Remembering Harold Bell, Creator of Woodsy Owl

This past weekend the New York Times reported the passing of Harold Bell on December 4 at age 90. Mr. Bell was one of the creators of Woodsy Owl, the Forest Service’s anti-pollution mascot. He was working with agency employees Glenn Kovar, Betty Conrad Hite, and Charles Williams (who gave Woodsy his slogan “Give a Hoot — Don’t Pollute!”) on the television show “Lassie.” Mr. Bell was there in his capacity as a marketing agent, the others as technical advisers (since Lassie “belonged” to Forest Ranger Cory Stuart), when the Forest Service asked them to develop a new mascot to fight pollution. A self-taught cartoonist, Mr. Bell did the first drawings of Woodsy.

It was the late 1960s, when the environmental movement and concern for the earth were taking off. Newspaper editors were technically breaking a law by using Smokey Bear in media campaigns against pollution. (Federal law restricts Smokey to discussing firefighting issues. Woodsy has greater latitude. In addition to advising against littering, he has for several years been encouraging folks to “Lend a hand, care for the land” by planting trees and other activities.) The Forest Service developed Woodsy in part to get involved in the burgeoning environmental movement. Though created in time for the first Earth Day in 1970, he wasn’t formally introduced until September 15, 1971. Congress passed legislation protecting Woodsy’s image and establishing his licensing requirements in 1974. Funds from licensing agreements went to promoting education about conservation and fighting pollution. As we approach the fortieth birthday of the friendly owl, and given Woodsy’s message and the Forest Service’s emphasis on land restoration and conservation these days, it seems like the perfect time for Woodsy to make a return to the spotlight.

Because Woodsy was aimed at preschool and grade-school children, Mr. Bell and his creative team quickly settled on a woodland creature found in the wilderness as well as urban forests — the owl. Their owl would not be a wise old owl who might seem to be lecturing kids about pollution, but rather a young one with a kind face who, when in costume, could look children in the eye, which made it easier for them to relate to Woodsy. Within a few years of his introduction, a national survey found that Woodsy and his message were recognized by 90 percent of U.S. households with children and by 70 percent of the general population. Like his older “cousin” Smokey, Woodsy had his own song, appeared in television ads and children’s programs, and generated tons of fan mail from children around the country. (As discussed on this blog before, however, neither icon is in the Madison Avenue Advertising Walk of Fame, which is especially criminal in the case of Smokey.)

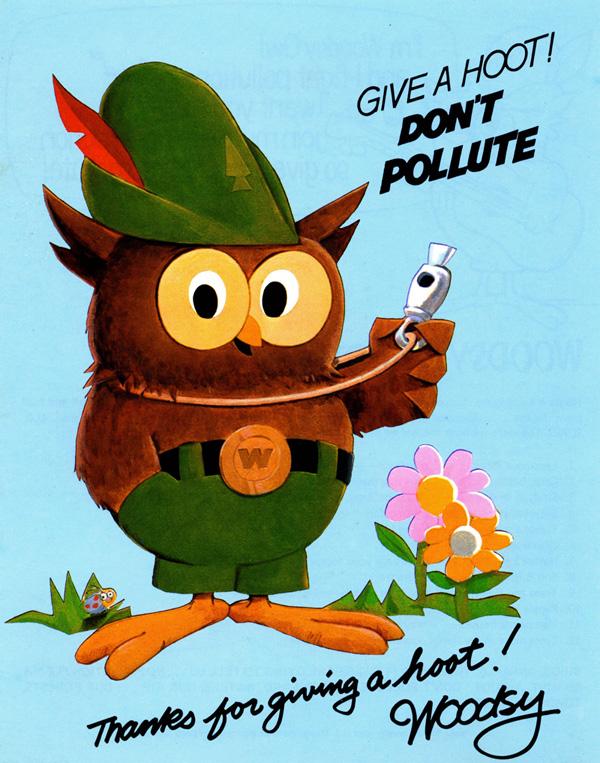

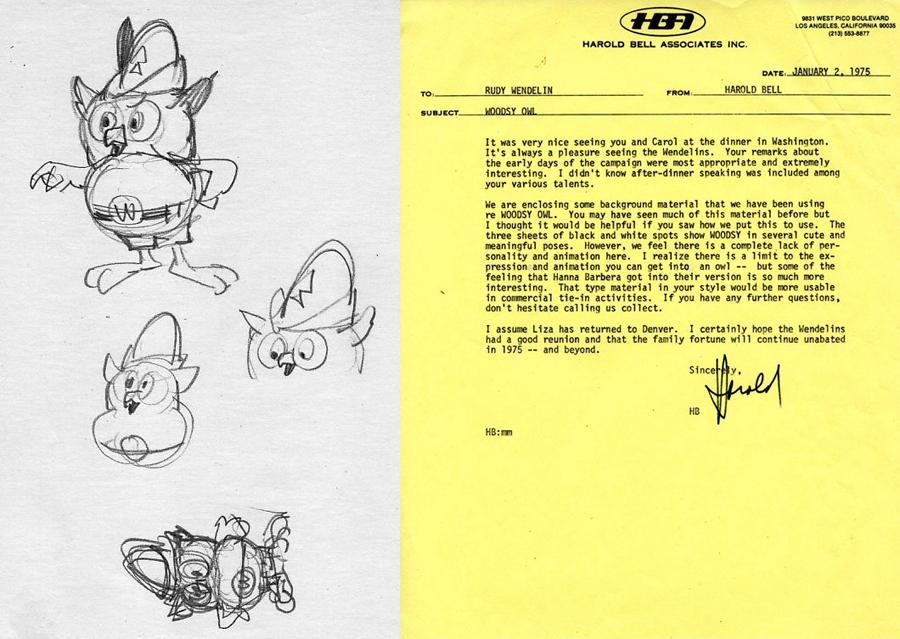

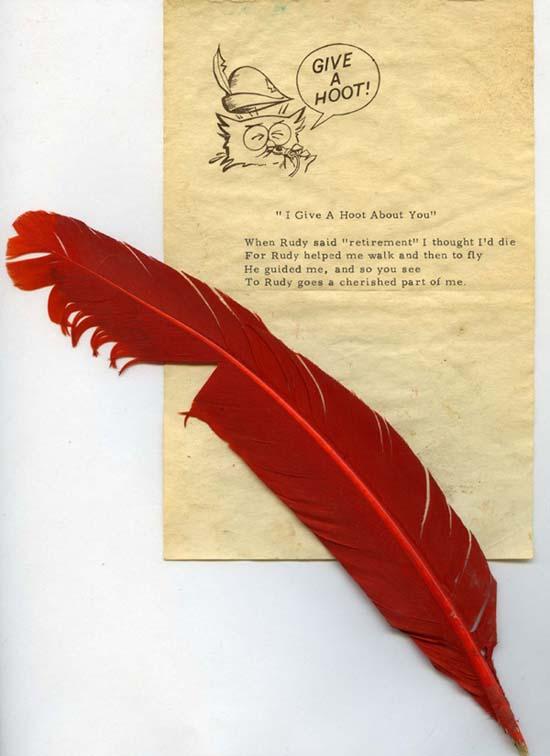

Woodsy and Smokey had another thing in common — Rudy Wendelin served as the lead artist for both characters. Complementing the materials in the U.S. Forest Service History Collection on Woodsy, which include education kits and a memo from 1988 debating whether to transfer or terminate the Woodsy program, the Wendelin collection has lots of cool Woodsy material. Rudy was brought in fairly early on in the development process to help bring Woodsy to life. Below are just three of the items: original artwork of Woodsy by Rudy, a January 1975 letter from Harold Bell to Rudy requesting Rudy’s help in giving Woodsy more “personality” in his face, and a thank-you note to Rudy with a feather from Woodsy.

Woodsy Owl, from the Rudolph Wendelin Papers.

The letter from Harold Bell to Rudy Wendelin discussing Rudy doing some work on Woodsy, along with some of Rudy’s earliest sketches (Rudolph Wendelin Papers).

When Rudy retired, Woodsy made the ultimate sacrifice for the man who gave him “personality.” (Rudolph Wendelin Papers).

Told you it was cool stuff!