change.org petition, which succeeded in sending the rangers back to their former territory.16 In our negotiation of their return, the rangers for the first time were in direct communication with Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas (CONANP, National Commission on Protected Natural Areas), the federal entity overseeing the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve. CONANP has the authority to call in the police when there is logging. The rangers looked forward to better working relations and more rapid responses to their reports.

Another turning point came when additional workers joined the rangers on Cerro Pelón. Butterflies & Their People AC was inspired by the CEPANAF model: these jobs made a difference for their families and for forest health. I met a lot of Canadians and Americans involved in monarch conservation through my ecotourism business who cared deeply about the future of the migration. Overwintering numbers have plummeted precipitously since monitoring began in the 1990s. Deforestation in Mexico is one of the factors behind this population decline. Along with Joel and Patricio Moreno, both sons of a CEPANAF ranger, I established an asociación civil (nonprofit) in fall of 2017 to look for funds in support of the project. Three years later, we had six full-time workers, half from the State of Mexico and half from Michoacán, making it the first time that people from that side of the sanctuary had been included in forest protection.17

Butterflies & Their People guardians José Carmen Contreras, Joaquin Moreno, and Emilio Velázquez with supervisor Patricio Moreno (seated in hat) in La Lagunita on Cerro Pelón in May 2020. Photo by Ellen Sharp.

CEPANAF ranger Patricio “Pato” Moreno Rojas started working on Cerro Pelón in fall of 2014. When asked what it meant to him to have the same conservation job as his father Melquiades, Pato beamed.

It is an honor because since I was little, I remember that he always took me with him. Almost right after I was born my dad began to work in what was forest protection. … It was nice to follow him, and now you can imagine how it was to be with him, that is, how we were in the forest together, because that fills me with pride and following what he did is the best, continuing to protect the forest.18

Before securing the CEPANAF position, the newly married Pato had shuffled from one job to the next and struggled to get together enough money to move out of his parents’ house. “Now, the way one lives is very different with the income,” he remarked. “It’s not much, but it’s not little and it’s enough to have a good life, especially for being more stable.”19 Pato now lives next door to his parents in a tidy two-story house with his wife and kids.

He spends most of his time on regular patrols of the Cerro Pelón sanctuary. Other duties include maintaining trails, building firebreaks, regulating tourist use, and managing the forest guardians employed through Butterflies & Their People. Pato also paints, films, and photographs the migration; his images have attracted tens of thousands of followers to his Facebook profile. When asked about his job, Pato said, “Oh, the best part is being in the forest. It is the best thing to have a connection with nature. And then being with the butterflies. You imagine the butterfly forest is something unique, it is something special for us.”20 The worst part? He described encountering illegal logging of the butterfly trees: “You go into the forest and see the trees and you think of them as friends who are part of you, then to see a tree that is cut down is very difficult and it’s sad seeing the forest cut down.”21

The Persistence of Illegal Logging

Even though park regulations outlaw timber extraction inside core zones, logging in the monarch reserve remains a problem. Using repeat aerial photographs of the forest on the Michoacán side, scientists have documented that forty-four percent of the habitat was degraded between 1971 and 1999. Thinning the forest removes a protective blanket over the monarchs, exposing them to greater weather extremes and thus higher mortality. Winter storms in 1981, 1992, 2001, 2002, 2004, and 2016 have led to mass die-offs of the colonies, and the number of recorded overwintering sites has fallen from thirty to a dozen over the last forty years.22

Conserving a closed canopy of intact forest is crucial to monarch survival. Pato believed that the presence of rangers had made a difference at Cerro Pelón:

In the case of what is CEPANAF’s jurisdiction in the State of Mexico, it has helped a lot. Michoacán’s area is clearly marked [by deforestation] compared with the State of Mexico, and that is thanks to the oversight that has been carried out since the butterfly was discovered, because the forests are in much better condition and they are still much better. So, I think that if there were surveillance on both sides, forest conditions would improve.23

When asked what he does when he encounters illegal logging, Pato said,

Even if we find someone, we do not have the authority to detain them, just to report them, and we do it to the agencies that are responsible for following the complaint process for the case. We can’t make the complaint, just the report, but they should follow it up as an official complaint about logging.

Although some reports are not taken up by higher authorities, Pato believed that having a physical presence on the landscape was the most effective deterrent. For the past three years, rangers have been coordinating their work with Butterflies & Their People AC to enhance forest protection for this fragile overwintering habitat. “Above all,” observed Pato, “just go to those areas that are affected, spend more time there so that [logging] decreases. That’s a way we can help the forest.”24

Pato viewed the persistence of clandestine logging as a symptom of economic desperation: timber provides cash. Osvaldo Esquivel Maya, a Butterflies & Their People guardian who lives in Comunidad Indígena Nicolás Romero on the Michoacán side of Cerro Pelón, echoed his assessment: “Sometimes it’s easy to cut down a tree and take it to sell, but the reason for this is there are no jobs. That’s why people do logging.”25

Recent clandestine logging near La Lagunita, core protected area, Cerro Pelón. Tree felling threatens the overwintering habitat of monarch butterflies. Photo by Ellen Sharp.

Retired ranger Elidió Moreno admitted that before he got the CEPANAF job, he used to chop down trees and take them to the nearby city of Zitácuaro to sell for firewood. Now that the forests are part of a protected area, people can no longer openly sell wood on the street. These days, “you already have your contacts,” Emilio Velázquez explained. “Then when I decide I’m going to cut a tree, I know where I’m going to sell it and what price I’ll get for it.”26 Buyers are rarely penalized in this transaction; it’s the poor people cutting and hauling wood out of the forest who risk running into the authorities. Emilio, who also used to be involved in illegal logging before working for Butterflies & Their People, recalled an unhappy day a decade ago when one of his logging crew members was caught with a downed tree and fined $80,000 MXN ($3,500 USD). He shook his head, sadly remembering how long this financial catastrophe set his family back: “We took out loans against our land titles, we sold what we had.” Emilio concluded, “Now I have a secure job and I will not cut down trees again because it’s very dangerous.”27

When work is available, less pressure is placed on the forest. José Carmen Contreras Meza, a Butterflies & Their People guardian from Ejido Nicolás Romero, recounted how their former commissioner got community funding for three hundred temporary forest jobs. Logging, José Carmen said, “had diminished a lot because [Commissioner Darío] gave work to … all who came to ask for work. He did not discriminate against anyone and he was the one who stopped logging. But the commissioners who came along later no longer followed suit, nothing more [was given].”28 Either the next local political leader failed to apply for funds or the money was no longer available. Some nonprofit organizations operating within the monarch reserve do offer workshops on economic alternatives to logging, such as trout aquaculture or handcraft production; others make small annual payments to local people for conserved forest.29 But it’s inadequate, given the widespread economic need. The result of this underemployment has been “disorder,” to use José Carmen’s word, in the part of the forest near his ejido, where people have cut down dozens of oyamel firs on the path that leads to the butterfly colony at Carditos.30

In the past, administrators of this protected area have blamed “organized crime” for the logging. The workers who spend their days on the mountain find this assertion absurd. CEPANAF rangers know that loggers are not dangerous, just desperate—and young. “Most [are] twelve- or fourteen-year-old kids who are no longer going to school,” Pato said.

They are not [dangerous] because we have sometimes had experiences of finding some and, no, they are simply scared. When you get there, they are scared and we’re wearing our uniform, but it is not a police uniform—it’s a uniform of park guards—but people are scared. We know that they are unarmed. There is no organized crime in this place.31

The undemocratic structure of land ownership is another obstacle to effective, sustained forest conservation. Although the ejido system vastly improved the lives of the landless peasants who toiled on the haciendas, the land reform was still based on an unequal distribution of resources. The title of ejiditario became an inherited position handed down from father to youngest son. In Ejido El Capulín, only 12 percent of the residents are ejidatarios, a title that gives them the right to participate in local governance and receive government aid, including the annual financial incentive that’s intended to stop illegal logging of the protected area. Everyone else is excluded from these benefits. Effective forest conservation cannot happen without real economic justice.

Love and Hunger

You can fall in love with a forest, like Leonel said. You can toddle after your dad like young Pato and grow up to feel the loss of a tree as keenly as the death of a friend. But loving nature is not a given. Like the butterflies every winter, love needs the right conditions to grow. The CEPANAF rangers had a job that took care of them, and so they took care of the forest. Butterflies & Their People has been trying to include more of the monarchs’ Mexican neighbors in this reciprocal relationship. But as Emilio admitted, back when he was working as a horse handler, leading tourists up the mountain, he never bothered to hike the few extra feet to see the butterfly colony. He was tired after walking six kilometers up rocky switchback trails. “But now that I’ve been here, I never get tired of seeing them … Every day is different.” He smiled as he went on to describe what happens when the sun heats the colony up and thousands of monarchs fly forth from their tree all at once in an explosion. “We have missed very beautiful moments.”32

Emilio and the other rangers are up against is what one of his brothers once said: “It’s hard to give a fuck about butterflies when you’re hungry.”33 Hunger means looking around to see what you can take to sell, instead of thinking about the future, or appreciating a present moment made beautiful by a burst of butterflies.

The coronavirus pandemic that began in the spring of 2020 puts more pressure on forest resources. Many workers have been laid off and sent back to their villages; and we’re already seeing an increase in logging on Cerro Pelón. While Patricio was pleased by the rangers’ newfound connection to CONANP, that agency just saw its federal appropriation cut by seventy-five percent.34 Their affiliated community development program, the one whose project José Carmen credited with halting illegal logging in his community, has been eliminated. An austerity budget puts more pressure on Butterflies & Their People and other nonprofits to fill the conservation holes left by a federal government. Yet the governing body of Ejido El Capulín has decided to close the Cerro Pelón Monarch Butterfly Sanctuary to visitors this upcoming season, effectively shutting down the ecotourism industry that employed over a hundred local people and helped fund this nonprofit in particular. Donations came from sightseers to Cerro Pelón, mostly guests who arrived from far away, and we’re unlikely to see that level of transnational travel again anytime soon. Like the CEPANAF precedent, Butterflies & Their People is doing everything within its power to replace hunger with love.

About the Authors

Ellen Sharp is the cofounder and director of Butterflies and Their People AC, and the co-owner of JM Butterfly B&B, an ecotourism business in Macheros. She holds a PhD in cultural anthropology from the University of California–Los Angeles. Visit www.butterfliesandtheirpeople.org for information about the nonprofit’s work.

Will Wright is a PhD candidate in history at Montana State University–Bozeman and is working on a dissertation about transnational conservation, including the monarch migration. He was also the 2019 corecipient of the Forest History Society’s Rosenberry Graduate Fellowship, which supported this work.

NOTES

1. Emilio Velázquez Moreno, interview by Ellen Sharp, translation by Will Wright, May 9, 2020, Oral History Collection, Forest History Society, Durham, North Carolina (hereafter OH-FHS).

2. Fred A. Urquhart, “Found at Last: The Monarch’s Winter Home,” National Geographic, August 1976, 161–74. For the history of the migration discovery, see Frederick A. Urquhart, The Monarch Butterfly: International Traveler (Chicago: Nelson Hall, 1987); Lincoln P. Brower, “Understanding and Misunderstanding the Migration of the Monarch Butterfly (Nymphalidae) in North America, 1857–1995,” Journal of the Lepidopterists’ Society 49 (1995): 304–85; Sue Halpern, Four Wings and a Prayer: Caught in the Mystery of the Monarch Butterfly (New York: Pantheon Books, 2001); Monika Maeckle, “Founder of the Monarch Butterfly Roosting Sites in Mexico Lives a Quiet Life in Austin, Texas,” Texas Butterfly Ranch, July 10, 2012, https://texasbutterflyranch.com/2012/07/10/founder-of-the-monarch-butterfly-roosting-sites-in-mexico-lives-a-quiet-life-in-austin-texas/.

3. Diario Oficial (April 9, 1980); Susan W. Wells, Robert M. Pyle, and N. Mark Collins, IUCN Invertebrate Red Data Book (Gland, Switzerland: International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, 1983), 463–66; Homero Aridjis and Betty Ferber, Noticias de la Tierra (Mexico City: Debate, 2012); Diario Oficial (October 9, 1986); Diario Oficial (November 10, 2000); “Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve,” UNESCO, https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1290/.

4. José Leonel Moreno Espinoza, interview by Patricio Moreno Rojas and Ellen Sharp, translation by Will Wright, May 22, 2020, OH-FHS.

5. Espinoza interview.

6. “Resolución en el expediente de ampliación de ejidos al poblado El Capulín, Estado de México,” Diario Oficial (June 19, 1937): 11–13.

7. Espinoza interview.

8. Espinoza interview.

9. Elidió Moreno de Jesús, interview by Patricio Moreno Rojas and Ellen Sharp, translation by Will Wright, April 27, 2020, OH-FHS.

10. de Jesús interview.

11. Moreno interview.

12. Other than the CEPANAF interviews, the only other mention of Ávila is in a children’s book by Fernando Ortiz Monasterio and Valentina Ortiz Monasterio Garza, Mariposa Monarca: Vuelo de Papel (Coyoacán: Centro de Información y Desarrollo de la Comunicación y la Literatura Infantiles, 1987), 51.

13. Espinoza interview.

14. “Poverty headcount ratio at national poverty lines (% of population)—Mexico,” World Bank Data, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.NAHC?locations=MX. For studies on community-based conservation at the monarch reserve, see Leticia Merino Pérez and Mariana Hernández Apolinar, “Destrucción de instituciones comunitarias y deterioro de los bosques en la Reserva de la Biosfera Mariposa Monarca, Michoacán, México,” Revista Mexicana de Sociología 66 (2004): 261–308; Catherine M. Tucker, “Community Institutions and Forest Management in Mexico’s Monarch Butterfly Reserve,” Society and Natural Resources 17 (2004): 568–87.

15. de Jesús interview.

16. Monika Maeckle, “Success! Petition spurs rangers’ reinstatement at Monarch butterfly roosting forest,” Texas Butterfly Ranch, https://texasbutterflyranch.com/2017/07/10/success-petition-spurs-rangers-reinstatement-at-monarch-butterfly-roosting-forest/.

17. “Monarch Population Status,” Monarch Watch, https://monarchwatch.org/blog/2020/03/13/monarch-population-status-42/.

18. Patricio Moreno Rojas, interview by Ellen Sharp, translation by Will Wright, 7 April 2020, OH-FHS.

19. Rojas interview.

20. Rojas interview.

21. Rojas interview.

22. Lincoln P. Brower et al., “Quantitative Changes in Forest Quality in a Principal Overwintering Area of the Monarch Butterfly in Mexico, 1971–1999,” Conservation Biology 16 (2002): 346–59; Lincoln P. Brower et al., “Butterfly Mortality and Salvage Logging from the March 2016 Storm in the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve in Mexico,” American Entomologist 36 (2017): 151–64; Javier de la Maza E. and William H. Calvert, “Investigations of Possible Monarch Butterfly Overwintering Areas in Central and Southeastern Mexico,” in Biology and Conservation of the Monarch Butterfly, eds. Stephen B. Malcom and Myron P. Zalucki (Los Angeles: Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, 1993), 295–98.

23. Rojas interview.

24. Rojas interview.

25. Osvaldo Esquivel Maya, interview by Ellen Sharp, translation by Will Wright, May 9, 2020, OH-FHS.

26. Moreno interview.

27. Moreno interview.

28. José Carmen Contreras Meza, interview by Ellen Sharp, translation by Will Wright, May 9, 2020, OH-FHS.

29. Sjoerd van der Meer, “The Butterfly Effect: Butterflies, Forest Conservation, and Conflicts in the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve (Mexico),” (Master’s thesis, Wageningen University, 2007).

30. The “disorder” that José Carmen references can be seen in the reporting “Illegal Logging Inside Mexico Monarch Butterfly Sanctuary,” Voice of America News, https://www.voanews.com/episode/voa-films-illegal-logging-inside-mexico-monarch-butterfly-sanctuary-4273441.

31. Rojas interview.

32. Moreno interview.

33. As quoted in Ellen Sharp, “Who Gets to Be a Citizen-Scientist? Democratizing Monarch Studies to Save the Migration,” https://ellensharp.com/who-gets-to-be-a-citizen-scientist-e7d52a6239d2/.

34. “Recorte del 75% a las Áreas Naturales Protegidas tiene en inoperancia la CONANP,” Reporte Indigo, July 4, 2020, https://www.reporteindigo.com/reporte/recorte-del-75-a-las-areas-naturales-protegidas-tiene-en-inoperancia-a-la-conanp/; Tania Islas Weinstein and Milena Ang, “AMLO Can’t Fight Poverty through Austerity,” Jacobin, July 28, 2020, https://www.jacobinmag.com/2020/07/amlo-mexico-cultural-science-workers-coronavirus-austerity.