When Forester Ray Conarro Moved to Mississippi, Good Things Happened.

Imagine how Ray Conarro (1895–1977) felt when his superiors made him the inaugural supervisor of the Homochitto Purchase Unit in Mississippi—for which no land had yet been purchased. His charge not only was to secure a requisite land base for that unit but for five others in the Magnolia State. In short, his mission was to create the National Forests of Mississippi. Conarro leapt at the opportunity.

He had had a formative experience on another start-up forest, the Allegheny in northwestern Pennsylvania. As a land examiner, he assessed large tracts of cutover forests in the Allegheny Plateau. It helped that he knew the terrain, having grown up in Warren, which was the new forest’s headquarters. It helped, too, that he was smart, detail-oriented, and tireless. Forest Supervisor Loren Bishop prized these qualities, to judge from his decision in 1923 to name Conarro the Allegheny’s first (and sole) district ranger.

Four years later, Conarro and his family headed for the Ouachita National Forest in western Arkansas. The environment was unlike anything he had encountered before, and the workload was challenging. As the forest’s Assistant Supervisor, he took on administrative responsibilities that included the budget, personnel, and fire control, among other duties. Conarro took on those same responsibilities in 1931 when he made a lateral move to the Cherokee National Forest as its assistant supervisor—and received this shout-out from Joseph Kircher, the southern regional forester, in the press release announcing the appointment: “His skillful attack on fire control problems and his grasp of fire prevention work won for him the unstinted praise of his superiors.”[1] Fire management would be a recurring theme over the rest of his career.

Surely that commendation figured into Kircher’s 1933 decision to tap Conarro to establish the Mississippi National Forests. Less than 24 hours after the Conarro family arrived in Brookhaven, Mississippi, Supervisor Conarro met with Kircher to review land-ownership and boundary data, and to discuss next steps.

The first of these was political. Purchase units like the Homochitto needed initial approval from the relevant county boards of supervisors, which the Mississippi legislature had stipulated in 1926 when it granted the federal government the right to approach landowners in the state. Another prerequisite was that the National Forest Reservation Commission must approve all purchase units before funding would be released. The commission was established after passage of the Weeks Act in 1911, legislation that enabled the federal government to purchase acreage in mountainous watersheds in the eastern United States. The 1924 Clarke-McNary Act expanded the commission’s writ to include once-forested, now-denuded tracts of land. Mississippi certainly qualified. After inspecting the Chickasawhay Purchase Unit, for example, Conarro noted he had “never viewed an area so large with so much devastation. Nearly 100% of the area I saw that day had been burned over in recent months.”[2] His work was cut out for him.

It helped, however, that the state’s congressional delegation gave Conarro its robust support. Senator Pat Harrison, Senate finance committee chair, earmarked funding for the National Forest Reservation Commission and to underwrite 34 units of the Civilian Conservation Corps in Mississippi. Conarro supervised 25 CCC encampments, whose enrollees planted millions of seedlings, built trails, bridges and roads; and stabilized deep gullies. (They also planted kudzu, but that’s another story). Representative Wall Doxey, a member of the commission, was such an avid supporter that he overrode Forest Service objections to the establishment of the Holly Springs National Forest, an intervention that Conarro approved: “I personally believe that this Unit meets all of the Weeks Law and the Clarke-McNary Amendment requirements as well or better than any other Purchase Unit” in the state.[3]

After countless land surveys, innumerable meetings with county supervisors and other public officials; after non-stop negotiations with landowners and financial institutions; and after drafting myriad land purchase agreements, Conarro and his indefatigable staff had done what in August 1933 must have seemed daunting. Over the next eleven months, Conarro recalled, “we had examined, and the National Forest Reservation Commission had approved, land purchases in excess of 600,000 acres. This was and still is, the largest area ever purchased, or under purchase agreement, by any one Forest in such a short period of time.”[4] The National Forests of Mississippi were now fully realized.

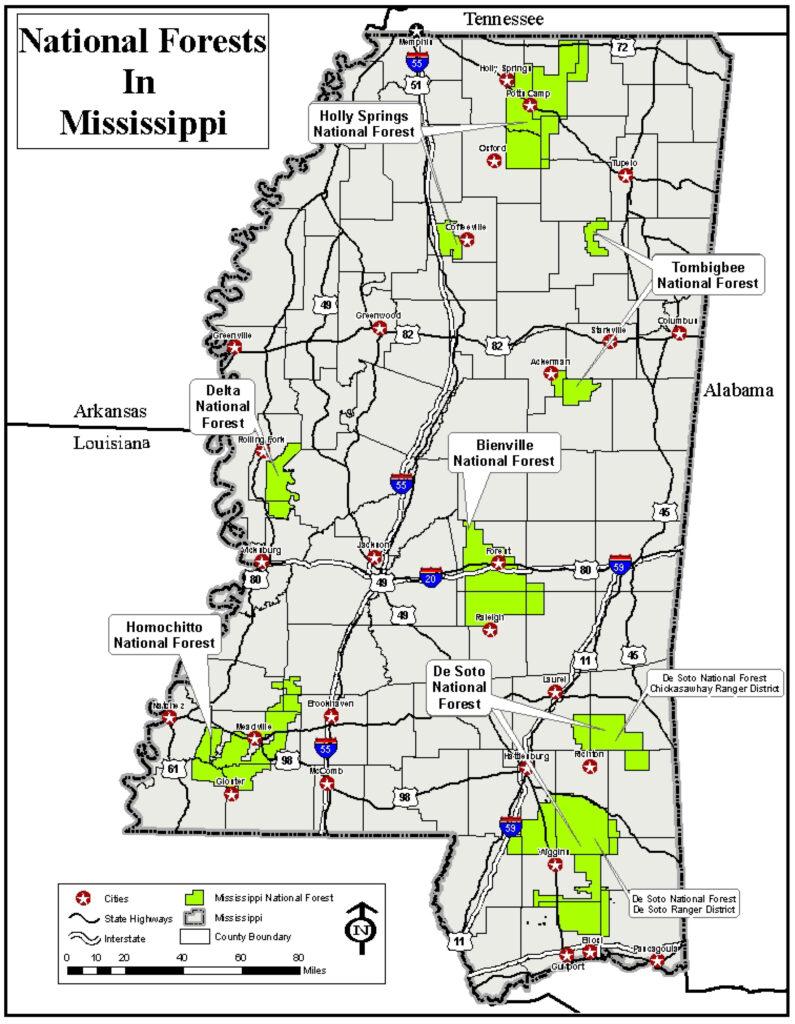

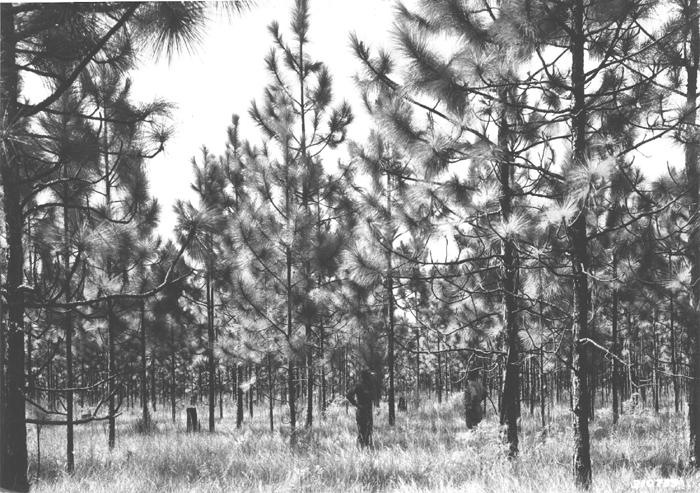

The land would regrow, too, the result of natural regeneration, CCC-developed plantation pineries, and, in another Conarro initiative, the reintroduction of fire to nurture longleaf pine forests and grasslands. In 1935, he conducted the first Forest Service–approved controlled-fire research on the DeSoto National Forest, the success of which led him to coin a new term for this process, announced to his fellow foresters in the Journal of Forestry: "prescribed burning."[5] By 1962, when he retired from the Forest Service and returned to Mississippi as a forestry consultant, fire was routinely deployed on the six national forests he had helped create. Those forests—the Bienville, Delta, DeSoto, Holly Springs, Homochitto, and Tombigbee—together comprise 1.2 million acres of impressively diverse forest ecosystems, from pines in the south to hardwoods in the north, bottomland hardwood forests in the west to restored farmland in the east.

Imagine Ray Conarro’s pride in this place.

About the author: Char Miller is the W. M. Keck Professor of Environmental Analysis and History at Pomona College, and author of Natural Consequences: Intimate Essays for a Planet in Peril (1922), Gifford Pinchot: Selected Writings (2017), and America’s Great National Forests, Wildernesses and Grasslands (2016). This post is adapted from Miller’s forthcoming article on Conarro in Forest History Today.

NOTES

[1] Joseph C. Kircher, press release, June 26, 1940, 2; in U.S. Forest Service Biographical Files, Forest History Society, Library and Archives.

[2] Ray M. Conarro, “The Beginning: Recollections and Comments,” 13 [PDF]; in Alfred P. Mustian, Jr. Papers, 1907–1985, Forest History Society, Library and Archives.

[3] Conarro, “The Beginning,” 24.

[4] Conarro, “The Beginning,” 2.

[5] Raymond M. Conarro, “The Place of Fire in Southern Forestry,” Journal of Forestry, 40:2, February 1942, 131.