“How Great the Gain!”: Women and the Forest Service

This post, coauthored by James G. Lewis of the Forest History Society and Rachel D. Kline of the U.S. Forest Service, was originally published in a special issue of the journal Western Forester on "Women in Forestry" in August 2021. The journal is published by the Society of American Foresters' Oregon, Washington State, and Alaska Societies Northwest Office. Many thanks to editor Andrea Watts for permission to republish it.

You can download the article as a PDF HERE, and access the entire issue online HERE.

When a group of female employees met with U.S. Forest Service leaders, including the chief, in March 1924 to discuss how the agency could “make working conditions pleasant” for women, a Miss Peyton, who had worked there for 20 years, spoke first:

The first summer after I came to the Service, a group of freshly-graduated students arrived from one of the forest schools, painfully young, immature looking, and inexperienced… Then suddenly something else caught and held my attention. The Service didn’t see mere boys. It saw potentialities. It was not looking at the present. It visioned the future.

She then asked that women be afforded the same treatment as the new hires, to be given greater responsibilities and the opportunity to advance. In talking about the other 100 women employees at the national headquarters, she continued:

Their history might in fact be written to a large extent in four words: No responsibilities, no experience. And the result? … What has happened to them might easily be indicated in three fateful words: Unused faculties atrophy. Think of it — … [they’re] retrograding instead of developing! … Now, reverse the picture, and thereby get a glimpse of these same women as an army of well-developed trained workers. How great the gain!

On behalf of the other women throughout the agency, she asked that there be “ways in which women employees may be given additional responsibilities so that they may increase their value to the Service and at the same time afford a basis for advancement in rank, salary, and self-respect.”

VITAL YET OVERLOOKED

At this time, women were already showing their worth as clerks, typists, librarians, education specialists, and researchers—jobs considered gender appropriate at the time.

Working in the Washington Office, district offices, and libraries, women helped pioneer the agency’s information infrastructure—creating filing systems and bibliographies, disseminating information to the public and staff, as well as providing cohesion in the office as rangers and other male staff came and went. Helen Stockbridge served as director of the Forest Service Library from 1904 to 1933. Between 1904 and 1910, she increased the library’s holdings four and one-half times to 13,000 items, acquiring and indexing diverse literature, establishing libraries in every forest supervisor’s office, and distributing knowledge. Stockbridge’s and others’ bibliographies, writings, and editing influenced the distribution of information on forestry, thus transmitting a female perspective into decisions made by foresters in the field.

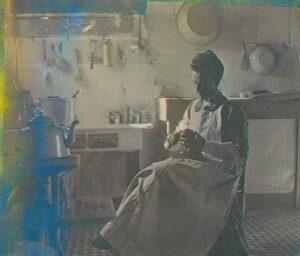

Charles and Julia Shinn bought a rundown cabin they transformed into the legendary first office of the Sierra National Forest. Julia later wrote that the two livable rooms, out of necessity, became the “living room-bedroom-office and a kitchen-dining room-laundry.” (From "Julia Shinn – Our Sierra Mother" by Marie Mogge, https://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet /FSE_DOCUMENTS/fseprd499738.pdf

At some remote ranger stations, rangers’ wives served as clerks, but for no pay and while also trying to run a household. The Forest Service considered wives a convenient and necessary free source of labor on understaffed ranger districts. In addition to clerical work, they helped with field duties and ran the ranger station while their husbands were away. They also fought fires and served as nurses and camp cooks on the fire lines, and then helped prepare fire reports by estimating timber and forage losses, and even analyzed the causes of the fires.

Despite rules against nepotism, the need for good field leaders was such that some wives were quietly put on the payroll in order to save their husbands’ jobs. Charles Shinn’s superiors agreed to keep him on as long as his wife Julia worked for him. They worked side by side for four years, until he retired in 1911. Julia continued for another 12, serving as a de facto district ranger. She was so knowledgeable of local conditions that her husband’s replacement had to notify all forest personnel that they were to come to him—not Julia—to discuss their issues. He knew he could not establish himself as supervisor as long as the men looked to her for leadership and advice.

Another area in which women greatly contributed to conservation was education. In the 1920s the Forest Service’s Eastern Region created a program within the Division of Information and Education called Women’s Forestry to work closely with school children and local women’s clubs. Women’s Forestry expanded the agency’s publicity messaging and assisted women’s organizations in planning forestry programs on fire prevention, tree planting, and the importance of forests as a treasured resource.

The program proved so successful that the national headquarters created its own Director of Women’s Forestry position in 1942. That same year, in an article for American Forests magazine, national director Margaret March-Mount wrote, “No longer is forestry wholly ‘a man’s profession.’ The wonder-world of the forest is now a woman’s world also.”

Margaret March-Mount (far left) visited women’s clubs and children all over the country. One way to introduce and involve women’s groups in conservation was leading them on field trips called Conservation Caravans, like this one for the Minnesota Federation of Women's Clubs in June 1940. (U.S. Forest Service, Eastern Region photograph, Forest History Society Collection, R9_419148)

She outlined the program’s goal: to make women into “forest builders” who would protect the forests as their homes. She claimed that women could build careers at home as foresters, working on the “human side of forestry.” March-Mount’s program revealed the contrast in men’s and women’s approach to forest conservation—while Forest Service men predominately viewed timber as a crop to be harvested, women desired to build up forests to enhance American life.

GETTING A RUNG ON THE CAREER LADDER

In the field, the only position limitedly offered to women was that of fire lookout. During the 1910s and 1920s, and again in the 1940s, women proved so successful as lookouts that some male Forest Service officials claimed women were better suited to being lookouts than men—having greater patience and endurance than men, as well as being more vigilant at the task at hand: women weren’t tempted to go fishing or hunting. The male anxiety of female lookouts perched high atop lonely mountains, however, deterred many male officials from hiring women for the position.

Until 1978, women did not hold field positions such as forest ranger, or any field supervisory positions from district ranger on up. An agency employment leaflet from around 1950 explained why: “The fieldwork of the Forest Service is strictly a man’s job because of the physical requirements, the arduous nature of the work, and the work environment.” It was a Catch-22: the position of forest ranger was “a man’s job” because they had only hired men to do it. The only way to find out whether a woman could do the job was to hire one, but no one wanted to risk their career to do so. Working in the field or on the fire line were the two fastest ways to climb the company ladder, and women weren’t allowed even on the first rung, except in times of crisis. Even after women formally served on fire crews and cruising timber—to name just two traditional male jobs that women effectively handled—during World War II, the agency would not permanently change its policy about allowing women to apply for field positions for another three decades.

One way that women have participated in the agency’s information infrastructure is by gathering data. Here, a ranger’s clerk taking weather readings to determine fire dangers on the Chippewa National Forest, Minnesota, August 1968. Another difference between how men and women employees were treated is noticeable in the uniforms. Women weren’t issued official uniforms until 1964, and weren’t allowed to wear pants until 1972—the same year they were issued their own work uniform. (U.S. Forest Service, Eastern Region photograph, Forest History Society Collection, R9_518845)

Nearly 30 years after that 1950s leaflet was published, Geraldine Bergen Larson challenged the definition of what was women’s work. “Geri” was in her early 30s when she finished top of her class in forestry school in 1962. She began as a research forester because women couldn’t become field foresters. Bored with the job, she earned a master’s in botany and then became a Public Information Officer in 1967, working with garden clubs and other groups with conservation interests in California, like Margaret March-Mount before her.

After further building her credentials as the regional environmental coordinator, in 1978 she applied for a deputy forest supervisor position. The forest supervisor and regional forester supported her application. She was offered the job, but only after assuring them that her husband accepted their having a commuter marriage. With that settled, she became a line officer, the first female one in the agency’s history. She was also one of the first line officers not to have served as a forester or engineer.

The spate of environmental laws in the 1970s created an immediate and substantial demand for employees with expertise in non-forestry fields, such as wildlife biology, recreation, and landscape architecture. Women working in natural resources who entered the Forest Service during this period brought with them a different perspective on the relationship between humanity and the environment, as they had for decades. A survey conducted in 1990 found that women “exhibit greater general environmental concern than men,” and in particular were more in favor of reducing timber harvest levels on national forests and designating additional wilderness areas.

Subsequent studies have shown little or no difference in attitudes concerning general environmental issues, but have shown that women exhibited “significantly more concern than men about local or community-based environmental problems.” These values more closely reflect those of the general public, helping the agency better align itself with the constituency it serves. It also brings things full circle. Since the agency’s inception, women have participated in conservation by building up forests and communities through means other than serving as professional foresters. The women’s clubs of a century ago depended on male foresters to carry out their reforestation programs. Beginning with Larson, who entered the all-men’s club by way of botany and policy work, women have held positions at every level in the Forest Service and are making decisions about forests—making the forest a woman’s world, too, as March-Mount had visioned.

But the door to the all-men’s club began opening for Larson and others only after the expansion of civil rights to include the banning of sexual and racial discrimination in the 1960s. This huge cultural change for the Forest Service occurred slowly, and largely because legal action forced open the door. In 1973, when a hiring manager made clear he preferred to wait for a male applicant rather than hire Gene Bernardi for a research sociologist position in California, her complaint garnered compensation but not the job. Fed up, she and other women filed a class-action lawsuit in the California region over sexual discrimination. The issue dragged on for years as the agency failed time and again to comply. In the end, the Forest Service was compelled to hire more women. As women moved into traditional male roles like smokejumper, forest ranger, and law enforcement, they faced backlash and discrimination from many, but found encouragement from others, like Larson did. But the issue of underrepresentation and discrimination has persisted. While the agency has worked for half a century to ensure that the composition of its workforce increasingly resembles that of the American public it serves, in all likelihood, the agency’s hiring and promotion practices will remain under scrutiny until parity is achieved and discrimination is eliminated.

Since the agency’s founding, women have been contributing to the Forest Service’s mission and conservation as a whole. For much of its history, the agency continually kept women out of the traditionally male professional fields, simply by declaring certain jobs as inappropriate for women, even though women had proven themselves capable when given the chance. Faced with legal action in the 1970s regarding how it managed its personnel, the Forest Service had no choice but to change its ways. It took female employees forming their own “club”—more precisely, a legal class—to force the agency to redefine what was considered gender-appropriate work. In many ways, today’s situation echoes Miss Peyton’s plea: Imagine what can be gained by looking at employees for their potentialities, and not their sex.

James G. Lewis is the historian for the Forest History Society and the author of The Forest Service and The Greatest Good: A Centennial History. Rachel D. Kline is a Supervisory Historian for the U.S. Forest Service. She earned her PhD in History at the University of New Hampshire.