National Pancake Day and Lumberjack Breakfasts

Today is National Pancake Day at the International House of Pancakes. You can get a free short stack of pancakes, though IHOP customers are encouraged to make a donation that will go to a local charity. (This date should not be confused with International Pancake Day, which is when a foot race between the women of Liberal, Kansas, and Olney, England, takes place that starts and ends with participants flipping a pancake in their pans. Seriously.)

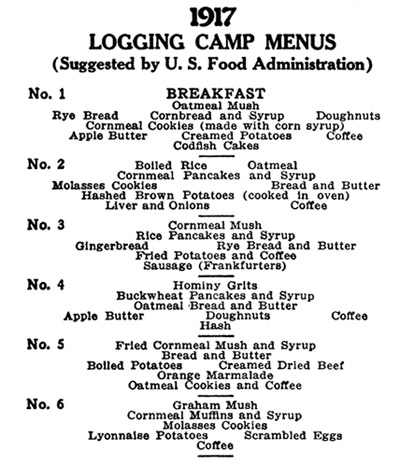

IHOP’s short stack wouldn’t begin to fill a lumberjack of yore, though; it might only whet their appetite. What do I mean? According to author Joni Sensel in Timber/West (Nov. 2000), “Camp records indicate that on average, a logger in the Northwest around the turn of the [20th] century might start the day before dawn with flapjacks, eggs, bacon, fired pork, hash, spuds, oatmeal, prunes, fruit, doughnuts, biscuits, or all of the above.” And “all of the above” better be above average or the cook would hear about it: “Loggers never put up long with this sort of thing,” Joseph R. Conlin tells us in his excellent article, “Old Boy, Did You Get Enough of Pie?” “If they did not walk off, they put the unsuccessful cook on notice that it was time for him to leave by nailing some of his hotcakes to his door.” So important was feeding the men quality food that the cook was often the highest-paid employee in a logging camp. He was “Godamighty,” wrote Stewart Holbrook in Holy Old Mackinaw, his classic history of the American lumberman in the 19th century.

Loggers consumed on average about 9,000 calories a day—3 to 4 times what most of us require (by comparison, endurance athletes such as distance runners and cyclists might take in up to 8,000 calories per day). And the lumberjacks needed every calorie they could get. Given the 12-14 hour days, exhausting nature of the work, and brutal weather conditions in which they worked during the winter months, breakfast was, to coin a phrase, the most important meal of the day.

Each day a man typically consumed “a half a loaf of bread, a pound of potatoes, a pound of other vegetables and fruit, plus cold cuts, salads, baked beans, stew, or soup,” plus dessert, Sensel cataloged. Meals were consumed in 8 minutes, with speed aided by the “no talking” rule and the need to take in all a man could—slow eaters would later be hungry. Keeping a camp of a hundred men supplied required bringing in vast quantities of food. Syrup for pancakes, for example, was delivered in barrels. The fare varied by season and region, and by era. Before refrigeration, fresh meat was rarely seen in the summer or was cured or dried, like ham or bacon. A more permanent camp might raise pigs for fresh meat. In the 19th century, fruits and vegetables were largely in dried form; by the end of that century, they were shipped in tins and cans; and then by the Great Depression, the camps regularly received fresh fruits and vegetables.

Holbrook says that for 19th-century loggers in New England and then the Great Lakes, “The fare was pretty much salt pork, beans, bread and molasses, and tea, black tea strong enough to float an ax on.” Contrast that with Sensel’s and Conlin’s descriptions of food and how much more variety there was. By the time the “lumberman’s frontier” had moved to the Pacific Northwest, loggers were eating better than most Americans. This was due in part because the large, integrated logging companies there “had the resources necessary to maintain their own ranches and farms,” according to Conlin. Coffee had replaced tea as the preferred caffeine source of choice, sometimes served in a soup bowl. Notes Sensel, “One logger might account for almost a pound of ground coffee a week.” I doubt that they were ordering their coffee with a twist of lemon.

In honor of National Pancake Day, we’d like to share some pancake-themed photos from our archive. The Paul Bunyan images are from the Mead Sales Company Paul Bunyan Campaign Collection and the William B. Laughead Papers. And with that, we’re off to get our free pancakes!

Pancakes are part of an Idaho logging camp breakfast (FHS5106).

The legendary lumberjack Paul Searls puts away a logger’s-size stack of hotcakes (FHS5083).

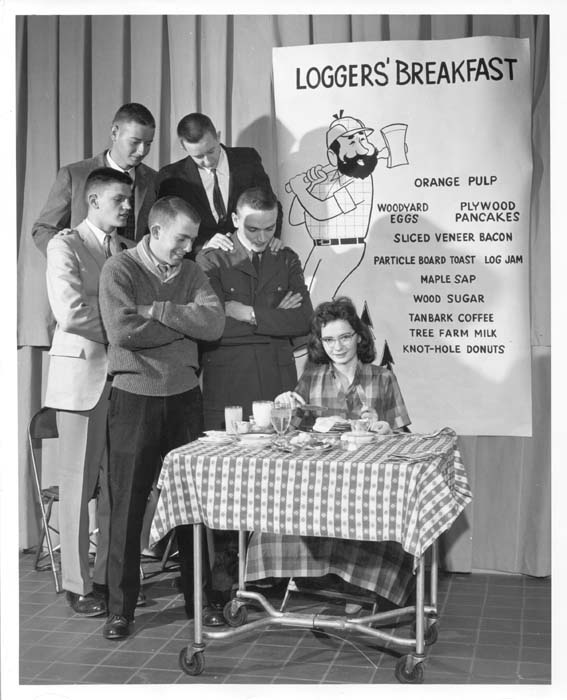

A “Logger’s Breakfast” for the national 4-H Forestry winners at the 1960 National 4-H Club Congress (FHS1875).

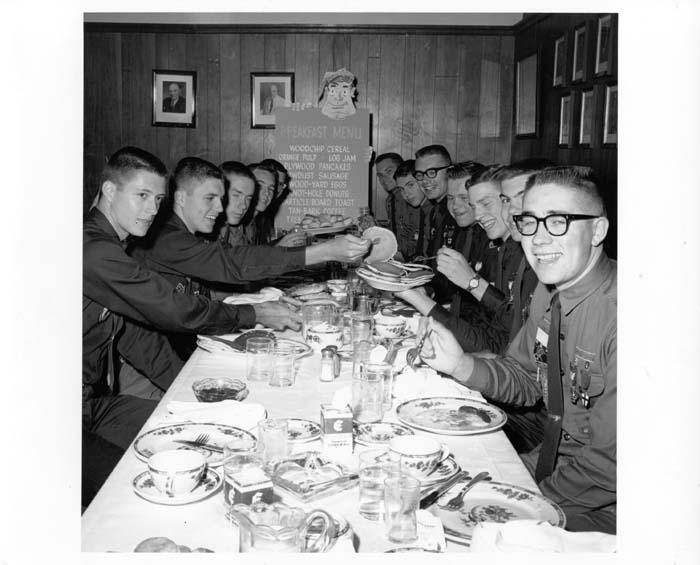

A “Logger’s Breakfast” hosted by AFPI for Boy Scouts who won national conservation awards, 1962 (FHS567).

Postcard of Big Joe, Paul Bunyan’s pancake cook (Laughead Collection).