Essay: History of Urban Forests

Colonial Woodlots

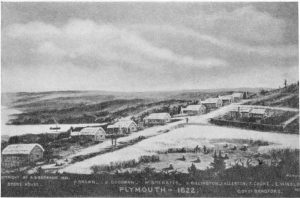

Figure 1: Plymouth in 1622. Drawing by A.S. Burbank, from American Conservation, 1935

Although the United States government did not recognize urban forestry by name until 1978, the practice of cultivating and maintaining a communal forest for the benefit of all is as old as the nation itself. The practice began on a cold November day in 1620 when a band of wet, ill-nourished Mayflower passengers staggered up on the shores of an abandoned Indian settlement and renamed it Plymouth. By the end of the first year, the Pilgrim elders had designated land for house lots, the meetinghouse, parsonage, and cemetery, a central grazing commons, and the first "urban forest." The woodlot, as it was called then, was to be held in common-owned and maintained by all-to provide the raw material for heating, cooking, shingling, clapboarding, furnishing, fence-laying and road building, and the habitat for game.

Records of the early New England town meetings show they hired tree wardens who enforced the rules. "Every man that is an inhabitant of the Towne shall have Liberty to take any timber off the Common for any use in the Towne [provided] so they make not sale of it out". (Braintree, MA) "If any man shall find a Bee tree in any of our commons and shall sett the two first letters of his name on it faire in vew it shall be accounted his pries." (Farmington, CT) Every parsonage was assigned a ministerial lot, every school had meadow and forest. Even the almshouses had woodlots, enabling the poor to support themselves selling peg timber, shingles, posts, rails, bark and ship timber.

City Street Trees

By 1850, there were 20 million Americans, 80% of whom were living much the way the pilgrims did, entirely off the land. Over the next 70 years, rural towns would become cities, and cities would become metropolises and 70% of Americans would be making a living in city shops and factories. Reaction to urban conditions generated new ways of thinking about trees.

From Henry David Thoreau, writer and philosopher came another sentiment: "We hear of cow-commons and ministerial lots, but we want men-commons and lay lots, inalienable forever. Let us keep the New World new, preserve all the advantages of living in the country. There is meadow and pasture and wood-lot for the town's poor. Why not a forest and huckleberry-field for the town's rich?" (Journal of Henry David Thoreau, Oct. 15, 1859.)

Figure 2: The Sheep Meadow in Central Park, with the Solow Building. Photo courtesy of www.wirednewyork.com

Post War America

Frederick Law Olmsted, landscape architect of New York City's Central Park, believed that trees and vegetation enhanced the morale and counteracted the anxieties of city life. A city park, he said, was to "provide a natural verdant and sylvan scenery for the refreshment of town-strained, men, women, and children." J. Sterling Morton, founder of Arbor Day, said on the 30th anniversary of the day in 1902 "Arbor Day is now one of the recognized institutions of the country. Every spring it directs attention to the interest that attaches to trees and gives instruction respecting the kinds and their cultivation." It was in this climate that many states passed bills allowing communities to use public funds for the planting trees. The cost of maintaining them however, wasn't provided for. In 1915, someone speaking for the "Trees of Newark" published a plea to change the policies (or lack of policies) that "...allow horses to bite us, linemen to cut us, builders to maul us, vandals to hack us and borers to tunnel us." At the time American troops were shipped oversees for WWI, urban trees suffered from horse bite. When the GI's returned after WWII, automobiles were the major threat to urban trees. With President Eisenhower's expansion of the interstate highway system through cities and towns, the easiest place to lay new road bed was through the preserved urban woodlands and parks. The increase in roads made it easier to abandon the city for the shady suburbs. This urban flight left the core of the city to languish along with its street trees.

In the mid 60's, urban centers contained bankrupted municipal governments, abandoned neighborhoods, crime, noise, pollution, and decreasing population. Ladybird Johnson voiced concern about urban blight and initiated a beautification campaign . "Getting on the subject of beautification is like picking up a tangled skein of wool," she wrote in her diary, "all the threads are interwoven, recreation and pollution and mental health, and the crime rate and rapid transit, and highway beautification, and the war on poverty, and parks-national, state and local." Following President Johnson's White House Conference on Natural Beauty, the U.S. Forest Service began championing a new kind of forestry specializing in the needs of Urban and Community Forests. The 1978 Cooperative Forestry Assistance Act officially recognized that urban and community forests "improve the quality of life for residents; enhance the economic value of residential and commercial property; improve air quality; reduce the buildup of carbon dioxide; mitigate the heat island effect in urban areas; and contribute to the social well-being and sense of community." For the first time, the U.S. government allocated federal funds to cultivate and maintain city trees. Ten years later, President Reagan again articulated the benefits that trees yield the nation "..in concrete deserts we lose touch with the real world of trees, birds, small animals, and plant life. We each need outdoor recreation opportunities close to home where they can be a part of our daily lives."

Urban Forestry

Since the passage of the Cooperative Forestry Assistance Act, research has proved statistically what many people feel instinctively-that cultivating and maintaining urban forests yields measurable aesthetic, economic and environmental benefits to Americans.

Economic Value

The city of Tallahassee, Florida, urban planners found that in one year, the existing tree cover saved the city $760,000 in energy savings, $2.6 million in storm water runoff reduction, $1.06 million in air pollution removal, and kept 784 tons of carbon dioxide out of the global atmosphere.

- Social Value

Inner city neighborhoods in North Philadelphia and Baltimore found that forestry helped soothe social problems. Clearing vacant lots of rubbish and creating mini-parks of flowers and trees united neighborhoods, eliminated eyesores and ran off drug dealers. They found that the psychic wounds of urban decay were cheaper to prevent than to repair. - Ecological Value

With the delineation of greenways preserving streams in new neighborhoods came an increase in the biological diversity of plants and animals. Increased biodiversity leads to increased ecosystem function. Increasing the number of functioning ecosystems is the only way to increase the manufacture of clean air, clean water, and clean soil. - Aesthetic Value

Hearing wood thrushes, watching chipmunks and observing rat snakes strengthens the imagination of children and diverts the attention of work-worn adults. The visual beauty of nature is key to the quality of life for all people.

As a result of research on the value of trees, the practice of urban forestry is no longer reserved for state and federal foresters. Urban forestry is now being considered by zoning, planning, parking, transportation, and city hall. In the future, we can expect to see Geographic Information Systems synthesizing data from aerial photographs, satellite images, and ecological surveys to generate efficient and precise strategies for planting and maintenance of urban and community forests. We can also expect to see an increased role for the citizen in the care of the nation's trees. By learning the history of forest policy, we become better able to draft and support forest policy that treasures urban and community forests.

We find ourselves again, like the Plymouth pilgrims, practicing stewardship over a woodlot that is co-owned and co-maintained by the entire community. In Plymouth "(a)ny inhabitant of the Towne has the liberty to take of the timber." But in our urban forests, instead of limbs and branches, we take the pleasures and benefits bestowed upon us by the trees.