Rethinking Wilderness After The Wilderness Act

Have you ever been in an urban forest and had the feeling that you were off in the wild because you could no longer hear any cars? Did you find yourself on a river trail and felt as Emerson did when he wrote, “In the woods, is perpetual youth”? Or have you been in state park, turned on a trail and thought, “Geez, I’m in the wilderness!”? I can answer “yes” to all three of those questions. Here in the Durham area we have Duke Forest, the Eno River, and Umstead State Park, respectively, to explore and escape to. I find being in the forest—and what feels like wilderness in this increasingly urbanized region—is often restorative, if not transformative.

Scholars will tell you there are both legal and cultural constructs of wilderness. While Duke Forest, Eno River, and Umstead State Park are not, by legal definition, wilderness, such places do give a sense of being in wilderness. In many ways, it comes down to perception, to paraphrase William Cronon from his essay “The Trouble with Wilderness: Or Getting Back to the Wrong Nature.” These are places where I, too, experience what he calls “the sacred in nature”—places near my home.

Duke Forest, Umstead Park, and the Eno River, where this was taken, are very popular with the Durham running community. During the 2012 Eno River Race, I experienced both “the sacred in nature” and the profane as I forded the cold river.

Wilderness, in all its many constructs, was celebrated around the United States on September 3, 2014, when its supporters commemorated how the legal construct of wilderness has been protecting the cultural one for 50 years. It was on that date in 1964 that President Lyndon Johnson signed the Wilderness Act, which created the National Wilderness Preservation System, the most extensive system of protected wild lands in the United States. Since its signing, the law has continually inspired people to protect wilderness and enjoy it, too.

As someone who studies the history of forests and how humans interact with them for a living, I’ve been fortunate enough to spend time in and write about both legally designated wilderness areas in Montana and places that are wilderness areas in all but legal standing, like in Maine. So it’s more than a little ironic that as someone who enjoys running and hiking wooded trails, I’ve not visited any of North Carolina’s twelve federal wilderness areas. But it’s fine with me. I have Duke Forest, the Eno River, and Umstead Park, even though they aren’t on that list. It doesn’t alter my enjoyment of these places—if anything, it makes me appreciate them all the more because they remain wooded oases in this rapidly urbanizing area.

What these local places have in common with federal wilderness areas is how they came to be protected and cherished spaces. The history of each involves someone at some point looking at a landscape, whether it was abandoned agricultural fields in need of restoration (like Umstead) or a forested area in need of protection (like Joyce Kilmer-Slick Rock Wilderness in western North Carolina), and deciding that intervening on behalf of the public was a greater good for the land.

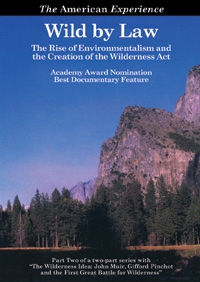

In the case of what would become federal wilderness areas, the effort was led in large part by Aldo Leopold, Bob Marshall, and Howard Zahniser, whose story is the focus of the Academy Award–nominated documentary film Wild By Law by Lawrence Hott and Diane Garey. All three men were leaders of the Wilderness Society, an organization formed in 1935 by Leopold, Marshall, and six other men to counter the rapid development of national parks for motorized recreation. The Wilderness Society supported projects like the Appalachian Trail but opposed others like the Blue Ridge Parkway because roadways like it were built at the expense of wilderness. (The tension between access to wilderness and protecting its integrity that led to the Society’s establishment is still a divisive issue today.) Zahniser, the executive secretary of the Society from 1945 until his death in 1964, carried forward the torch lit by Leopold and Marshall by writing the Wilderness Act and serving as its strongest advocate. The efforts of these and many other people have led to the protection of countless beautiful areas.

the focus of the Academy Award–nominated documentary film Wild By Law by Lawrence Hott and Diane Garey. All three men were leaders of the Wilderness Society, an organization formed in 1935 by Leopold, Marshall, and six other men to counter the rapid development of national parks for motorized recreation. The Wilderness Society supported projects like the Appalachian Trail but opposed others like the Blue Ridge Parkway because roadways like it were built at the expense of wilderness. (The tension between access to wilderness and protecting its integrity that led to the Society’s establishment is still a divisive issue today.) Zahniser, the executive secretary of the Society from 1945 until his death in 1964, carried forward the torch lit by Leopold and Marshall by writing the Wilderness Act and serving as its strongest advocate. The efforts of these and many other people have led to the protection of countless beautiful areas.

At just under an hour long, Wild By Law is a great introduction to this turning point in American history. Last September, a day after I addressed a community meeting in Wallace, Idaho, where people are struggling to make a living in a region surrounded by wilderness both protected and perceived, I hosted a screening of the film at the Durham County Library and a question-and-answer session. The discussions in both towns reminded me that passion runs high on the issue of wilderness protection, and that the issue is and will remain a complex one, but for good reasons. It means we still care.

I encourage you to seek out this film and any relevant history books (there are too many to list here) and then to reflect on 50 years of the Wilderness Act and all that it has done for what President Johnson called “the total relation between man and the world around him.” I also hope you’ll start visiting wilderness areas—however you wish to define them.

In large measure, wilderness is all a matter of perspective. Where do you think this was taken? On federal, state, or private land? In a designated wilderness area, or in my backyard? Does it matter?