Big Game Studies

While wildlife in the National Forest was always a concern of the early-day Rangers, wildlife studies were not started until the early 1920's.

Rangers traveled in pairs on snowshoe, usually with provisions and supplies on their backs. Cabins were few and far between; they made camp where night overtook them. These trips took from 2 to 3 weeks. Rangers counted the game in the areas they passed through and noted the condition of the wildlife and the condition of the winter range. They also checked for poaching or illegal trapping.

Dog teams were tried as a means of transporting supplies on these game-study trips. These dogs and sleds, however, did not prove to be very satisfactory because much of the travel was on steep side slopes and through the brush off the trail. This system was soon abandoned.

The building of more cabins added to the convenience of these trips. Until 1928, the Three Forks cabin was the only building on the Middle Fork. This one and one-half-story log cabin was built in 1910 by Allen Calbick. Lumber for the cabin was "whip-sawed" near the site. It was used until it was damaged by heavy snow in 1956.

These annual game trip reports showed that the game had increased beyond the carrying capacity of the winter range. Some of the Rangers who carried on these studies were A. E. Hutchinson, Al Austin, M. B. Mendenhall, Fred J. Neitzling, Tom Wiles, J. Roy Hutchinson, Henry Thol, and F. S. June (Forest employee). There may have been others I do not recall.

In the early 1930's, it was realized that the elk population was getting too large for the winter range. As a result, a more intensive study was initiated in the fall of 1933. Three crews were organized to spend the winter in the area to study the problem. One crew was headquartered at Big Prairie, one at Spotted Bear, and the third on the Middle Fork at Schafer.

The crews, with 6 months' supplies, went into these areas in early November and did not come out until late the following April. There were no plans for receiving fresh supplies or mail. Each crew carried a short-wave battery-powered radio for contacting the Supervisor's Office in Kalispell. Sometimes these radios worked. Crews heard from their families through the Forest Supervisor. I learned one day that I was the father of a baby daughter and that my wife and daughter were doing fine.

These men went through the usual dangers and hardships that go along with winter traveling on snowshoes in the mountains: snowslides, breaking through the ice in crossing rivers, short on rations, getting caught in storms, the cold weather (one time at Spotted Bear it was 57° below zero), and camping out in the snow. These were all taken in stride. Perhaps the fact that there was a national financial depression had something to do with the men taking all of this in stride.

Bob Casebeer (now on the Supervisor's staff of the Teton National Forest, Jackson, Wyoming) and I came into a cabin on our first trip in the winter of 1933 and found that someone—perhaps late fall hunters—had broken in and removed all our winter's supply of food. The only thing eatable was some yellow cornmeal in a dirty cloth sack. The meal was full of weevils. As it was late and a long distance to another cabin, we planned to stay that night. The more we searched, the hungrier we became. Finally I went outside, took a screen from the window, and used it to sift the weevils from the cornmeal. I put it on the stove and started to boil it. Bob, a young college student raised in Iowa, said, "I won't be able to eat that anyway after seeing all those creatures that came out of it." I said, "Well, I'll tell 'em where you passed out on the trail tomorrow." When the cornmeal was cooked, it smelled and tasted fine. We both ate our fill for supper, ate some more for breakfast, and carried the rest along with us for lunch on the trail. On other trips to this cabin that winter we carried our supplies.

These wildlife studies were continued, in much the same manner, for the next four winters. The situation was analyzed and steps were taken to do something about the overstocked winter elk range. Spotted Bear Game Preserve was eliminated in 1936. The Montana Fish & Game Department extended the 30-day season to 75 days. Odds did not favor such large numbers of game; the winter range was greatly reduced; and, of course, the elk herd was reduced principally by malnutrition.

It will take many years of intensive management before the winter range in the back areas will recover sufficiently for the elk population to increase to the levels of those of the late 1920's and early 1930's.

Following the four winters of intensive studies, yearly winter game patrol trips were made by the Forest Service through the area until 1941-42. Then, the Montana Fish & Game Department put crews in the area for the winter study.

In January and February of 1941, Ranger Leif Anderson and I went through the South Fork from Coram and, after taking side trips up the major drainages, came out 32 days later at Ovando. We traveled on skis. However, I don't recommend skis for travel on mountain trails; they are too dangerous. You are a long way from help if an accident should occur and, due to the increased speed on downhill trails, you are much more prone to accidents than when traveling by snowshoes.

Many Forest Service personnel were on these winter-game studies during the 1930's. Besides some of those mentioned earlier, a partial list follows as I remember them: Max Rogers, Jack Root, Ray Wedge, Carl Wetterstrom, Horace Godfrey, Les Darling, Albert Campbell, Joe Dzivi, Jelmar Wirkala, Ralph Thayer, Bill Gaffney, Bill Ibenthal, Norm Schappacher, Orville Sparrow, E. H. Buck, Richard Lynch, Bob Casebeer, "Casey" Streed, Jack Lillevig, Don Egan, and perhaps others I don't recall. I spent seven winters in this work in the South Fork.

In recent years, game census and range condition trend studies have been carried on by the Montana Fish and Game Department, mostly by the use of airplane and helicopter. The range conditions in the back country are not improving at this time. But range conditions will continue to improve in National Forest multiple use areas, such as in the lower South Fork and Swan Valley due to the harvest of timber.

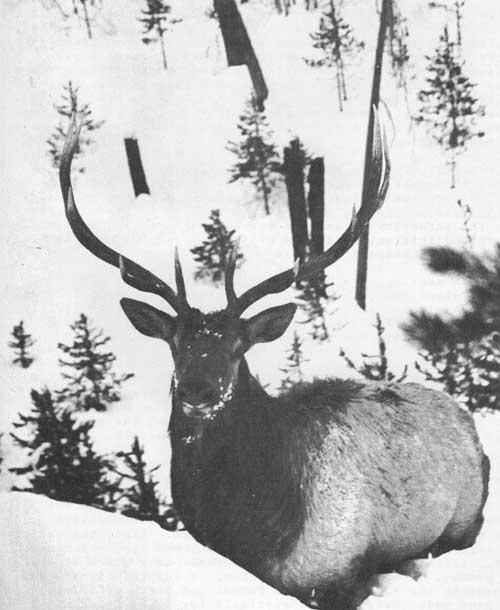

Elk in 40 inches of snow along Black Bear Creek. Photo taken by Charlie Shaw, March 1936.