How Forest History Can Be Like A Beethoven Symphony

This post is adapted from the Editor’s Note in the Spring/Fall 2020 issue of Forest History Today.

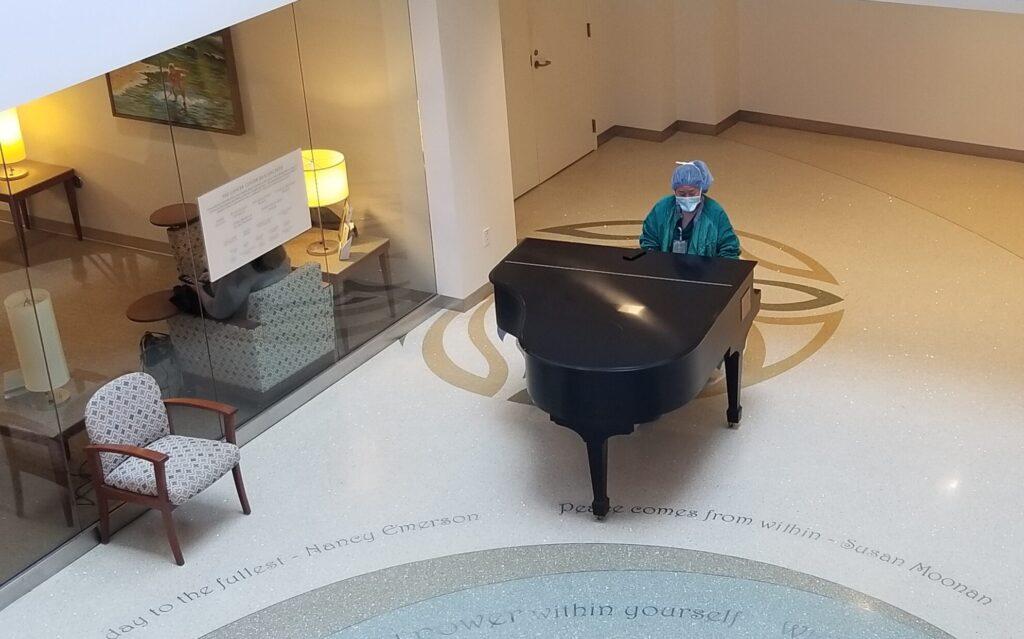

As I sit here in a medical facility in December, waiting to be called, surrounded by people wearing masks because of the global pandemic, I hear the welcome sound of someone playing a piano. A staffer, dressed head to toe in personal protection equipment, is taking a break from their critical work to play a mix of holiday tunes and standards both popular and classical in an effort to lift the spirits of patients, caregivers, and workers. Embedded in the floor, inspirational quotes from patients swirl around the piano. The music rises up through the five-story atrium and out into the waiting areas on each floor, swirling around us. Every note I hear carries with it the sound of hope and a reminder of our resilient nature in a very dark time in our history.

On any given day, it seems the news about the environment and forests in particular is also overwhelmingly dark. Wildfires are so large that a new term—gigafire—has been coined to describe them. New temperature records are being set both locally and globally. Drought, disease, invasives: these and other environmental factors are devastating forests around the world. If the news were a music genre, it would be a dirge.

For decades, the interpretation of forest history has been declensionist; that is, telling a tale of degradation and despair, giving a bleak picture of the past, and often offering little hope for the future. But not all forest history is a tragedy, not every song a lament. There have been “composers” of history who instead write of progress. Of course, what is necessary for measuring progress is that one must have a dark period from which to emerge. Think of Beethoven’s Sixth, the Pastoral Symphony. The fourth movement, “The Storm,” evokes thunder and rain before bringing the audience to the last movement, what the composer subtitled “Cheerful and thankful feelings after the storm.” To a historian, words are musical notes. When strung together, sentences combine to create movements; an article documenting progress is a symphony of accomplishment and promise. There are stories of recovery and hope to be found in forest history, just as there are musical works like the Pastoral Symphony that take the listener through a dark passage before giving way to music that raises spirits, much as the piano notes heard in that atrium did.

Though it’s important to analyze problems, at the same time it’s vital to discuss what’s working and what’s improving—and also what is not. Articles in the forthcoming issue of Forest History Today—Stephen Pyne’s on a turning point in global wildfire history, Joe Hamrick’s piece about using century-old working plans for pine management in Texas, and Ellen Sharp and Will Wright’s article about two generations of rangers protecting Mexico’s monarch butterfly biosphere reserve—can educate us about what is and isn’t working, even if the ending has yet to be written. In talking about the Miramichi Fire of 1825, which burned in two countries but is remembered differently in each, Alan MacEachern demonstrates the power of historical memory. Char Miller, in writing about the forester W. W. Ashe, and Hugh Canham, in his story of the Otsego Forest Products Cooperative, tell of efforts that succeeded and those that did not, respectively. What Kenneth Jolly, Gordon Small, and Adam Sowards remind us of in their articles about men and women anonymously toiling for public agencies in the name of conservation is the value of retaining optimism in the face of long odds.

Taken as a whole, these stories remind us of the transformative powers of hope and optimism—and of our resilient nature and that the resiliency of nature, too—so that while we are in the midst of the storm and in the middle of the darkest of passages, we know that some day we may again have cheerful and thankful feelings after it has passed.

Hope can be found in unexpected places. Sometimes it’s a medical worker playing piano in the middle of a medical clinic; sometimes it’s in a forest history article.