Mission Mountains Primitive Area

The Mission Mountains Primitive Area's rugged scenery is unsurpassed anywhere in the Flathead National Forest.

Attention was drawn to this area comparatively early. The first organized exploration in this area was in September 1922 by a Northern Pacific Railway Company party that included O. D. Wheeler, a company writer, and Asahel Curtis, a noted photographer, often called "The Father of Rainier National Park." The company owned several thousand acres in this area, set aside for them under the 1864 railroad land grant. Forest Officer Theodore Shoemaker and Jack Clark accompanied the party on this first organized exploration of what is now the Mission Mountains Primitive Area.

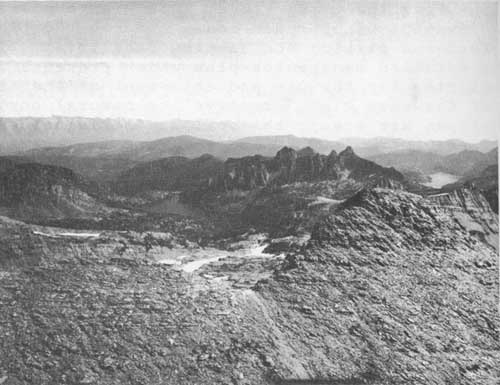

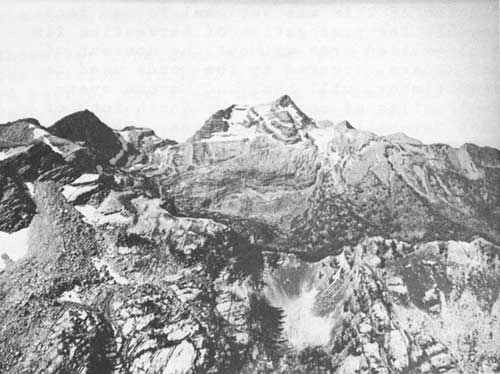

Many still and moving pictures were taken of the area's many lakes, waterfalls, and rugged scenery. Curtis called it one of the most, if not the most, scenic areas in the United States. The party was awed by the unique glacier sculpturing, the exposed bedrock terrain with evergreen trees striving to exist in the cracks and crevices. The soil mantle is extremely thin in these high alpine basins. Numerous permanent glaciers added to the line and color of the landscape.

Shoemaker conducted parties of the Montana mountaineers into the Missions in 1923 and 1924. In general, the parties covered most of the area, having advanced as far west as McDonald Peak which is west of the divide and is not within the area. Shoemaker made field notes of triangulations from various peaks and from these notes made the first map of this country. This high area has never been surveyed.

The Mission Mountains area was classified by Chief Forester R. Y. Stuart as a primitive area under regulation L-20 on October 31, 1931. The Northern Pacific Railway Company holds title to approximately 2,860 acres in six tracts in the eastern portion of the area. Negotiations are progressing with the railway company regarding exchanging National Forest land outside the primitive area boundary for the company's remaining holdings within the area. The Forest land inside the area consists of 73,340 acres plus the 2,860 acres of railroad land, which makes a total of over 76,000 acres.

At present the area is without adequate trails, although construction of a major, high-standard access trail from Glacier Creek northward is in progress. The present trail system does not lend itself to through travel. Until a through trail system is developed, the area will be more for hikers rather than parties using stock. Long-range plans include the improvement of approach roads and construction of adequate road-end parking and camping facilities. This area calls for a detailed management plan which presents a challenge to provide for the use and enjoyment of the area by people and, at the same time, preserve its natural environment. The slopes are steep; the soil mantle is thin and slow to heal. Also, there is very little grass for the grazing of pack stock.

The Forest Service was faced with a major decision after wind blew down about 1,000 acres of heavy timber in 1949. The Chief of the Forest Service authorized the salvage logging of blowdown timber in the primitive area to prevent a serious insect outbreak. But the logging operators were not interested in removing this timber, as it did not appear to be economically practical. By 1953, spruce bark beetles had built up to epidemic proportions in the blowdown areas and had spread to adjoining timber stands. Control logging was initiated, and the decision was made by the Chief of the Forest Service to log infested stands within the classified area adjacent to the boundary to prevent further spread of the epidemic. Eight road penetrations were made into the area by the Forest Service and the Northern Pacific Railway Company. After logging was completed, all roads were permanently blocked. About 2,000 acres were logged inside the boundary; 425 acres of this was National Forest land. The railway company has the prerogative of harvesting its timber inside the classified area without the consent of the Forest Service. Scars, created by the roads used to harvest the infested timber, will heal and become overgrown, as have the 14 miles of road up the North Fork of Sun River in the Bob Marshall Wilderness Area. This road was built nearly 80 years ago and was blocked off permanently by the building of the Gibson Dam in 1929.

The Mission Mountains Primitive Area is one of the last strongholds of the grizzly bear. This will perhaps be the grizzly bear's last retreat in the Flathead Forest. There are Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep in these mountains as well as a limited number of deer and elk and mountain goat. But the range for any grass-eating animal is limited due to the scarcity of soil. There are many lakes and waterfalls here. They are the most beautiful of any in the country. Gray Wolf Lake is the largest in the primitive area. High Park Lake covers 224 acres.

Visitor-use records for 1963 show that 2,370 people visited the primitive area. The average stay was 1-1/4 days. This suggests the interior of the area is not being used. The purpose of reserving this area was to preserve it for the use of man. It could be destroyed by overuse, if the area is interlaced with trails for stock use. This would encourage concentration around the limited camping spots and would drastically change the delicate ecology.

Looking east to High Park and Gray Wolf Lakes in the Mission Mountains Primitive Area.

Looking west toward McDonald Peak in the Mission Mountains Primitive Area.