Chinese Loggers in the American West

Tweet ShareThis exhibit was made possible with generous support from the MillsDavis Foundation and was curated by Shing Yin Khor. The project was overseen by FHS Librarian Lauren Bissonette, with help from FHS Historian James Lewis.

Introduction

In 1848, following the California Gold Rush, Chinese people quickly became part of American society. They established large Chinatowns on both American coasts and found employment in American industry, first in mining and railroads, and then in logging. The work was varied but always hard, and racial discrimination often made daily life that much harder. Despite the widespread Chinese presence in logging camps throughout the Sierra Nevada, the history and context of Chinese forest workers in the American West has only been documented by a few scholars, including Sue Fawn Chung and Yenyen Chen. This exhibit highlights the struggles and contributions of these Chinese workers.

Contents

Chinese Immigration to America

Life in the Woods

Racial Violence Against the Chinese

Chinese Workers in Popular Culture

Bibliography

Chinese Immigration to America

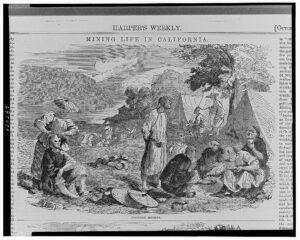

Chinese workers in Gold Rush diggings, 1857. (Mining life in California–Chinese miners. California, 1857. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2001700332/.)

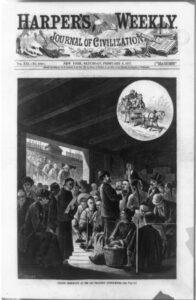

Chinese immigrants at the San Francisco custom-house / P. Frenzeny. San Francisco California, 1877. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/93510092/.

Initially, the United States saw very little immigration from China because of the combined effects of Chinese emigration policies and U.S. immigration laws. But China’s 1842 defeat in the First Opium War, growing economic and ecological problems in southeastern China, and the 1848 discovery of gold in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada of California changed that. The California Gold Rush attracted people not just from around the United States but from around the world. By 1852, California had at least twenty thousand Chinese, most of them male laborers.

Construction of the transcontinental railroad in the 1860s drew more Chinese immigrants. According to the 1890 census, there were 72,472 Chinese people in California, more than ninety-six percent of whom were men. After passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882—a law that placed a ten-year ban on immigration of Chinese “laborers,” a term so broadly defined in the law that it effectively banned the majority of Chinese immigrants—the Chinese population in California would decline over the next four decades. Chinese men found work mining gold, but in the largely bachelor society of the Gold Rush, they also found steadier income by doing more “feminine”-coded labor in the gold camps, such as cooking and laundry.

After a difficult trip just getting from China to the United States, a Chinese immigrant’s first stop would likely be a Chinatown. San Francisco’s Chinatown, the oldest in the country (and the second largest today, after New York’s), was the major port of entry for Chinese immigrants on the West Coast. Other Chinatowns prospered in Carson City, Nevada, and Truckee, California, which became the second largest on the West Coast after the transcontinental railroad was completed. Truckee Chinatown’s proximity to the Sierra Nevada made it central to logging concerns in the area, and was a hub for Chinese forest laborers.

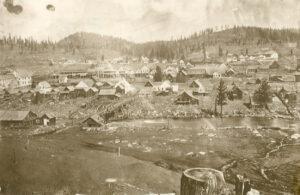

Shows Truckee River, rickety foot bridge, first Schaffer sawmill, trees denuded, Truckee Hotel, facing north. Also shows Chinese Herb Shop with laundry hanging outside. Circa late 1870s or late 1880s. Image Courtesy of the Truckee-Donner Historical Society.

In a Chinatown, immigrants found networks of mutual support in associations based on Chinese regional districts, dialects, or shared family names. In exchange for an annual fee, members of these associations would receive help with things like employment, housing, loans, disputes, and funeral services. The associations provided aid for members who could not find work and ran boarding houses for workers who rotated between logging camps and Chinatown. They were also points of contact for mining and logging companies looking for laborers. In The Chinese Question, Mae Ngai documents the communication challenges that many immigrants encountered. Chinese interpreters often spoke only a grammatically simplified form of English. This pidgin English was generally sufficient to conduct business but lacked the nuances necessary to, for instance, properly represent Chinese defendants at trial.

Chinese laborer at Tunnel 8 on the Donner Lake Railroad, c. 1862–1869. https://exhibits.stanford.edu/rr/catalog/gv106fk5547.

Chinese immigrants also faced institutional barriers. The racially targeted Foreign Miners’ Tax Act of 1850 initially charged all non-U.S. citizens $20 a month for mining. After European miners complained, it was amended to exclude “free white persons.” Although it was repealed after a year, a new tax of $3 a month was imposed in 1852. In addition, the increasing industrialization of mining and the takeover of land by mining corporations pushed out the majority of independent miners. Western mining communities even started prohibiting the Chinese from working in their towns in 1859.

In response to those developments, many Chinese workers went where there was work—the forests of California. Mines and railroads needed tremendous amounts of timber. By the late 1850s, California’s logging industry was not only meeting domestic demand but exporting lumber to Hawaii, Australia, and the Pacific coast of Latin America. Production in California in 1868 was 319 million board feet; by 1899, it was 737 million board feet. The mining and railroad industries and the timber operations that supported them could not have been profitable without the Chinese immigrants who worked in the woods.

Life in the Woods

No first-hand documentation of Chinese workers by other working-class men is known. Most information about them comes from archaeological research, census records, business and legal documents, and written accounts from White people, who were generally middle class.

We do know that a Chinese laborer’s life in the woods was difficult. Woodcutters worked twelve-hour days; cooks worked even longer hours. Chinese workers generally lived separately from other workers in bunkhouses or dormitories, although a few lived in private cabins. Some teams of migrant workers lived in simple canvas tents.

In addition to targeted racial violence, Chinese workers were subject to the dangers faced by all forest workers: flooding, fires, lightning, the hazards of woods work—drowning, accidental mutilation, falling trees—and other potentially fatal calamities. Many Chinese workers were employed as water flume builders and, even more dangerous, flume herders—the men who kept the logs moving in the flumes, which could sometimes flow at forty miles per hour.

A few Chinese men owned lumberyards, like the Yuen Fook Lumber Yard in San Francisco. But like most immigrants to the United States at this time, the majority of Chinese were laborers. In Chinese in the Woods, Sue Fawn Chung documents the breadth of work done by Chinese laborers in forest industry. “The Chinese were responsive to any call for employments,” she writes, “and logging was a familiar occupation” because cutting timber for fuel and construction was “a common occupation in every South China village.” She provides plentiful evidence that Chinese workers were employed in skilled positions, such as woodcutters and loggers—jobs that some Whites said the Chinese were incapable of doing—as well as highly valued jobs, such as cooking.

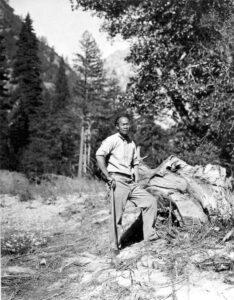

Yosemite National Park, California. Tie Sing, a 21-year veteran cook of the U.S. Geological Survey, in the field. 1909. https://www.sciencebase.gov/catalog/item/51ddc2f4e4b0f72b44720c63.

Chinese cooks could draw wages that equaled or even exceeded those of their American and European counterparts. They cooked Western meals for European and American loggers but traditional Chinese food for Chinese crews, using their networks of Chinese fishermen and farmers to procure fresh ingredients and supplies. In Chinese in the Woods, Chung tells of anti-Chinese mob resentment that led to the firing of Chinese cooks in the Puget Mill Company; the European and American cooks who replaced them proved incapable of meeting the demands of the job, which included baking one hundred pies daily in addition to making regular meals, and left within the week. The Chinese cooks were quickly rehired.

For American and European loggers, pay included board—hearty meals of steak and potatoes, bread, flapjacks, and dessert. But Chinese laborers often had to provide their own meals. Like Gold Rush miners, Chinese camp cooks provided for their countrymen, acquiring vegetables and fish from Chinese fishermen and part-time farmers.

Archaeological research has turned up woks in Chinese campsites, as well as Chinese imported goods (such as medicines and pottery) alongside many American goods, as miners adapted to the lack of familiar sundries by substituting more easily obtained alternatives. Often, common materials were modified into tools for Chinese cooking, such as tin cans punctured to serve as strainers. Traces of alcohol (Chinese whiskey or wine) and opium tins have been found; alcohol and opium were generally used for pain relief, not recreationally.

Mark Twain wrote about Chinese immigrants and their resourcefulness in his book Roughing It (1872):

What is rubbish to a Christian, a Chinaman carefully preserves and makes useful in one way or another. He gathers up all the old oyster and sardine cans that white people throw away, and procures marketable tin and solder from them by melting.

This was a largely bachelor society. In 1875, the Page Act, a law purportedly passed to prevent the immigration of “unfree” and “immoral” people, effectively prevented all Chinese women from entering the country. Chinese men in the American West were either unmarried or had left their families at home. Wives of upper-class merchants and businessmen were sometimes able to immigrate, though they often found themselves sequestered and isolated in their new homes. There were few working-class Chinese women in Chinatowns who were not sex workers, and in the more isolated logging camps, there were often no women of any race. Without the structure of family life, Chinese men who had been accustomed to strong familial and regional bonds endured a new loneliness.

Racial Violence Against the Chinese

Racial violence against all marginalized communities was endemic in the American West, and Chinese workers bore a significant amount of it. The same White supremacist laws that targeted Black people in the post-Reconstruction era generally included the Chinese and other non-White races as well. Racial discrimination was already virulent in American society, and Chinese immigration meant that Chinese workers would quickly become a new target for American racism.

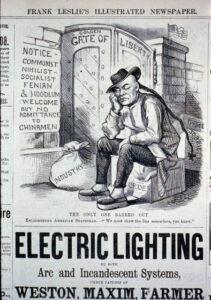

Page from magazine includes caricature commenting on the Chinese Exclusion Act showing a Chinese man seated outside Golden Gate of Liberty next to sign reading “Notice – communist, nihilist, socialist, Fenian & hoodlum welcome but no admittance to Chinamen” ; also on page are numerous advertisements for products such as bicycles, lighting, thread, face powder, and peas. (The only one barred out Enlightened American statesman – “We must draw the line somewhere, you know.”. United States, 1882. [New York: Frank Leslie] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2001696530/.)

The legislative attacks were mirrored in physical violence toward the Chinese, often led by organized anti-Chinese Leagues. The decade of the 1850s was marked by increasing violence toward Chinese people. In one of the most brutal incidents, known as the Trout Creek Outrage, White men who were part of the Caucasian League in Truckee, California, set two Chinese cabins on fire and attacked the Chinese woodcutters as they attempted to flee, killing one, wounding another, and terrorizing the community. The perpetrators went to trial, but despite eyewitness testimony from an English-speaking Chinese man, an all-White jury found the defendants not guilty.

The family and district associations in Chinatowns like Truckee’s were integral to helping Chinese people pursue justice through the legal system. Chinese workers won several court cases regarding unpaid wages, and they sued for the right to purchase property. Sometimes the courts sided with Chinese people in matters of business, but usually not in cases of violence and bodily injury. In 1854, the People v. Hall ruling on Section 394 of California’s Civil Practice Act, which barred the use of testimony by Black and Indigenous people against White people, extended to include Chinese people. Even when Chinese were allowed to testify, their testimony would be disregarded, as an oath sworn by a Chinese person on the Bible was considered meaningless.

In Roughing It, Mark Twain wrote about that aspect of injustice toward a Chinese person. His viewpoint is generalizing and presumptuous—attitudes evident even in pro-Chinese discourse of the time—but also sympathetic and generally complimentary.

He is a great convenience to everybody—even to the worst class of white men, for he bears the most of their sins, suffering fines for their petty thefts, imprisonment for their robberies, and death for their murders. Any white man can swear a Chinaman’s life away in the courts, but no Chinaman can testify against a white man. Ours is the “land of the free”—nobody denies that—nobody challenges it. (Maybe it is because we won’t let other people testify.)

When the economy declined in 1875 and competition for jobs intensified, anti-Chinese organizers made the Chinese labor force into scapegoats for job scarcity and lack of White working-class prosperity. Chinese immigrants were called “heathens” and “cheap labor,” even though Chinese workers were not known to have been paid significantly less than American or European workers. Nevertheless, the 1880 census for Carson City, Nevada, counted 295 Chinese people, including three merchants, two doctors, and eleven grocers.

As the eastern supply staging point for the construction of the Central Pacific Railroad’s transcontinental railroad, Truckee became the second-largest Chinatown in America, and its proximity to the Sierra Nevada also made it the most central Chinatown to logging concerns in California. In Ghosts of Gold Mountain, Gordon H. Chang notes that in 1870, thirty percent of Truckee’s population (407 people in a town of 1,467) and forty-five percent of the workforce in Truckee were Chinese. This was a prosperous and thriving Chinese population. In the 1868 and 1870 assessor’s records, approximately 35 Chinese property owners are listed. Large lumber companies actively recruited and employed Chinese men, who were generally considered reliable and hard working.

However, in 1878, anti-Chinese mobs burned Truckee’s Chinatown and prevented the Chinese from rebuilding it. Chinatown was forcibly relocated to the other side of the Truckee River, away from White-owned businesses.

Truckee then became the proving ground for one of the most virulent and intentional campaigns against the Chinese laborers, known as the “Truckee Method.” Led by Charles McGlashan, who represented the defendants of the Trout Creek Outrage at trial and was the owner of the Truckee Republican newspaper, anti-Chinese agitators demanded that Chinese leave Truckee by January 15, 1886. Boycotts were launched against any business that employed Chinese or traded or interacted with them. This was meant to be a “peaceful” way of removing Chinese laborers from Truckee, but in June 1886, a massive fire destroyed forty Chinatown buildings, and physical violence against Chinese workers continued to escalate. The November 1882 Truckee Republican printed a suggestion for “bloodless” physical assault: cutting off the queues, or long braids, of Chinese men:

To the people of California, and especially to anti-Chinese leagues, we suggest the bloodless remedy of cue [sic] cutting as an escape from serious complications, and a sure cure for the Chinese pestilence …

Charles McGlashan traveled around California, preaching the efficacy of the Truckee Method, with the anti-Chinese views of the day precisely reflected in an editorial in the Truckee Republican:

Let the China lovers get on their side of the line, so all may know them for what they are … teach the little ones to abhor a Chinaman or his upholder. Let the little fingers be pointed at them, and the first words that fall from their baby lips be, “Shame, you China lover.”

Not all employers of Chinese workers yielded to the mounting pressure. Several refused to break their contracts with Chinese employees and then faced vandalism and violence for their supportive stance. But by 1900, only two Chinese people were still living in Truckee. The numerous federal Chinese Exclusion Acts would not be repealed in full until 1943.

The passage of the first Chinese Exclusion Act, in 1882, essentially ended the flow of Chinese labor to the American West. The absence of Chinese women in America led to decreases in the overall Chinese population in the region. The logging industry was also changing. The need for labor slackened as timber companies in the 1910s began moving logs and lumber by truck instead of rail and water. The railroad and mining industries, once intertwined with the logging industry, were in decline. Deforestation and the rise of the forest conservation movement meant fewer jobs in the woods for everyone, not just the Chinese. Some workers returned to China, but many remained, shifting to other occupations and building their own lives in a new country.

Chinese Workers in Popular Culture

The past decade has seen a new focus on Chinese laborers in the American West. Kelly Reichardt’s 2019 movie, First Cow, explores the friendship between a White man and a Chinese immigrant trying to survive in the Oregon Territory. AMC’s historical fiction series about the construction of the transcontinental railroad, Hell on Wheels, at first ignores the involvement of Chinese workers by focusing on the eastbound Union Pacific but in its fifth and final season depicts the westbound Central Pacific Railroad and features a group of Chinese characters in Truckee. Among them: Tao, a crew foreman; his daughter Fong; and Chang, the primary labor contractor for all Chinese men working on the Central Pacific Railroad. The series examines racial tensions and resentments but is especially interesting for its portrayal of Chang as a complex and ambitious antagonist.

The past decade has seen a new focus on Chinese laborers in the American West. Kelly Reichardt’s 2019 movie, First Cow, explores the friendship between a White man and a Chinese immigrant trying to survive in the Oregon Territory. AMC’s historical fiction series about the construction of the transcontinental railroad, Hell on Wheels, at first ignores the involvement of Chinese workers by focusing on the eastbound Union Pacific but in its fifth and final season depicts the westbound Central Pacific Railroad and features a group of Chinese characters in Truckee. Among them: Tao, a crew foreman; his daughter Fong; and Chang, the primary labor contractor for all Chinese men working on the Central Pacific Railroad. The series examines racial tensions and resentments but is especially interesting for its portrayal of Chang as a complex and ambitious antagonist.

Prairie Lotus, a historical novel for middle schoolers by Linda Sue Park, is a book in conversation with the Little House on the Prairie series. A biracial Chinese American girl, Hanna, navigates living on the prairie with her widowed father and contends with the racial tensions of the day. My own work, The Legend of Auntie Po, a graphic historical novel for the middle grades, is built on research by Sue Fawn Chung and others on Chinese labor in logging camps. The 12-year-old protagonist, Mei, works in the kitchen with her father, the head cook, to feed a logging camp of White and Chinese workers in the Sierra Nevada, and tells reinvented Paul Bunyan stories. The book is inspired by historical records of racial tensions and violence but also the skill of Chinese cooks and the camaraderie and alliances of the working class.

The story of Chinese labor in the early American West, especially as it relates to the forest industry, is not well recorded or appreciated. The thorough work done by researchers and archaeologists has yet to enter mainstream cultural discussions and histories of the West. Despite anti-Chinese racism and mistreatment, thousands of Chinese workers were essential in the American West: building the transcontinental railroad, mining gold and silver, and especially, logging the forests.

Bibliography

Aarim-Heriot, Najia. Chinese Immigrants, African Americans, and Racial Anxiety in the United States, 1848–82. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2003.

Albright, Horace Marden, Marian Albright Schenck, and William C. Tweed. The Mather Mountain Party of 1915 and the Founding of the National Park Service. Three Rivers, CA: Sequoia Natural History Association, 2014.

Chang, Gordon H. Ghosts of Gold Mountain. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2019.

Chang, Iris. The Chinese in America. New York: Viking, 2003.

Chung, Sue Fawn. Chinese in the Woods. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2015.

Furnis, Lynn, and Mary L. Maniery. “An Archaeological Strategy for Chinese Workers’ Camps in the West: Method and Case Study.” Historical Archaeology 49, no. 1 (2015): 71–84.

Heffner, Sarah. Archaeological Investigations of 委李架埠 Yreka’s Chinese Community. Publications in Cultural Heritage, No. 36. Sacramento: California Department of Parks and Recreation, 2019.

Ngai, Mae. The Chinese Question: The Gold Rushes, Chinese Migration, and Global Politics. Washington, DC: National Geographic Books, 2022.

Powell, Mary. “Shooting the Fastest Chute in the World.” San Francisco Call. September 10, 1911.

“A Glimpse into Yosemite’s Chinese History.” YouTube, uploaded by yosemitenationalpark, 22 December 2011.