Division and Restoration: A Brief History of Forestry on the Quinault Indian Reservation

Tweet ShareIntroduction

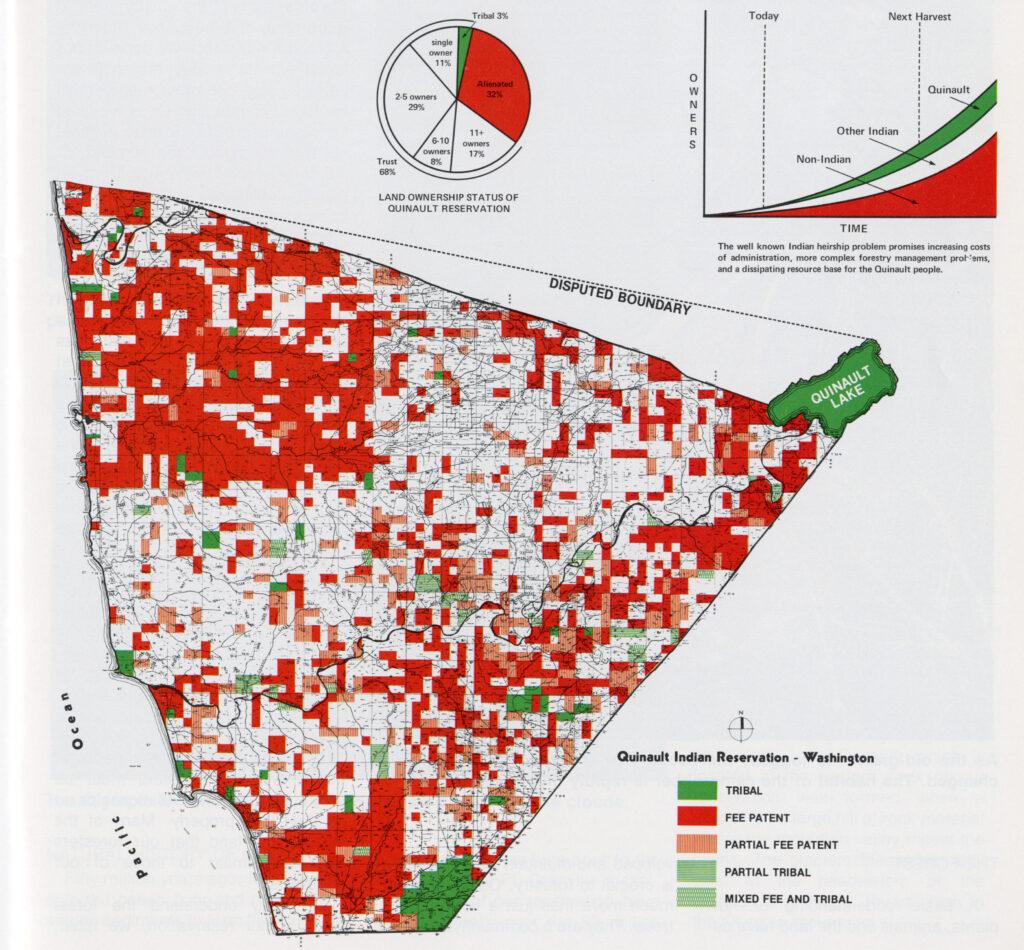

Comprised of 208,000 acres and located on the Pacific Ocean and Olympic Peninsula of Washington, the Quinault Indian Reservation contains extensive coastal forests that have always been central to the tribe’s culture, subsistence, and economy. Since the 1920s, managing timber on these forests has been challenging and mired in controversy, involving a complex relationship with the United States over allotment of communally held land given to individuals in 80-acre parcels, logging contracts and practices, and fiduciary trust responsibilities.

Recurring conflicts between American governmental officials came to a head with the Supreme Court case United States v. Mitchell, which found the United States liable for financial damages due to breach of fiduciary trust responsibilities in the management of Quinault forests. The case was originally filed in 1971 as Helen Mitchell v. United States by a group of allottees alleging mismanagement by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, which oversaw forest management policies and distribution of the land. As the case worked its way through the courts, historians Elmo Richardson, Harold K. Steen, and Robert E. Ficken compiled documents about the history of forest management on the reservation, now preserved as the Quinault Indian Reservation Collection at FHS, and used them in their 1977 book The Bureau of Indian Affairs and Forestry on the Quinault Indian Reservation: A History, published by the Forest History Society and the U.S. Department of Justice. This exhibit draws from those and other materials. We want to thank Gary S. Morishima, Natural Resource Technical Advisor of the Quinault Management Center, for reviewing the text. Any errors are the responsibility of the Forest History Society.

Contents

The Land of the Quinault

Early History of Government Interference

The Dawes Act and Allotment

Commercial Logging and Forestry Mismanagement

Helen Mitchell v. The United States I and II

Notes

The Land of the Quinault

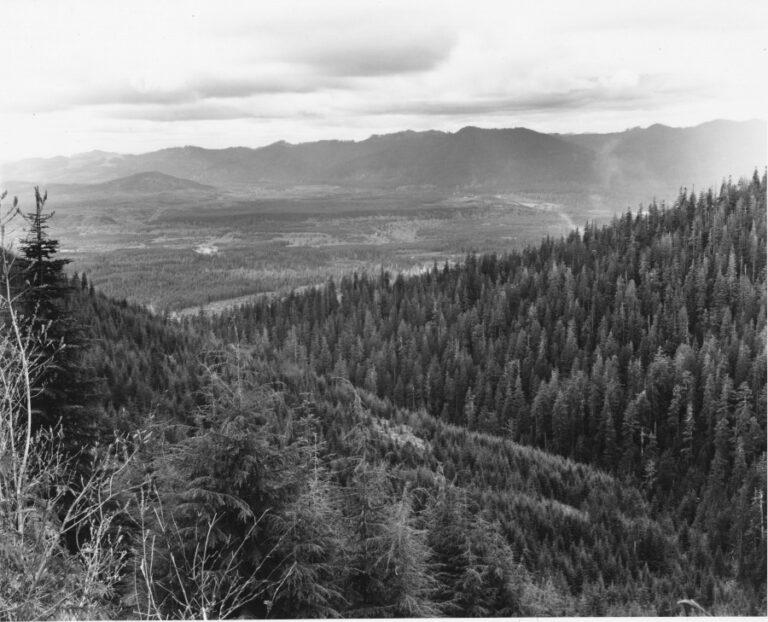

Millions of years ago, glacial movement and volcanic activity shaped the four distinct land types that make up today’s Quinault Indian Reservation: the glacial plane, broad valleys carved by rivers, a marine terrace (coastal land bound by sea cliffs and glacial gravel deposits), and mountainous uplands.[1] Quinault lifeways were closely tied to forests and rivers. Forests provided wood for housing, fuel, canoes for transportation and access on rivers and the ocean, foods and medicines, habitats for wildlife, places for spiritual renewal, and materials for clothing and artistic expression.

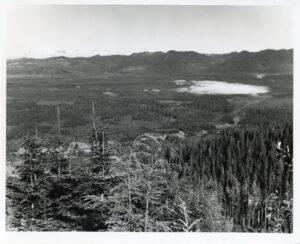

Eastern portion of the Quinault Indian Reservation from Nielton Point on the Olympic National Forest. Nielton is visible at the foot of the mountain, in the right foreground. Amanda Park, at the outlet of the Quinault Lake, is hidden under the low lying fog bank. The distant ridge is partially on the reservation. The boundary, appearing as a diagonal line of demarcation between uncut timber on the national forest, and cut over on the reservation, climbs over the ridge toward the left. Lone Mountain, visible below the skyline in the left background, is within the reservation boundary

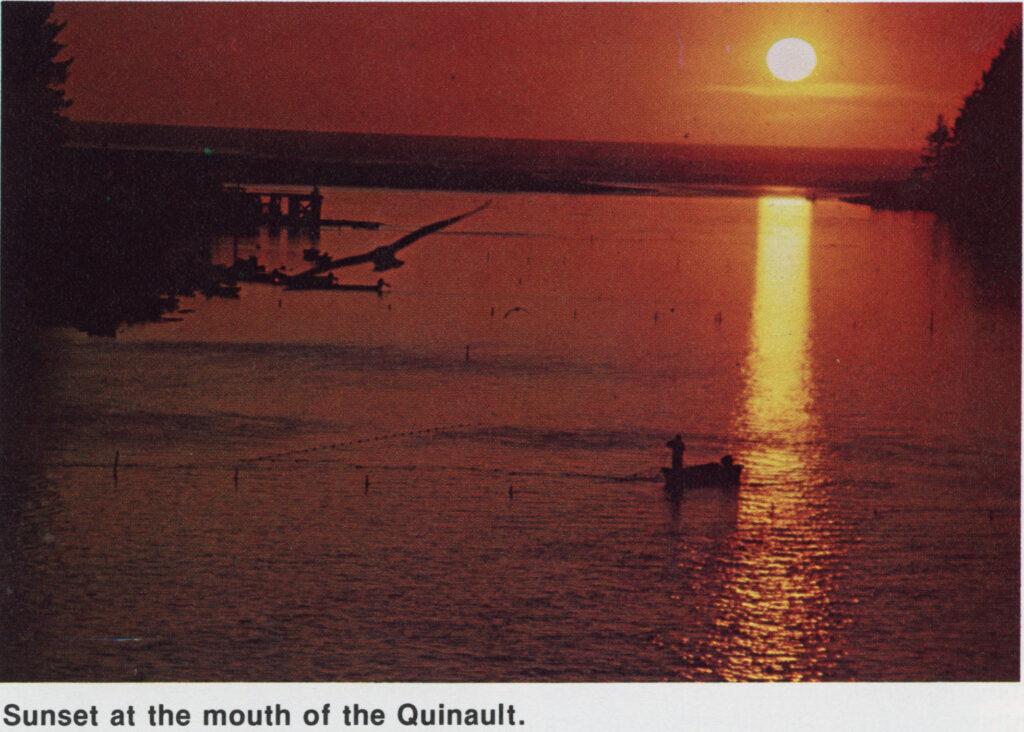

The two major rivers with headwaters in coastal rainforests, the Quinault and Queets, traverse the reservation and produced abundant runs of Chinook, Coho, Chum, Steelhead, and Blueback (sockeye) salmon, which had sustained the Quinault culture and economy for thousands of years.[2] Maintaining healthy forests has always been critical to maintaining healthy fisheries, and in turn, a healthy culture.[3]

The Quinault lived in longhouses and crafted canoes—an important mode of transportation for a river- and ocean-dependent people—made from the western redcedar found in the area.[4] They used tools, such as wedges, chisels, and mauls to harvest cedar. They chose trees close to waterways to cut, and worked collaboratively to retrieve and transport the logs efficiently. The Quinault view the western redcedar tree as the “tree of life,” because of its significance in sustaining lifeways (even the bark was used for clothing and basketry), and its durability. But trees were not just resources; they were relatives with conscious spirits that needed to be treated with respect. Felling a tree began with prayer—the tribesperson speaking formally to the tree and “asking permission to down it.”[5]

Beginning in the early 20th century, western redcedar, western hemlock, Sitka spruce, and Douglas fir were the most common species logged, although Pacific silver fir, western white pine, red alder, cottonwood, and big leaf maple were also harvested.[6] Stumpage from timber sales of these species provided income and employment—for both Quinault and non-Quinault land owners. That distinction of who owned and who controlled the land would become the source of controversy.

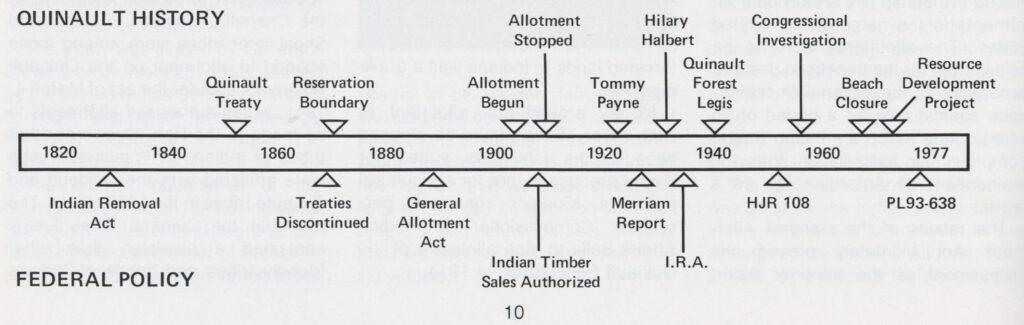

Early History of Government Interference (1830–1887)

The Quinault tribe lived on their coastal homelands for thousands of years before Spanish explorers first spotted Mt. Olympus from their ships in 1774.[7] But the roots of Helen Mitchell’s case filed two centuries later only stretch back to the Native American land policies of the Andrew Jackson administration and the Indian Removal Act of 1830. At the time, the American government sought to remove Native peoples from the land to allow for Anglo settlement and development. This pattern repeated itself in the Pacific Northwest. Pressures to open land for non-Indian settlement mounted soon after the establishment of the Washington Territory in 1853. Two years later, after months of negotiations with the territorial governor, the Quinault, Quileute, Queets, and Hoh tribes agreed to the Quinault River Treaty on July 1, 1855.[8] The Chinook, Chehalis, Cowlitz, and Shoalwater tribes were left out of the deal. The governor had forced the negotiations to be conducted in a Native American dialect that many Quinault tribespeople did not understand.[9] Under the treaty, the tribes ceded claims to millions of acres of land, reserved rights to fish, hunt, and gather on open and unclaimed lands; in return, the United States pledged to set aside reservations for exclusive tribal use and occupancy and to provide services for health care, education, and other considerations.

The negotiations leading to the Quinault River Treaty marked the beginning of a long and fraught relationship between the Quinault and United States government. Treaty making was discontinued in 1871, after Congress passed an updated version of the Indian Appropriations Act, which holds that no Indian nation within the borders of the United States would be recognized as independent.[10] In 1873, President Grant signed an executive order that set the present-day boundaries. Under its authority, the many and various tribes across much of Washington were to move onto the Quinault Reservation, though not all tribe members did.

Quinault Lake and background mountains through a screen of hemlock reproduction. Note the lone Douglas-fir seedling. This area, in NE/4 Sec. 26, T. 23 N., R. 10 w. was logged in 1952. Such areas may become more valuable for summer home sites than for timber production. 3/4/1959.

An area much smaller than the Quinault Reservation was originally set aside, but it was later expanded to cover an area deemed sufficient for hunting, fishing, and gathering activities and was communally owned to help sustain tribal lifeways. The expanded reservation encompassed roughly 220,000 acres of land and Lake Quinault, but a surveying error reduced the area contained by reservation boundaries to 190,000 acres. In 2008, the North Boundary Restoration Act (PL 100-638) restored 18,000 acres to the Quinault Nation, bringing the total to 208,000 acres.

The Dawes Act and Allotment (1887-1934)

In 1887 President Grover Cleveland signed two laws that would become critical to the Quinault forests story: the Dawes Severalty Act (also called the General Allotment Act) and the Tucker Act.[11] The Tucker Act waived the federal government’s sovereign immunity with respect to certain lawsuits. The importance of this law, and the related Indian Tucker Act of 1946, which allowed Indian tribes to sue in the Court of Claims, wouldn’t come into play for nearly a century after its passage.[12]

The Dawes Act, however, had an immediate impact. It aimed to assimilate Native Americans into Anglo-European culture and make them into farmers by dividing communally held reservation lands into individually owned allotments.[13] The size of allotments varied, depending on the land types involved. Under the terms of allotment, lands were to be held in trust by the United States; lands not allotted were to be opened for non-Indian settlement. The Quinault, however, believed that people could inhabit the land and utilize its resources without individual property ownership. To Anglo-Americans, ideas of shared land and common property marked native peoples as primitive and uncivilized. They dismissed the Quinault’s cultural concepts of property, communal sharing, and stewardship. Additionally, the Indian view of land, which emphasized the “spiritual worth and cultural heritage,” conflicted with those of American governmental agencies, which sought to reap economic benefits from resources.[14]

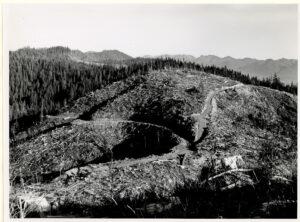

View to the east of clearcut block from State lookout on allotment of Florian Kjos No. 1229, Section 11, T. 23 N., R. 11 W. Clear-cut block in left middle distance is within the Olympic National Forest. Rugged, snow-flecked mountains in the background are also on the Forest, South of Quinault Lake.

The first allotments on the Quinault Reservation were made in 1905. Seven years later, practically all of the agricultural and grazing lands had been allotted. Warren Shale writes, “Within the next 45 years, Indians around the nation had lost nearly two-thirds of the land that they had originally had reserved for them through treaties.”[15]

Native Americans who qualified for allotted land applied to Bureau of Indian Affairs officials for title.[16] On the Quinault Indian Reservation, BIA officials allotted land with limited agricultural value or benefit. Additionally, BIA officials failed to recognize that allotments with swamp or prairie land would earn less logging revenue.[17] Unequal and scattered distribution of Quinault Reservation land contributed to wealth disparities.

The dense forests that covered the Quinault Reservation stood in the way of the federal objective of converting the people into farmers. The BIA’s main charge was not to provide for sustained forest management, but rather to clear the land for agriculture, despite the fact that much of the soil on the Quinault Reservation is unsuitable for crop farming due to its “coarse” and “gravelly” nature.[18]

Ultimately, the 190,000-acre Quinault Reservation was broken up into 80-acre allotments owned by 2,340 individuals, and the communal land base was reduced to small village locations. In this chasm between belief systems was laid the foundation for a series of legal clashes that the Quinault would face from the federal government, the U.S. Forest Service, and the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Allotment on the Quinault Reservation was fraught with litigation and legislative action. BIA’s director of forestry J. P. Kinney posited that soil on the reservation was not fit to farm.[19] After years of resistance towards Quinault pleas to amend the allotment system, Kinney stopped allotting in 1914, after all the land suitable for agriculture had been doled out and only heavily forested lands remained.[20] Kinney was at times unsympathetic toward the struggles of Native Americans, even saying later in life, “There’s been too much talk about the Indian losing his land, as if the white man were grabbing it away from him.”[21]

Pressures quickly mounted to reopen the Quinault Reservation land to allotment. In 1922 Tommy Payne, a member of the Quileute Tribe, a signatory to the Quinault River Treaty, successfully sued the government to obtain an allotment. In 1924, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that those lands capable of being cleared and cultivated could be allotted. In a subsequent 1931 case, the U.S. Supreme Court declared in Halbert v. United States “that non-resident Chehalis, Cowlitz, and Chinook Indians were entitled to allotments on the Quinault Reservation. This decision to allow non-residents to receive allotments, together with the ruling on allotting timbered lands, brought a rush of applications. By 1934, 2,340 trust allotments were granted and the reservation lands were exhausted, except for a very few acres.”[22] Over time, individually owned allotments became fragmented by heirship processes and became owned by undivided property interests held in fee and trust title. Fragmented lands make forest management on a landscape-scale challenging. Fire response and cutting practices remained contentious debate points between BIA officials, logging companies, and Quinault.

Allotment generated bureaucratic nightmares and ecological neglect under vacillating federal Indian policy. Shale describes the BIA’s approach to land management as “forestry by omission.”[23] Only 20 percent of allottees visited their holdings, allowing the forest to fall into an unhealthy state, unproductive for the growth and sale of timber.[24]

Commercial timber sales between Quinault allottees and logging companies began near the time of the Tommy Payne case, spanning 1920 to 1923.[25] Aloha Lumber, M. R. Smith, Ozette Railway, and Hobi Lumber companies conducted early logging ventures on reservation land.[26] Kinney and BIA officials divided reservation land into logging units, avoiding negotiation between individual allottees and lumber companies. This secured favorable contracts with lumber companies and increased revenue for the Quinault. Despite financial benefit for most allottees, others tribespeople, like William Mason, refused to sell with allotment groups.[27]

Kinney, seeing the positive effects of halting the allotment system, began to advocate for its nationwide abandonment.[28] Kinney and colleague Henry B. Steer wrote articles critical of forestry-by-allotment.[29] In 1934 their efforts came to fruition, when the Indian Reorganization Act (or Wheeler-Howard Act) was passed, which provided for recognition of tribal governments, halted allotments, required sustained yield forestry, and authorized a land

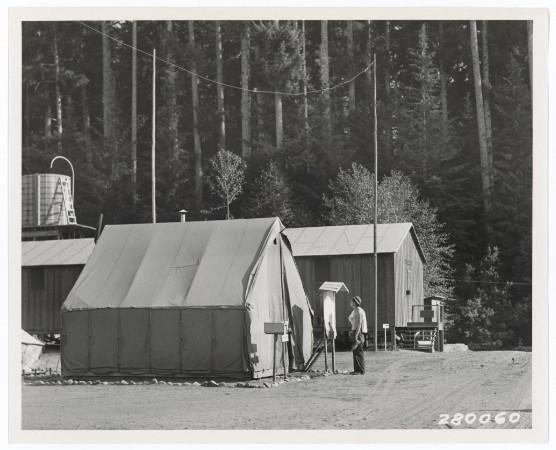

Civilian Conservation Corps Quinault camp. National Archives Identifier: 7005021. From National Archives at College Park.

consolidation program to try to undo damage resulting from allotment policies and practices. It was intended to conserve and develop Indian lands and resources and increase self-sufficiency in other ways.[30] However, nearly all of the Quinault Reservation land had already been allotted, and the forest health decline accelerated.[31]

In the 1920s, commercial logging companies clearcut entire watersheds and left large amounts of slash in their wake. After several dry summers in the late 1920s and early 1930s, the slash left behind provided tinder for a decade’s worth of forest fires.[32] The Great Depression’s downward pressure on national lumber prices pushed logging companies to cut corners but not harvest rates.[33] Kinney also saw low wages and high turnover rates at logging companies as major influencing factors for poor forestry practices.[34] He feared that foresters might commit arson and start forest fires in order to create employment opportunities.[35]

Commercial Logging and Forestry Mismanagement (1934-1971)

Some federal New Deal programs, such as the Civilian Conservation Corps, helped during this period of economic uncertainty.[36] Additionally, with the appointment in 1933 of John Collier as Commissioner of Indian Affairs, the federal government began to shift towards encouraging self- sufficiency for Native American tribes. Collier, along with Kinney, advocated ending the policy of allotment. Yet, despite national political attention and relief programs, Quinault Reservation forests still suffered.

This cutting block on Allotment 1568 in Sec. 20 T. 22 N., R. 12 W., was logged in 1957 and will soon be relogged for salvage. Note snag tops of dead and partially dead cedars in uncut timber across ravine. Because of the great volume of such dead material, the soft and brittle cedar wood, the massive size of cedar trees and powerful machinery needed to skid the big logs, wreckage such as this is unavoidable. This is a good logging job. February 18th, 1959, Quinault Indian Reservation.

Clearcutting was the standard logging method from 1922 on, but the BIA instituted selective logging in the early 1930s.[37] Frequent forest fires and deteriorating ecological health motivated the BIA to push for change.[38] In selective logging, foresters only logged large, mature trees, which was seen as an ecologically sound practice.[39] BIA foresters adopted sustained yield as the standard goal in 1936, and pressed for planting tree seedlings in order to reforest, but sustained yield was not implemented on individually owned allotments.[40] This difference would contribute to the establishment of the Quinault Experimental Forest in the southeastern portion of the reservation. Yet, despite potential ecological advantages, the Quinault resisted these proposals, citing poor standards for selective logging. The combination of selective logging and sustained yield slowed revenue streams generated from allotments.[41] Additionally, the Quinault now generally distrusted the U.S. government.[42]

Despite forest mismanagement and decreased revenue, the 1930s were an important period for the development of Quinault self-governance and autonomy. Following the passage of the Wheeler-Howard Act, which enabled a greater degree of self-government, they established a tribal council at Taholah.[43] In January 1936, the Quinault, motivated by tense relations with logging companies and BIA officials, insisted to the Department of the Interior upon their right to clearcut land on the reservation.[44] Members of the Quinault tribe went to the Interior Department’s national headquarters in search of either a modified contract or full autonomy in determining their forestry practices.[45] Little came of this meeting, but this symbolic request for federal government intervention marks an important milestone in Quinault Reservation forest management history.

In April of 1936 the Quinault consented to a renegotiated agreement that aided contract and stumpage pricing for Quinault, but it did not change selective logging practices.[46] In 1939 groups of Indians across the country began to file federal court cases challenging the BIA’s ability to use lumber companies’ preferred logging practices.[47] In Eastman v. United States (28 F Supp. 807(1939)), Judge Yankwich ruled that the United States could not impose selective logging restrictions on harvesting allotment timber: “There is no warrant in this section for a policy of timber conservation, which, no matter how laudable and socially beneficial, does, in fact, diminish an Indian allottee’s full enjoyment of his fee, as to a matter not limited by the allotment or by law.”[48]

The years immediately following World War II did not immediately bring economic relief to the lumber industry.[49] Furthermore, the Quinault felt frustrated by BIA paternalism.[50] National bipartisan political efforts to seek compensation for damages and promote tribal autonomy and authority came to fruition in 1946 with the creation of the Indian Claims Commission.[51] The commission would hear potential grievances tribes had against the United States government. It also aimed to bolster independent financial management of businesses on reservations.[52] This dramatically decreased BIA funding from Interior for land management, while increasing individual allottee autonomy for land sales and timber contracts.[53] Despite the increasing public and governmental focus on remedying paternalistic federal legislation related to Native American reservation land, the BIA-Quinault relationship remained tense during the 1940s and 1950s.

While the Wheeler-Howard Act aimed to alleviate tensions between Native American groups and the federal government, timber sales remained in units of allotments, and BIA officials still sought to benefit individual allottees rather than the Quinault nation as a whole.[54] The BIA pursued 30,000-acre timber sales for the Taholah and Crane Creek logging units, which were signed in 1952.[55] However, these timber sales drew skepticism from Capitol Hill. Warren Shale writes in Portrait of Our Land, “Serious questions regarding the BIA’s administration of the Taholah and Crane Creek contracts eventually resulted in Congressional investigations during 1956–1957.”[56] The hearings resulted in a change of leadership at the BIA, the requirement of tribal approval of timber sales, and modified timber pricing procedures. But debate about allotments and their role in timber sales continued.[57]

The impact of a new federal policy called Indian termination began exerting its force on tribes during the 1950s as the United States sought to divest itself of obligations (in the form of federal aid) it had undertaken pursuant to treaties. The policy, intended to assimilate Native Americans into mainstream American society with some speed, also ended the federal jurisdiction of trust lands, opening it to sale to non-Natives. On the Quinault Reservation, timber companies gained ownership of much of the land still containing timber through supervised sales of allotments. Many of the allottees believed that they were selling timber, but not the land. By the 1970s, the Quinault Indian Nation would own only three percent of its land base, and nearly 32 percent would be owned by large, outside timber companies.

This history of land ownership tenure resulted in a divided Quinault Reservation in land ownership, tribal loyalties, and governance. The article “Logging History of the Quinault Reservation–A Reprise” notes that “by the end of the 1950s, in essence, the Reservation had become akin to a cluster of 80-acre fiefdoms, a number of whose owners rejected any authority over them, even that of the Federally recognized Tribal government.”[58] Compounding matters was the fact that BIA controlled the logging contracts, which did not allow for protection of streams and rivers but did allow logging right down to the waterway. Allotments and further subdivision of land through fractionation into undivided property interests, and continued mistrust of the BIA, caused deep-seeded disparities that would be exacerbated by increased instances of environmental damage from logging practices and fires during the following decades.

According to Shale, “Our streams have been clogged by logging debris; our salmon spawning grounds have been choked by silt from logging roads; and mountainous accumulations of slash, brush fields, vast clearcuts and poor tree-stocking still characterize our lands” (Shale, 32).

Photo of Helen Mitchell from the Seattle Daily Times, from “Land is Life: Quinault Indians now run reservation with firm hand” by Don Hannula from September 26th, 1971.

Helen Mitchell v. The United States I and II (1971-1983)

As environmental conditions continued declining due to mismanagement, poor management, improper logging techniques, and the political wrangling that exacerbated all of these, tensions between the Quinault, BIA, and logging companies climbed towards their apex. In 1971, Quinault tribe members blocked the Chow Chow Bridge, used to cross the Quinault River to access the Taholah Logging Unit, and tribal leaders placed barricades on various roads, preventing logging companies from conducting business.[59] It proved a turning point. Only when logging companies and the BIA agreed to increased stumpage rates did the Quinault stop impeding access to reservation land.[60] Other political demonstrations and assertions of tribal sovereignty continued to occur into the mid-1970s.[61]

Quinault tribe member Helen Mitchell owned multiple allotments on Quinault land, owned her own logging company, and was concerned with what had been happening on the land. She also served as a chair of the Quinault Land and Forest Committee and as recording secretary of the National Congress of American Indians.[62] The same year the Chow Chow Bridge was blocked, Mitchell filed a lawsuit that would have massive implications for the Quinault Reservation land.[63] The BIA had charged Mitchell with using improper logging techniques.[64] Motivated by the potential fines, Mitchell traveled cross-country and secured legal representation in D.C. She planned to sue to BIA and United States government for land and forest mismanagement and breach of fiduciary trust responsibilities after having entered into long-term timber sale contracts.

Helen Mitchell represented a small number of allottees who profited from timber on Quinault Reservation land. But in order to secure the legal contract and legally act for allottees, she needed to garner wider tribal support.[65] She struggled to get many responses, only securing a majority of 650 people (out of 1200 allottees) years after first traveling to find legal aid.[66] After securing support from several allottees, Mitchell filed suit in 1971 under the Tucker Act and Indian Tucker Act in the United States Court of Claims.[67] She and the other allottees sought reparations for mismanaged logging operations, poor-quality land and timber, failure to replant trees, and contractual shortcomings by logging companies.[68]

BIA officials found themselves in a Catch-22. Richardson observed in his history of the BIA and Quinault forestry, “The government was at once defendant and council for

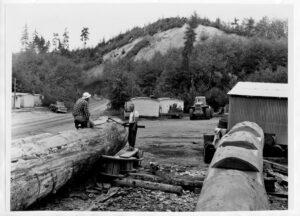

Here, at Mayer’s Bros. Logging Camp, on the Olympic National Forest, James Lesman “takes five” in his labor of hewing new skids for a donkey, while visiting with Jim Ross, forester, of the Hoquiam Sub-Agency staff. Note the hewing adz, the handle of which is gripped in Mr. Lesman’s right hand. Note also, the chain power saw on the ground between the skids. These heavy skids are from high quality Douglas-fir trees, purchased from the Olympic Forest. August 13, 1963.

the plaintiffs.”[69] Some sympathetic BIA employees had encouraged Mitchell to sue the government because the agency would have to offer access to institutional archives for legal research during the lawsuit.[70] In January 1970 hired a law firm, although it did not file until 1971.[71] The Quinault saw the BIA as part of a monopolistic and manipulative relationship with the logging companies, supposedly favoring corporate interests over Native American land preservation and revenue.[72] Furthermore, the BIA was caught between continuing to serve the Quinault by negotiating contracts on behalf of allottees and adhering to the legally and financially binding contracts they had entered into with lumber companies.[73]

In Mitchell et al. v. United States, the Court of Claims ruled in favor of the plaintiffs, citing the Tucker Act, Indian Tucker Act, and the General Allotment Act in particular.[74] In the eyes of the court, the General Allotment Act created a “fiduciary duty on the part of the United States, as the holder in trust of the lands, to manage the timber resources appropriately.”[75] Yet, legal battles with the United States government would continue for another next six years, reaching the Supreme Court on two occasions.

Following the Court of Claims ruling in 1977, the United States appealed. The ruling in The United States v. Helen Mitchell (1980, or Mitchell I), was a setback for the Quinault plaintiffs. Writing the majority opinion, Justice Thurgood Marshall argued that the General Allotment Act “created only a limited trust relationship between the United States and the allottees that does not impose any duty upon the government to manage timber resources.”[76] In sending the case back down “the Court deliberately left the door open to continued pursuit of the claim under alternatives sources of law.”[77] The Court of Claims ruled again in favor of Mitchell, and the case returned to the Supreme Court.

When the Supreme Court addressed the government’s alleged mismanagement for a second time in 1983 (Mitchell II), there remained the need to answer the question “of whether forest allotments were in a different situation since other statutes imposed specific affirmative management duties on the United States.”[78] After reviewing legal language in the Tucker Act and General Allotment Act, the Court ruled in favor of Mitchell. Writing again for the majority, Marshall viewed the legislative precedent and financial wording in business contracts as indications that the U.S. had entered a trust relationship with the Quinault.[79] Ultimately the Supreme Court ordered the United States government to pay $26 million to Mitchell and Quinault allottees for mismanagement of timber contracts, land, and other damages.[80]

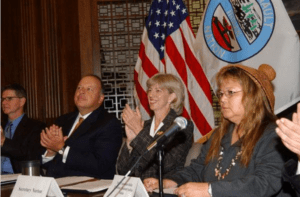

At a signing event for forest habitat protection pact, left to right: Edward Damich, Chief Judge of U.S. Court of Federal Claims; Thomas Sansonetti, Assistant Attorney General for Environmental and Natural Resources; Gale Norton, Secretary of the Interior; and Pearl Capoeman-Baller, President of the Quinault Indian Nation. From National Archives at College Park, MD

The payout from the Supreme Court case would have lasting positive effects for the Quinault, and for other tribes. In 1991, eight years after the second Mitchell ruling, the Quinault Allottees Association established two scholarships at Lewis and Clark Law School in Portland, Oregon, for students belonging to an ethnic minority, with priority given to those of Native American descent.[81] Furthermore, Mitchell II set a precedent for other tribes to file suit for similar cause. Cases such as Navajo Tribe of Indians v. United States, trust-relationships before the federal courts for resolution.[82]

Despite the lasting legal impact of Mitchell II, the ruling didn’t provide a panacea for the larger issues facing the Quinault Nation: environmental restoration, the need for sustained employment opportunities in lumber, shrinking population sizes, and an increase in the tribe’s median age.[83]

With passage of the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act (PL 93-638) in 1975, the Quinault Nation established its own forestry and fisheries management programs, which have expanded in scope and responsibilities under Self-Governance authorities. The Quinault Business Committee, an elected governing body, manages and maintains sources of income, like casinos, tourism, fisheries, and land and timber enterprises.[84] The North Boundary Act (PL 100-638), passed in 1988, not only restored nearly twelve thousand acres of land to the Quinault Nation, it also provided for revenues from the sale of timber from the restored lands to be used for land consolidation and improved forest management. Through self-governance and the management of its reservation forests by the Quinault Division of Natural Resources that adheres to their traditional beliefs, and an aggressive land consolidation program funded largely by timber revenues, the Quinault are beginning to reassert their centuries-old, nature-based culture today and to remediate for the damaging practices and policies of the United States federal government. The Mitchell cases helped make that happen by providing a legal foundation on which to build.

Forest History Society Resources

Harold Weaver Notebooks, Library and Archives, Forest History Society, Durham, NC, USA.

Notes

[1] Warren Shale, Portrait of Our Land: A Quinault Tribal Forestry Perspective (Taholah, Washington: Quinault Tribal Council, 1978), 14.[2] Shale, Portrait of Our Land, 7.

[3] Philip A. Briegleb and Walter H. Lund, Forest Management on the Quinault Reservation (Unpublished report commissioned by Bureau of Indian Affairs), 73. Inventory of the Quinault Indian Reservation Collection, 1939–1977, 3959, box 1, volume 1. Forest History Society Archives, Durham, NC.

[4] “People of the Quinault,” Quinault Indian Nation, 2003. http://www.quinaultindiannation.com/.

[5] Jacqueline Storm, “The Ancient Indian Fallers,” Quinault Natural Resources Vol. 13, no. 3 (Fall/Winter 1990): 16-17.

[6] Shale, Portrait of Our Land, 21.

[7] Shale, Portrait of Our Land, 7, 24.

[8] Shale, Portrait of Our Land, 8-9.

[10] Shale, Portrait of Our Land, 8-9.

[11] Shale, Portrait of Our Land, 8-9.

[12] “Present Status of Indian Treaties,” Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School, accessed March 11, 2021. https://www.law.cornell.edu/constitution-conan/article-2/section-2/clause-2/present-status-of-indian-treaties.

[13] Gregory Sisk, “Yesterday and Today: Of Indians, Breach of Trust, Money, and Sovereign Immunity.” Tula Law Review, Vol. 39 (2003-2004): 316. The Tucker Act grants jurisdiction to the Court of Claims over government contract money claims, and the Indian Tucker Act does essentially the same specifically for Indian tribal claims.

[14] “The Dawes Act,” National Park Service, accessed March 11, 2021. https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/dawes-act.htm#:~:text=The%20Dawes%20Act%20(sometimes%20called,to%20break%20up%20tribal%20lands.

[15] Shale, Portrait of Our Land, 9.

[16] Shale, Portrait of Our Land, 9.

[17] “The Dawes Act,” National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/dawes-act.htm#:~:text=The%20Dawes%20Act%20(sometimes%20called,to%20break%20up%20tribal%20lands.

[18] “The Logging History of the Quinault Reservation,” Quinault Natural Resources Vol. 7, no. 1 (Winter 1984): 5.

[19] Shale, Portrait of Our Land, 28.

[20] Robert E. Ficken, Elmo R. Richardson, Harold K. Steen, The Bureau of Indian Affairs and Forestry on the Quinault Indian Reservation: A History (Santa Cruz, CA: Forest History Society Inc. in cooperation with U.S. Dept. of Justice, 1977), 10.

[21] “The Logging History of the Quinault Reservation,” Quinault Natural Resources Vol. 7, no. 1 (Winter 1984): 5.

[22] Ficken, Richardson, and Steen, The Bureau of Indian Affairs and Forestry on the Quinault Indian Reservation, 10.

[23] Elwood R. Maunder, J. P. Kinney: The Office of Indian Affairs: A Career in Forestry (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1969), 8.

[24] “The Logging History of the Quinault Reservation,” 6.

[25] “The Logging History of the Quinault Reservation,” 10.

[26] Ficken, Richardson, and Steen, The Bureau of Indian Affairs and Forestry on the Quinault Indian Reservation, 53.

[26] Ibid, 31.

[27] “A Logging History of the Quinault Reservation–Part 2: The Thirties,” Quinault Natural Resources Vol. 7, no. 2 (March 1984): 4-5.

[28] Ibid.

[28] Ficken, Richardson, and Steen, The Bureau of Indian Affairs and Forestry on the Quinault Indian Reservation, 80.

[29] Shale, Portrait of Our Land, 10.

[30] Shale, Portrait of Our Land, 30.

[31] “A Logging History of the Quinault Reservation – Part 2: The Thirties,” 4-5.

[32] Ficken, Richardson, and Steen, The Bureau of Indian Affairs and Forestry on the Quinault Indian Reservation, 39.

[33] Ficken, Richardson, and Steen, The Bureau of Indian Affairs and Forestry on the Quinault Indian Reservation, 75.

[34] “A Logging History of the Quinault Reservation – Part 2: The Thirties,” 4-5.

[35] Dan Van Mechelen, “History of the Quinault Reservation,” http://www.vanmechelen.net/quinres.html.

[36] Shale, Portrait of Our Land, 32.

[37] Ficken, Richardson, and Steen, The Bureau of Indian Affairs and Forestry on the Quinault Indian Reservation, 71.

[38] Elmo Richardson, Forestry and the Federal Trust on the Quinault Indian Reservation: The Historical Context (Washington: Forest History Society for the U.S. Dept. of Justice and the Bureau of Indian Affairs, 1987), 13.

[39] Shale, Portrait of Our Land, 32.

[40] Richardson, Forestry and the Federal Trust on the Quinault Indian Reservation, 13-14.

[41] Richardson, Forestry and the Federal Trust on the Quinault Indian Reservation, 13-14.

[42] Ficken, Richardson, and Steen, The Bureau of Indian Affairs and Forestry on the Quinault Indian Reservation, 81.

[43] “A Logging History of the Quinault Reservation–Part 2: The Thirties,” 5.

[44] Richardson, Forestry and the Federal Trust on the Quinault Indian Reservation, 14.

[45] Ficken, Richardson, and Steen, The Bureau of Indian Affairs and Forestry on the Quinault Indian Reservation, 90-95.

[46] Ficken, Richardson, and Steen, The Bureau of Indian Affairs and Forestry on the Quinault Indian Reservation, 90-95.

[47] Ficken, Richardson, and Steen, The Bureau of Indian Affairs and Forestry on the Quinault Indian Reservation, 90-95.

[48] Ficken, Richardson, and Steen, The Bureau of Indian Affairs and Forestry on the Quinault Indian Reservation, 119.

[49] Shale, Portrait of Our Land, 35.

[50] Richardson, Forestry and the Federal Trust on the Quinault Indian Reservation, 23.

[51] Ficken, Richardson, and Steen, The Bureau of Indian Affairs and Forestry on the Quinault Indian Reservation, 128.

[52] “A Logging History of the Quinault Reservation – A Reprise,” Quinault Natural Resources Vol 8, no. 2 (Spring 1985): 14.

[53] “A Logging History of the Quinault Reservation – Part 3: The Forties and Fifties,” Quinault Natural Resources Vol. 7, no. 3 (Spring 1985): 6.

[54] Richardson, Forestry and the Federal Trust on the Quinault Indian Reservation, 31.

[55] Shale, Portrait of Our Land, 31.

[56] Ficken, Richardson, and Steen, The Bureau of Indian Affairs and Forestry on the Quinault Indian Reservation, 140.

[57] “Logging history of the Quinault Reservation – A Reprise,” 16.

[58] Mike O’Connell, “The Forest Damages Case,” Quinault Natural Resources Vol. 4, no. 5. (August-September 1983): 22.

[59] Ficken, Richardson, and Steen, The Bureau of Indian Affairs and Forestry on the Quinault Indian Reservation, 193.

[60] Richardson, Forestry and the Federal Trust on the Quinault Indian Reservation, 51.

[61] Ficken, Richardson, and Steen, The Bureau of Indian Affairs and Forestry on the Quinault Indian Reservation, 180.

[62] Ficken, Richardson, and Steen, The Bureau of Indian Affairs and Forestry on the Quinault Indian Reservation, 180.

[63] Richardson, Forestry and the Federal Trust on the Quinault Indian Reservation, 45.

[64] Ficken, Richardson, and Steen, The Bureau of Indian Affairs and Forestry on the Quinault Indian Reservation, 183.

[65] Richardson, Forestry and the Federal Trust on the Quinault Indian Reservation, 46.

[66] Sisk, “Yesterday and Today,” 318.

[67] Shale, Portrait of Our Land, 33.

[68] Richardson, Forestry and the Federal Trust on the Quinault Indian Reservation, 44.

[69] Richardson, Forestry and the Federal Trust on the Quinault Indian Reservation, 45.

[70] Richardson, Forestry and the Federal Trust on the Quinault Indian Reservation, 45.

[71] Ficken, Richardson, and Steen, The Bureau of Indian Affairs and Forestry on the Quinault Indian Reservation, 190.

[72] Richardson, Forestry and the Federal Trust on the Quinault Indian Reservation, 48.

[73] Ficken, Richardson, and Steen, The Bureau of Indian Affairs and Forestry on the Quinault Indian Reservation, 193.

[74] Sisk, “Yesterday and Today: Of Indians, Breach of Trust, Money, and Sovereign Immunity,” 318.

[75] Sisk, “Yesterday and Today: Of Indians, Breach of Trust, Money, and Sovereign Immunity,” 318.

[76] “United States, Petitioner v. Helen MITCHELL et al.,” Cornell Law School, accessed April 2, 2021. https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/445/535.

[77] Sisk, “Yesterday and Today: Of Indians, Breach of Trust, Money, and Sovereign Immunity,” 319.

[78] O’Connell, “The Forest Damages Case,” 22.

[79] Sisk, “Yesterday and Today: Of Indians, Breach of Trust, Money, and Sovereign Immunity,” 321.

[80] “Quinault Allottees annually provide the Nelson D. Terry Scholarship to Native American law students,” Law Admissions, Lewis and Clark Law School, March 13, 2017. https://law.lclark.edu/live/news/35689-quinault-allottees-annually-provide-the-nelson-d.

[81] “Quinault Allottees annually provide the Nelson D. Terry Scholarship.”

[82] Nell Jessup Newton, “The Re-Emergence of the Trust Relationship after United States v. Mitchell,” Land and Water Law Review, Vol. 18 (1983): 500.

[83] Lita P. Buttolph, William Kay, Susan Charnley, Cassandra Moseley, and Ellen M. Donoghue, Socioeconomic Monitoring of the Olympic National Forest and Three Local Communities (United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, and Pacific Northwest Research Station, 2006), ii.

Prepared in April 2021 by Jake MacDonnell, Library & Archives Intern and Master of Library Science 2021 at University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill, School of Information and Library Science. Assistance provided by FHS Staff and Gary Morishima of the Quinault Management Center.