Remembering Jerry Williams (1945-2019), Forest Service Historian

Gerald W. Williams, a former national historian with the U.S. Forest Service and a Fellow of the Forest History Society, passed away on January 3, 2019. Among the many reasons for naming Jerry a FHS Fellow was his many significant contributions to the U.S. Forest Service History Reference Collection. While government reports and manuals comprised the majority of items he donated over about a seven-year period, a highlight is the 15 fat three-ring binders filled with copies of political cartoons about the Forest Service he’d spent years collecting. They have proven incredibly useful for researchers because the cartoons captured and reflected the changing popular opinion of both the agency and forest conservation dating back to Grover Cleveland’s administration in the 1890s. It also says something about Jerry as a historian. He loved the Forest Service that had employed him for his entire career, but he knew he couldn’t ignore its flaws. The expectations of the profession of history commanded his loyalty more than did the organization that signed his paycheck.

The volume of material he donated to FHS pales in comparison to what he kept at his home (more on that later.) In 2007, Jerry made arrangements to deposit his substantial personal archive at Oregon State University. The biographical notes from the finding aid summarize his career:

Gerald W. Williams worked for the U.S. Forest Service from 1979 until his retirement in 2005. From 1979 to 1993, he was a sociologist with the Umpqua and Willamette National Forests in Oregon; from 1993–1998, he served as the regional sociologist for the Pacific Northwest Regional Office in Portland; and from 1998 until his retirement in 2005 he was the national historian for the U.S. Forest Service in Washington, D.C. Williams designed and implemented a regional and national history program for the Forest Service which culminated in his appointment as national historian and his authorship of the centennial history of the Forest Service, The USDA Forest Service: The First Century, in 2000 [he updated it in 2005]. He has published more than 75 books, chapters, book reviews, and articles and conference papers exploring a variety of historical topics such as the Native American use of fire to manage environments, the Civilian Conservation Corps, and the U.S. Army’s Spruce Production Division during World War I.

Gerald W. Williams (center) received a Certificate of Appreciation from Ann Veneman, U.S. Secretary of Agriculture, and Forest Service Chief Dale Bosworth. (Gerald W. Williams Collection, Oregon State University)

Given his many contributions to the study and preservation of the Forest Service’s history, as well as that of his native Oregon and other topics relating to natural resources, I invited several people who collaborated with Jerry in different ways to join me in sharing some thoughts of him below.

—–

James Lewis (Historian, Forest History Society)

A year after coming on board at the Forest History Society in 2003, I was asked to write the companion book to the film The Greatest Good, which was being prepared for the U.S. Forest Service’s centennial in 2005. While reading in the secondary literature, I kept coming across the names of two historians: Harold Steen and Gerald Williams. I knew Steen a bit from being on a conference panel with him a few years before and from other meetings. But I hadn’t met this Gerald fellow and wouldn’t until the following year. It turns out that he was no “Gerald.” There was no pretense with him. Rather, Jerry was as easygoing and accessible a person as was his writing style. Then the national historian for the Forest Service, Jerry more than loved his job; in fact, I don’t think he ever looked at it as a “job.” He loved history, particularly but not exclusively that of the Forest Service. One only has to look at the breadth and diversity of his collection at Oregon State University to see that. And he loved collecting and ensuring the preservation of it.

But perhaps more than collecting and preserving, he loved sharing history, and he enjoyed helping you find answers to seemingly unanswerable questions, no matter how obscure. The more obscure, the more likely it is he had an answer (after all, he had more than 3,000 books in his personal collection at the time it went to OSU; he kept right on collecting after that). Jerry also had hundreds of historical photos in his personal collection. (An avid amateur photographer himself, who knows how many more he took. We can only guess based on the 15,000 slides in his collection at OSU.) When I was gathering photos for The Greatest Good book, he was extremely helpful and forthcoming with offers of assistance, quickly sending me CDs with the images from his own pictorial history of the agency to use if I wanted, and then following that trove up with even more. His book was essential for helping me identify the major issues of the last twenty years or so that I’d need to address in mine.

These requests for images were made by email or phone. It was not until Jerry arrived late one afternoon at the office that I gained a greater understanding of what made him tick. His passion for preserving Forest Service history while working in Region 6 and then at the Washington Office as the national historian was legendary, if not mythical. He’d periodically make the four-hour drive from DC to FHS with a carload of boxes filled with documents, binders, and folders to add to the U.S. Forest Service History Reference Collection housed here at the Forest History Society. When I was told by our librarian that Jerry had been “dumpster diving” again, I thought she was speaking euphemistically—that he’d simply gone around to various offices and picked up boxes. Jerry gently set me straight. With a self-effacing chuckle, he told me about literally going to the dumpster and stopping (or retrieving) the boxes on numerous occasions. What was considered unimportant to the agency he believed held value for historians—if not immediately, then at some later point. I couldn’t tell you how many times he did this before moving back to Oregon after retiring.

Whenever Jerry showed up with another delivery, we’d kid him that he’d given us so much material that we should rename the collection in his honor. Indeed, it is an important part of his legacy from his time as national historian. And, yet, there is almost nothing about him in it. Which, in many ways, fits with his character. When I learned of his passing, I went to the biographical files in that collection expecting to find a thick folder overflowing with details about his career. What I found was a single piece of paper, one that summarized Jerry’s work on behalf of and contribution to the Forest Service’s history program. In an undated letter, probably from the early 1990s, was a letter written by the director of the Public Affairs Office in Washington Office (WO) to the regional forester of the Pacific Northwest. At the time, Jerry worked for the Planning and Environmental Affairs (Strategic Planning) office in Portland. The letter informed the regional forester that Jerry was receiving a nominal cash award from the WO history unit—“a small amount” compared to all the extra time he had given for his work preserving and interpreting agency history, the director noted. “The history task is dependent on employees who do special services such as this, because there is no history function area or budget beyond the one-person staff in the WO Public Affairs Office.” The commendation read in part:

The award recognizes Jerry Williams for helping to tell our story to the public, an especially important job in recent years; special services that range from the curation of agency records and artifacts, to the authoring of numerous papers and publications, to that of public speaking at gatherings of employees and the public. In addition, Jerry is our backup for questions regarding agency history in the western United States. This vital role may not be recognized by others, but we certainly appreciate it. Overall, the dedication and productivity of Jerry Williams in support of the history program has long been recognized by the WO history unit. We are pleased to finally respond to his work with this letter of commendation.

After his retirement, Jerry happily carried on in the role of “backup” for the agency and others, always quick to respond with the answer, or an idea of where to find the answer. But he was, of course, more than just the man with the answers, more than a prolific chronicler of Forest Service history. In addition to being a scholar, he was true gentleman. And a gentle man. And it is those latter two attributes that I’ll miss most about him.

—–

Aaron Shapiro (Former National Historian, U.S. Forest Service)

Jerry Williams always had a story and they were always worth a listen. He spent much of his Forest Service career in his beloved Pacific Northwest, but in 1998 found his way to DC as the agency’s national historian. I recall conversations with him at environmental history conferences while I was researching forest history in the Great Lakes during graduate school. He was always generous with his time and shared his ideas. Jerry’s retirement in 2005 coincided with the agency’s centennial celebration and he made sure history assumed a prominent place in those events. A year later, I found myself sitting at Jerry’s desk in the Washington office, digging through materials he had left behind and, on one of my many calls to him for guidance, reminding me that much of what lay before me was collected on one of his many dumpster diving missions to preserve the documentary record. For anyone researching the agency’s history, it is fair to say that Jerry saved material that you’ve used. He reminded his colleagues of the value one could find in the agency’s past and how it could inform current decision-making. He wrote papers galore. And he never tired in his belief in the power of the story. I remember one early conversation when Jerry reminded me that he was actually a sociologist, one of the “ologists” that joined the agency in the years after NEPA. But despite whatever it said on that long-ago degree, Jerry Williams was undoubtedly a historian who knew the importance of a good story. He will be missed, but his words and work remain with us.

—–

Gerald Williams posing with the Gifford Pinchot National Forest marker. (Source: MSS WilliamsGElectronic; Date: June 24, 2008)

Steven Anderson (President, Forest History Society)

Jerry was a Forest History Hero; a person who strongly believes in the value of history to help us make the best decisions now and in the future. He was a regular visitor to the FHS headquarters, constantly bringing additions to be added to the U.S. Forest Service Headquarters History Reference Collection housed at FHS. He told us he was dumpster diving for some of the material and we believed him. Whenever we were stumped on a USFS inquiry we knew that Jerry was ready to lend a hand and his knowledge to the challenge. He was a prolific writer of agency history and many have benefitted from his insights. And he never hesitated to express his appreciation for FHS’s efforts to save Forest Service history when others would not.

For his career-length efforts, in 2014 the Forest History Society recognized Jerry with its Fellow Award, its highest honorary award bestowed on people for either (1) many years of outstanding sustained contributions to research, writing, or teaching relating to forest history, and (2) for many years of outstanding sustained leadership in one or more core programs or major activities of the Forest History Society. Jerry Williams was one of the few honorees who qualified in both categories.

We will miss his humor, wit, congenial manner, and his approach to collaborative efforts.

—–

Dave Steinke (U.S. Forest Service–retired; Co-Producer/Co-Director of The Greatest Good)

I really got to know Jerry Williams in September 2001, when a group of filmmakers and historians were locked down at the Pinchot estate Grey Towers in Milford, Pennsylvania. We were about to have our first planning meeting about a Forest Service documentary, The Greatest Good, when New York and Washington were attacked, grounding all flights for several days. It was the weirdest of times and yet some of the most memorable times ever. That time together sparked long philosophical discussions about world politics as well as a deep dive into Forest Service history.

From that day forward, Jerry was my go-to history guy. If I needed a quote or a book reference or to understand the story of the Yale lock or who the first female district ranger was, Jerry had the answer.

He had one of the most amazing libraries in his basement—mostly natural resources and western history—with a huge amount of Forest Service ephemera. He knew where every book was and an appropriate quote for every occasion in each.

Jerry was invaluable to me as a public affairs officer and a filmmaker for the U.S. Forest Service for decades. His white papers, books, references, reviews and contributions to hundreds of documents in the public domain will remain forever as a tribute to dedicated and knowledgeable public servants.

He will be missed.

—–

Bibi Gaston (author, Gifford Pinchot and the Old Timers)

Jerry Williams was a gentleman, the kind of gentle soul Gifford Pinchot would have greatly appreciated for his accuracy, reliability, and humility. He had a dog. He lived alone. He spoke kindly and listened carefully. He seemed to want to share with me things and share his love of history. His gentle demeanor was what I remember.

We spoke many times over the phone about the early foresters trained under the first Forest Service chief. We first met when he attended a talk I gave at the Wasco County Historical Society in the Dalles, Oregon. I did not know who he was but he came up to me after the talk, introduced himself, and handed me several photos of Gifford Pinchot. Many years later we met for lunch at McMenamins-Edgefield in Troutdale, just outside Portland. That time, Jerry arrived with a cardboard box that contained a small glass display case filled with political buttons, ribbons, and political memorabilia, a treasure from his lifetime of collecting the artifacts of the Forest Service story. I wasn’t sure whether he wanted me to know that my great grand uncle Gifford had aspirations for higher office, including the presidency, or whether he just wanted me to see the pins. He didn’t say. He just wore a great big grin on his face and that was enough. Nonetheless, at lunch he gave me a thumb drive with hundreds of political cartoons he had collected. The drive offered proof of Jerry’s dedication and commitment to preserving the ideals Pinchot instilled in the early men and women of the U.S. Forest Service: absolute accuracy, reliability, and humility—qualities essential to the health and well-being of the nation.

—–

Steve Dunsky (U.S. Forest Service; Co-Producer/Co-Director of The Greatest Good)

Like many of my colleagues, Jerry Williams knew that he had the best job in the Forest Service.

And, indeed, the position of national historian was a marvelous fit for his skills and his passions. He loved to search the archives for context on the origins of a policy issue. He delighted in the material culture and traditions of the agency.

His white papers were carefully researched and clearly written. Even in retirement, Jerry would respond quickly to any query. I will miss his expertise and, more importantly, his friendship. Jerry was not a historian by training or academic degree, but he was a true professional and a wonderful colleague who taught me a great deal about our Forest Service.

—–

Char Miller (Historian, Pomona College)

Jerry Williams, who rose through the ranks of the U.S. Forest Service to become its national historian, a post he held between 1999 and 2005, had a keen appreciation for the past. To wit: He intentionally set the date of his retirement for July 1, 2005, he told me over a companionable lunch several months earlier, because that marked the agency’s 100th birthday.

That Jerry paid close attention to such moments may have had something to do with his first love (sociology), and his second (history). All his degrees were in sociology, and he had a lifelong fascination with the human dimension of the institutions and organizations that we construct. But he also reveled in the historian’s pursuit of sources and context. His writings—talks, articles, and books—reveal Jerry’s deep commitment to reading absolutely everything he could get his hands on that would help him better understand, for example, the policies that the Forest Service implemented in  the Pacific Northwest. Policies whose social consequences, the sociologist in him knew, were differently felt in areas rural and urban. But the historian also wanted to know what these decisions’ ramifications might be on the land itself, and that would lead him to burrow into archives, filing cabinets, and storage closets. He mined these repositories for all they contained, and much of what he discovered there gave substance to his two post-retirement books, The Forest Service: Fighting for Public Lands (2006) and The U.S. Forest Service in the Pacific Northwest: A History (2009).

the Pacific Northwest. Policies whose social consequences, the sociologist in him knew, were differently felt in areas rural and urban. But the historian also wanted to know what these decisions’ ramifications might be on the land itself, and that would lead him to burrow into archives, filing cabinets, and storage closets. He mined these repositories for all they contained, and much of what he discovered there gave substance to his two post-retirement books, The Forest Service: Fighting for Public Lands (2006) and The U.S. Forest Service in the Pacific Northwest: A History (2009).

It’s also true that much of what he unearthed, he kept; Jerry was a legendary packrat. Whatever that penchant may have done to his home, we will be the lucky recipients of his collector’s instinct. He deposited 93 cubic feet of documents, oral histories, maps, photographs (25,000 of them!), cartoons, videos and sound recordings, among other cultural materials, in the Special Collections and Archives Research Center at Oregon State University Library. Although his papers are currently closed for processing, one piece of family treasure I cannot wait to see are a series of photographic slides Jerry’s father took in September 1956 of a free-flowing Celilo Falls on the Columbia River, just months before the Dalles Dam inundated this sacred site.

A gifted photographer himself, Jerry had a kind of snapshot memory. Sometime in the mid-1990s, while writing a biography of Gifford Pinchot, I mentioned to him that I was hunting for evidence that would document a crucial discussion that reportedly had occurred in 1897 between Pinchot and John Muir in Seattle’s Rainier Grand Hotel. I had worked my way through both men’s journals and correspondence, through local newspapers and countless books, and suspected the moment was not quite as explosive as many had claimed. What I could not find, I sighed, was contemporary confirmation one way or the other. It took him five years or so, but in 2001, after I finished talking about Pinchot at Powell’s Books in Portland, Jerry handed me a 1901 letter Muir had written that gave additional substance to the story. Whenever I teach this particular episode in my U.S. environmental history class, I do so as a form of historical detection, laying out who knew what, when, and how. My students crack up when they read the final document, that Muir letter. They recognize that Jerry had schooled me, the perfect teaching moment.

—–

Lawrence A. Landis (Director, Special Collections and Archives Research Center, Oregon State University Libraries and Press)

The Oregon State University Archives first crossed paths with Jerry Williams in early 2007, when OSU’s library director and I met with Jerry and the Portland dealer who was marketing his massive collection of historic photographs and maps, personal papers, books, and artifacts. We soon made the decision to purchase the collection, as it was clear from that initial visit that it could serve as a cornerstone for the Archives’ collecting effort to document natural resources in the Pacific Northwest. The collection was transported to OSU in October 2007 in two very full vans, seen in photos on the OSU Flickr site.

The Archives quickly created a box level finding aid in order to provide some immediate access to the collection. At the same time, selected images from the albums Jerry had assembled (mostly by watershed basin) were digitized and made available through Flicker Commons. Within weeks of posting the images, the Archives began receiving inquiries about the collection and use of the images posted online. Ultimately these images were made a collection in Oregon Digital, a platform co-developed and managed by the OSU and University of Oregon Libraries.

The Williams Collection images certainly raised the visibility of all of the Archives forestry and other natural resources related collections. Although the collection was purchased, Jerry (ever the collector) continued to add to it until recently, through donations of materials he would find at book and paper shows, antique shops and other venues. He was also very generous with his time in answering our questions about the collection and helping us to promote it, especially to scholars.

Because of the extensive nature of the collection as a whole, we made the decision to describe discrete components of the collection, rather than create one very large and potentially difficult-to-navigate finding aid. This has been a multi-year effort that is nearing completion, and has resulted more than two dozen finding aids, which are available on the Center’s website as well as Archives West. Individual volumes from Jerry’s book collection were added to the Libraries’ general and rare book collections, as well as the library collection at OSU’s Cascades Campus in Bend, Oregon. Numerous volumes with no copyright restrictions were digitized and made available through the OSU Libraries’ scholarly repository, ScholarsArchive@OSU.

Since 2007, the Gerald W. Williams Collection has been used by a multitude of researchers, ranging from OSU undergraduates to guest scholars who have participated in our Resident Scholar Program. Images from the collections have been used in numerous publications and exhibits, as well as multiple episodes of Oregon Public Broadcasting’s award-winning Oregon Experience television series. The breadth and depth of these materials collected, assembled and created by Jerry Williams will continue to be a treasure trove for scholars and other researchers for years to come.

—–

Mary Braun (Former acquisition editor, Oregon State University Press)

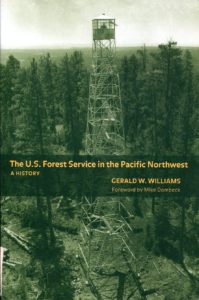

In 2009, OSU Press was pleased to publish Jerry Williams’s book The U.S. Forest Service in the Pacific Northwest: A History, with a foreword by Mike Dombeck. Thoroughly researched, and grounded in his career experiences in the U.S. Forest Service, the book chronicles the agency’s evolving management of almost 25 million acres of national forests and grasslands for more than a century in the region the author called home. The text is richly illustrated, many of the images from his own collection, and accompanied by appendices that provide detailed data about the extensive forests of the Pacific Northwest. Jerry Williams was the ideal author to write the book.

—–

Stephen R. Mark (Historian, National Park Service, Crater Lake National Park)

I met Jerry very early in my career, within weeks of starting my tenure as a National Park Service historian at Crater Lake. Jerry quickly shared much of what he had written on the Forest Service to that time (1988) and soon pulled me into a developing project of his—about the origins and early defense of the Cascade Range Forest Reserve, the “mother” of national forests in Oregon. What served as an antecedent began when Jerry located some illuminating source material from a key advocate of the CRFR. “Judge John B. Waldo: Letters and Journals from the High Cascades of Oregon, 1877–1907” went through several iterations between 1988 and 1992, also serving as a foundation for his article that appeared in the anthology The Origins of the National Forests published by the Forest History Society in 1992.

Jerry relocated from Eugene (where he split his time working on the Willamette and Umpqua national forests) to the regional office of the Forest Service in Portland by the mid-1990s. He suffered through an extended period of illness around that time, but the silver lining was that Jerry’s efforts made the CRFR project come to fruition in September 1995, as an indexed sourcebook of more than 1,000 pages. Only 25 copies of this volume exist, but it is emblematic of what he often produced as a historian: an insightful and succinct analysis based on sources that were usually new to the reader, especially if he included items from his collection.

Although Jerry visited a few times from DC during his tenure as the Forest Service’s National Historian, I met with him far more often after his retirement on July 1, 2005. The most memorable occasion took place in the spring of 2014, when I organized a session on how to reach audiences with park and forest history at a meeting of the National Council on Public History in Monterey, California. Jerry’s illustrated talk on Forest Service history, one that he gave many times at all levels of the agency that he’d chosen for a career, was a huge hit. It marked the final time I saw him in person, but Jerry’s legacy is plainly evident at the Forest History Society and through the Oregon State University Archives in Corvallis.