Remembering Westvaco’s Christmas Classics Book Series

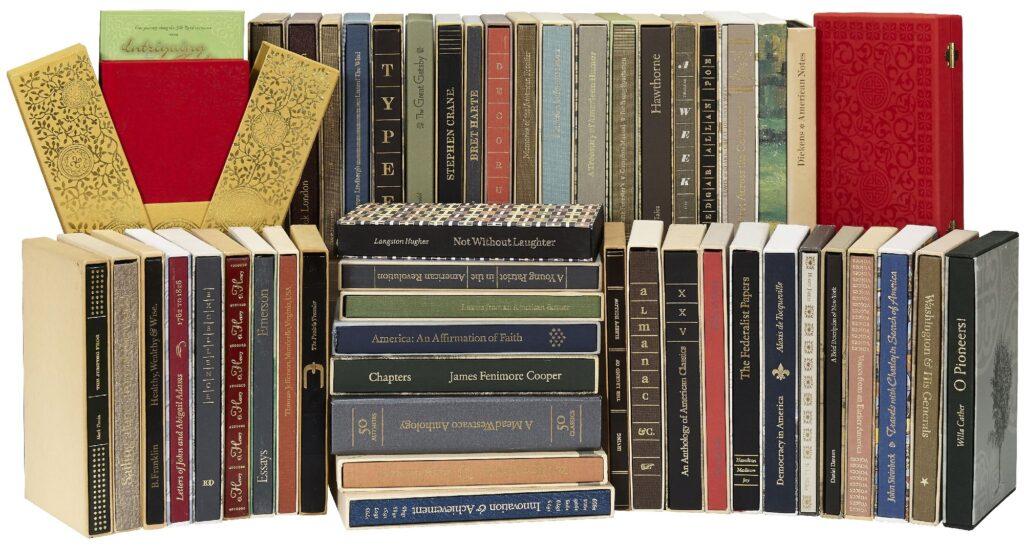

In 1958, the West Virginia Pulp and Paper Company started a holiday tradition that lasted half a century. Company CEO David Luke initiated the American Classics Series (also known as the Christmas Classics), published annually through 2007. According to Scott Wallinger, a former Westvaco company officer, “the Luke family favored being a producer of non-commodity products and focused on paper grades that others found more difficult to make.” In an era when books were on paper and held in personal libraries, Scott continued, the company was a leading producer of a wide array of quality, unique printing papers that it sold to most of the leading book publishing companies. Privately published, the book was presented to major publishing companies and their purchasing staffs at the end of the year to show the company’s wide-ranging capabilities. Officers of the paper company also received a copy. The name of the series changed when the company changed names: it became Westvaco American Classics Series in 1969 and the MeadWestvaco American Classics Series in 2002.

All aspects of production were managed in-house, overseen by the company's public relations department. They worked closely with leading graphic designers to make each book unique and representative of its time. J. Bradbury Thompson, one of the most influential graphic artists of the 20th century, was the lead designer for the first two decades. He had been in charge of the Westvaco Inspirations for Printers, the company’s influential arts journal since 1938. Distributed to some 35,000 agencies, museums, printers, schools, and universities, the journal was also produced to showcase the company's myriad capabilities.

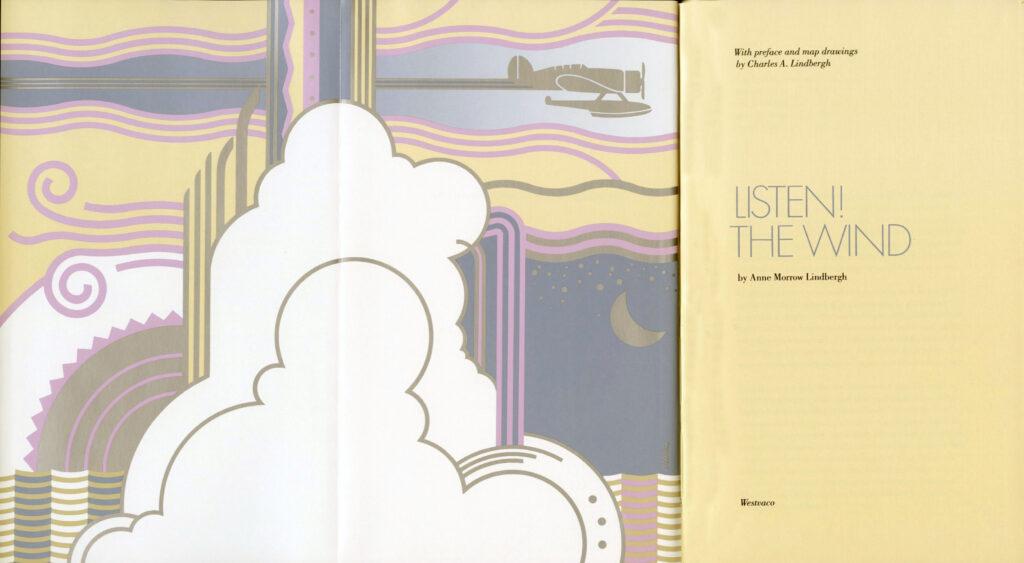

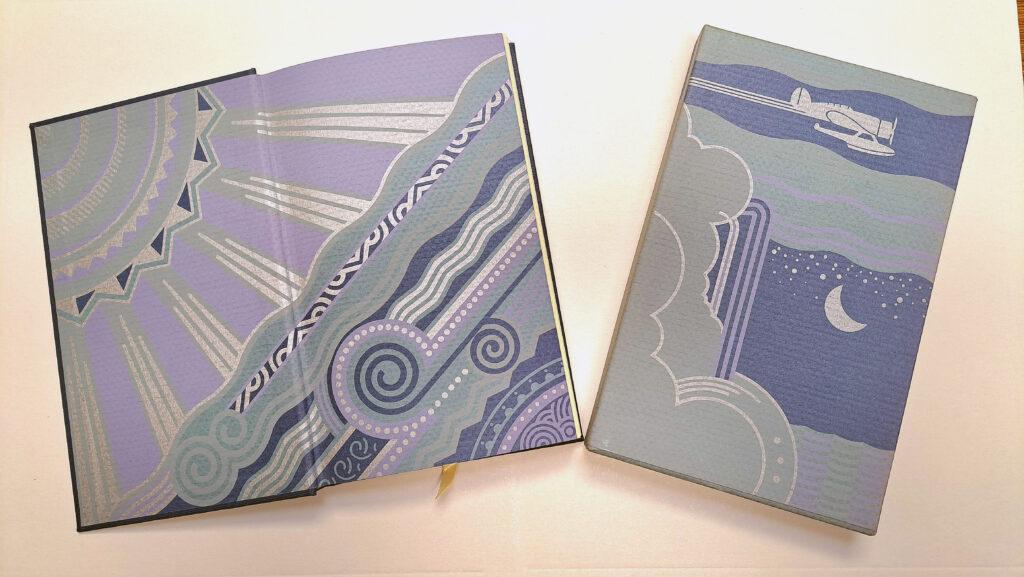

Each book listed the team members who put it together; the fonts used; and what papers were used and which plants manufactured each one. Each entry in the Christmas Classics series was carefully designed to use a type of printing paper that exemplified the paper of the era when the book was first published, thus, showing off the variety of papers and capabilities. Every book included illustrations—some reproduced from the original, some using art that tied closely to the book's subject. Often the typeface used in the book was typical of a font in use at the time of the original publication. The same was true for the cover design for both the book and slipcase—it would be similar to what was in vogue at the time or inspired by the era, like seen below. Some forewords were written by a company employee, such as the head of Public Relations. In other cases, the foreword would be by an expert who could discuss the book and its legacy, even a person with a family connection to the company. Historian and literary critic Henry Louis Gates Jr., who's father had worked at the company plant in Luke, Maryland, wrote the one for Not Without Laughter, Langston Hughes' first book. For other editions, the writer might have known the author intimately. Charles Lindbergh wrote the one for his wife's book, an account of one of their international journeys.

Though the vast majority of writers selected were White males, the books chosen for reproduction weren't necessarily canonical. There are the expected American literary classics (The Red Badge of Courage, The Great Gatsby), but the team also opted for the lesser-known works of famous authors (Herman Melville, Ernest Hemingway, Langston Hughes). Occasionally they'd choose a work with a patriotic or uplifting theme (The Federalist Papers, Letters from An American Farmer; Excellence: An American Treasury), or opt for anthologies of poetry or literature, or collections of essays by one or more authors. A few are compilations featuring highlights from previous editions. The first book in the series was Washington Irving’s classic work The Legend of Sleepy Hollow. The oldest book reproduced was from 1670: A Brief Description of New-York: Formerly Called New-Netherlands, With the Places Thereunto Adjoyning, by Daniel Denton, issued in 1973. Two entries seem to be curiosities meant for perusing than for reading cover to cover. American Cookery, published in Hartford in 1796, was the first cookbook written by an American author specifically published for American kitchens; it was issued in 1963. Decorum: A Practical Treatise on Etiquette and Dress of the Best American Society, first published in 1877, gave instruction from everything on how to properly enter society and give salutations, even to the president of the United States, to advising on the proper etiquette for children at funerals. The last book produced was 50 AUTHORS: 50 CLASSICS – A MeadWestvaco Anthology. Towards the end of the series, books reportedly included interactive DVDs or music CDs.

Today, these books are easily available for purchase from used book shops and websites; a few offer the entire set (typically listed at $1,500). “Buyers obtain them not just as collectors of a unique series of books,” Scott Wallinger told me, “but also for their innate value as classic books of their respective eras.”

FHS has fifteen of the books, donated by Wayne Mullican:

- 1969 – Sailing Alone Around the World, 1895–1898 (Joshua Slocum)

- 1970 – American Notes (Charles Dickens)

- 1972 – Fables in Slang (George Ade)

- 1976 – Letters from an American Farmer (J. Hector St. John Crèvecoeur)

- 1978 – Emerson Essays (Ralph Waldo Emerson)

- 1979 – Decorum: A Practical Treatise on Etiquette & Dress of the Best American Society (ed. by John A. Ruth & Company)

- 1981 – A Young Patriot in the American Revolution (John Greenwood)

- 1985 – Almanac etc. (Twelve early American almanacs)

- 1988 – Excellence: An American Treasury (various authors)

- 1990 – Listen! The Wind (Anne Morrow Lindbergh)

- 1991 – Washington and His Generals (J. T. Headley)

- 1992 – Two Years Before the Mast (Richard Henry Dana Jr.)

- 1993 – Complete Manual for Young Sportsmen (Frank Forester)

- 1994 – You Know Me Al (Ring Lardner)

- 1997 – Not Without Laughter (Langston Hughes)