The Bureau of Land Management at Seventy-Five: Who Will Celebrate with Them?

In 2021, the Bureau of Land Management turned 75 but with little if any fanfare. Historian James R. Skillen, who's written extensively about the BLM, reflected upon its history. This article appears in the 2021 issue of Forest History Today.

July 16, 2021, was the Bureau of Land Management’s seventy-fifth anniversary, but celebration was probably muted at the agency’s relatively new headquarters in Grand Junction, Colorado. The Trump administration came into office in 2017 promising to deconstruct the administrative state,1 and BLM felt the hostility of that promise for the next four years. The administration never appointed a permanent director, and BLM’s acting director, William Perry Pendley, was one of its most vocal critics.2 Most significantly, the administration moved the BLM headquarters to Grand Junction in 2019 and scattered many senior staff to various state offices around the West. The move had the intended effect of gutting BLM’s senior career staff, with roughly eighty percent of headquarters staff resigning or retiring.3 And as perfect bookends, the Republican Party’s 2016 and 2020 platforms included a pledge to transfer public lands to the states.4

The Biden administration has been more supportive of public lands and BLM but is still challenging a long-standing priority and source of revenue generation for the agency: fossil fuel development. Meanwhile, Interior Secretary Deb Haaland decided to move the BLM headquarters back to Washington, and the new director, Tracy Stone-Manning, is working to accomplish that while simultaneously refilling a host of vacant positions.5

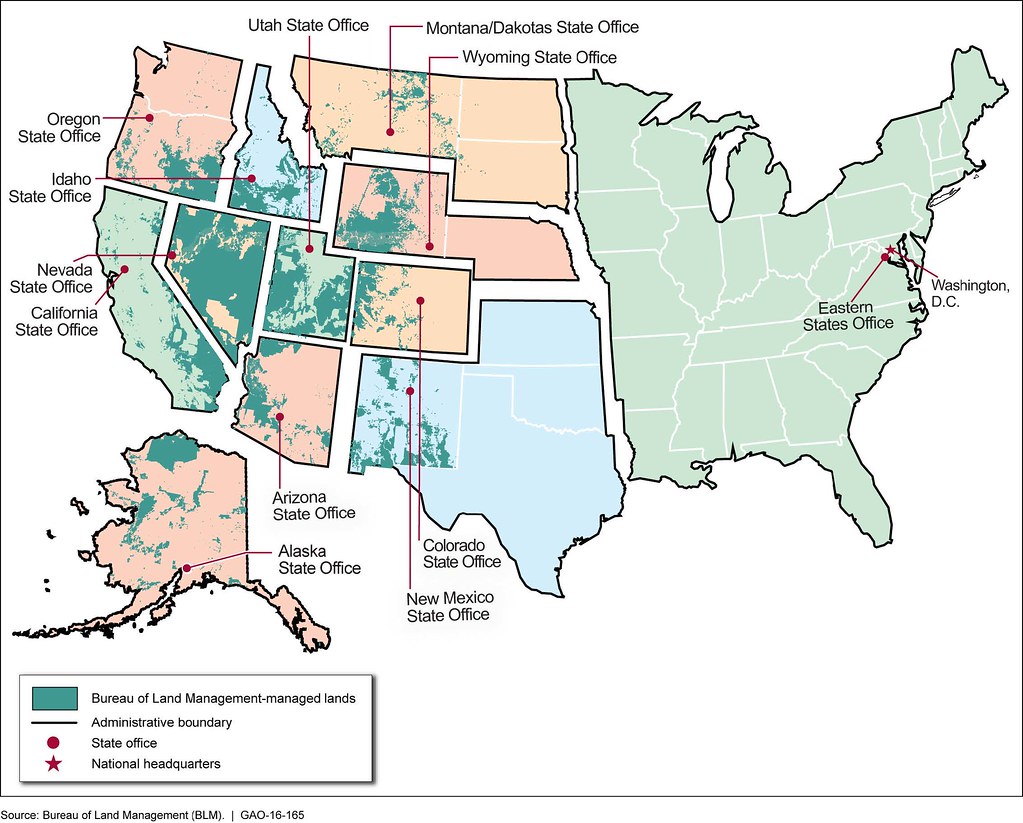

This map showing how the BLM divides the country into different regions for management purposes can, to a degree, represent the divided opinions held by various stakeholders, agency officials, and even political parties over the purpose and management objectives of the agency, particularly the east-west divide.

Although the past few years have been particularly challenging for the agency, they haven’t been unique. Rather, BLM’s seventy-fifth year encapsulates well the achievements and challenges of multiple-use public lands management. Whereas the national parks, national forests, and national wildlife refuges were all set aside for particular purposes, and previous land-use practices and claims were generally eliminated in the process, the public lands managed by BLM have a long history of conflicting land-use claims made by western states, miners, livestock operators, and many others. Most shifts in public lands management have been incremental, and they been more often administrative than legislative.

Perhaps it is this longer history that has made it difficult for BLM to celebrate its milestone anniversary more visibly and with greater fanfare. After all, what would it celebrate? Its greatest accomplishments, in many ways, have been in mediating conflicting public demands. Celebrating those negotiations would only remind public land users that they have not gotten everything they want. And who will celebrate with BLM? The agency does not have a primary, supportive constituency, and until this year, it did not have a nonprofit counterpart, as the U.S. Forest Service does in the National Forest Foundation. The national political climate is so polarized and toxic that some BLM employees, who are “often the most visible and vulnerable representatives of the federal government in remote areas and have been subject to a range of threats and assaults,” would feel unsafe drawing attention to themselves and their work.6

BLM’s seventy-fifth anniversary deserves far more attention than it has received, both to evaluate the past and to consider the agency’s outsized importance in the coming decades. To start with, BLM manages roughly ten percent of all surface land in the United States, concentrated in the eleven western states and Alaska. The history of these lands is important ecologically, and it is central to the economic and cultural story of the American West. Perhaps most troubling, the challenges of the past forty years reflect the growing partisanship and antigovernmentalism that now threaten our democratic institutions. For these reasons and others, we should attend to and learn from BLM’s past.

But the agency’s anniversary also deserves more attention because BLM now sits at the crossroads of one of the most important national questions of our time—namely, whether the United States will decarbonize its energy economy. BLM oversees some seven hundred million acres of on-shore subsurface minerals owned by the federal government. Its leasing of these minerals is a limiting factor in the total volume of coal, oil, and gas that support our economy, and its leasing and patenting of hard rock minerals are critical to the production of the technologies needed for alternative energy sources to work. So BLM is not only the nation’s largest land manager by area, it is also the largest supplier of fossil fuels and hard rock minerals in the country.

BLM’s history, like that of the U.S. Forest Service, is a story of an expanding mission. In BLM’s case, the agency’s early mandate came almost entirely from land and resource disposal laws. Because of this, for many years it was nicknamed the “Bureau of Livestock and Mines.” The agency’s early accomplishments were primarily bringing greater order and federal oversight to resource development on the public lands. But over time, the agency’s mission expanded to include activities such as outdoor recreation, endangered species protection, and national monument management—new responsibilities that added to, rather than supplanted, the agency’s resource development objectives. This is, as historian Paul Hirt once wrote of the Forest Service, the “conspiracy of optimism” inherent in multiple-use management: the idea that an agency can meet more and more diverse public demands without a fundamental revision to its mandate.7 The debate over decarbonizing the U.S. energy economy for the first time suggests that BLM might, at some point in the future, drop a central element of its current multiple-use management mission.

To understand the past and the present questions that BLM, Congress, and the American people face, it is helpful to think about other significant moments in the agency’s history and the context and contingencies that nudged the agency in new directions. Any effort to do this in a few pages is necessarily a thin outline, which is organized here around eight inflection points.8

1. Formation, 1946

BLM arose from a merger of the General Land Office and the U.S. Grazing Service. If the goal was creating a national system of public lands or a professional land management agency, it was not an auspicious start. Consider the BLM’s origins. When the General Land Office was established in 1812, its primary task was to transfer public domain lands, which in 1946 totaled more than five hundred million acres, into state and private ownership and to get public domain resources into the market economy. For all intents and purposes, it had been a real estate agent.

In contrast, during its eleven-year existence, the U.S. Grazing Service had a management mandate, but there was no clear consensus on what that meant. The service’s director in 1946, Clarence Forsling, had come from the Forest Service and was trying to build professional management capacity on that blueprint. Public lands ranchers generally saw the Grazing Service as an agency to help with their rangeland, something more akin to the modern Natural Resources Conservation Service.

That tension came to a head in Congress in 1946. Appropriations committees in both the House and the Senate demanded that range management become self-sustaining, but they diverged sharply from there. One committee demanded higher grazing fees to cover the cost of professional range management; the other committee demanded lower grazing fees and a commensurate reduction in management capacity, which would effectively maintain what the first grazing director had called “Home Rule on the Range.” When they couldn’t agree on grazing fees, they simply slashed the Grazing Service’s budget, ultimately cutting its staff by eighty percent at the very moment of the BLM’s formation. It would be more accurate to say that BLM was created by merging the General Land Office with a remnant of the U.S. Grazing Service.

The grazing controversy illustrates an important source of tension that continues today. When public lands ranchers agreed to organized grazing districts, they tended to see the arrangement as a service that protected their interest in the public lands. Regulation and active management that limited livestock grazing infringed on what ranchers considered to be their superior claims to the public lands, and being told to pay higher grazing fees was essentially being asked to fund an injustice. This same tension exists in other areas of BLM’s multiple-use management as well.

Over the next fifteen years, BLM rebuilt and expanded its budget and staff, building a more coherent administrative organization. The problem was that it wasn’t organizing around a coherent mandate or mission. Its work was still directed by what one Interior official described as “the crazyquilt patchwork of public land laws, altered and mended and embroidered to meet the exigencies of the moment, [and which did not] add up to a national land policy and program.”9 To be clear, this wasn’t a gap between congressional goals and BLM experience; rather, Congress had no national land policy and program in mind.

BLM’s first emblem, unveiled in 1954, captured the agency’s mission and purpose. From top to bottom are a land surveyor, a lumberjack or logger, an oil derrick worker, a rancher, and a miner, with oil wells and other industrial infrastructure on the right side, and Conestoga wagons, representing the heritage of land disposal, on the left. If anything, the emblem simply illustrated the moniker Bureau of Livestock and Mining.

2. Multiple-Use Management, 1964

People generally refer to the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976 as the agency’s “organic act” when talking about BLM’s multiple-use mission. But FLPMA did not initiate multiple-use management in BLM, nor was it even the agency’s first multiple-use mandate. It simply affirmed and permanently codified what the agency was already doing. The year 1964 is a more important inflection point for the origins of multiple-use management at BLM.

Two forces came together in the 1960s that reshaped federal land management more broadly, placing growing pressure on BLM and Congress to develop a more comprehensive approach to public land management. The first was outdoor recreation. After World War II, Americans increasingly had leisure time and disposable income, and outdoor recreation surged. The 1950s saw a steady flow of reports and articles with titles like “The Crisis in Outdoor Recreation”—a number of which were written by a former BLM director, Marion Clawson.10 Congress established the Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission in 1958 to address the “crisis,” and Congress funded initiatives in the national parks and forests to dramatically expand outdoor recreation infrastructure.

BLM remained in a curious position. Outdoor recreation was certainly expanding on the public lands, but the agency was still approaching such pursuits as a land disposal, rather than management, issue. Its primary authority was to sell or lease public lands for outdoor recreation. Congress codified BLM’s peripheral recreation status in the Wilderness Act of 1964 by not including BLM public lands. What is more, the agency’s public lands did not appear on most national atlases, so they were largely invisible to Americans traveling across the country to visit parks, forests, and wildlife refuges. But as Americans flocked to the public lands, Congress and BLM had to decide how recreation fit into the agency’s mission.

The second force was a growing ecological consciousness in America. An increasing number of Americans were coming to see the environment not simply as a collection of resources but as an integrated web of relationships, and this vision demanded a more comprehensive approach to management. There was no greater champion of this vision in the 1960s than Interior Secretary Stewart Udall, whose department oversaw BLM.

Those forces led to congressional action. Congress established the Public Land Law Review Commission in 1964 to consider federal land and resource law in its entirety and recommend improvements. Its 1970 report, One Third of the Nation’s Land, was critical in shaping FLPMA in 1976. But of more immediate importance, Congress in 1964 passed the Classification and Multiple-Use Act as well, giving BLM temporary authority to classify public lands for disposal under existing law or for retention and multiple-use management. Interior and BLM leaders capitalized on this authority and worked to remake the agency on the Forest Service model of multiple-use conservation, placing resource development programs like range management and timber in a larger conservation context. This was reflected in BLM’s next emblem, unveiled in 1964 and still used today. The absence of any signs of development or industry, or even human presence, stands in stark contrast to its predecessor. In a way, it is an aspirational vision of what Secretary Udall had talked about.

3. The Environmental Turn, 1970

The 1970s are often called as the environmental decade. Almost every major federal environmental statute constituting our national environmental policy was passed or amended between 1969 and 1980, responding to a public call for comprehensive and coherent environmental protection. BLM began to build a more expansive multiple-use management mission in the 1960s, but 1970 was a pivot point in the shift toward more ecologically oriented multiple-use management.

In the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969, Congress declared a national policy to “encourage the productive and enjoyable harmony between man and his environment.” When he signed NEPA into law on January 1, 1970, President Nixon said, “The nineteen-seventies absolutely must be the years when America pays its debts to the past by reclaiming the purity of its air, its waters, and our living environment.”11 This goal met the public demand for a comprehensive policy of environmental protection. More importantly, it reflected an ecological reframing of multiple-use management. The real power of NEPA wasn’t in its lofty statement of purpose but in its procedural requirements that agencies prepare an environmental impact statement for each “major federal action with significant impacts on the environment” and that citizens have opportunity to enforce this process through the courts.

NEPA had three significant effects on BLM: its public participation requirements opened the agency’s decision making in new ways to all Americans; it exposed the agency to extensive new litigation; and most importantly, it led BLM to hire more diverse staffers with social science expertise, known collectively as “ologists”: ecologists, sociologists, economists, and biologists, to name a few. NEPA thereby altered the BLM’s workforce and culture.

One Third of the Nation’s Land also recommended a more coherent framework for BLM’s public lands. Over the next ten years, Congress passed a shower of legislation that affirmed and expanded the agency’s multiple-use management and environmental responsibilities. The Endangered Species Act of 1973, for example, prohibits federal agencies from taking any action that would jeopardize a listed threatened or endangered species. Like many statutes over the years, ESA simply added a new responsibility to BLM’s already full plate, producing both intended and unintended consequences. But ESA did not help BLM refine multiple-use management.

4. Reshaping Multiple-Use Management and Politics, 1976

With passage of the Federal Land Policy and Management Act in 1976, Congress finally gave BLM a permanent multiple-use mandate. The basic framing was identical to the National Forest Management of 1976, passed for the Forest Service as its new organic act. In FLPMA, Congress finally declared what most people already expected—that public lands would remain in permanent federal ownership—and Congress therefore repealed a wide range of land disposal statutes.

FLPMA made BLM’s mission both more coherent and more complex. On the one hand, it provided a set of overarching goals and values for balancing multiple uses. Furthermore, it created a new, comprehensive land-use planning process modeled after, and later integrated with, the preparation of environmental impact statements. The new process ensured a multidisciplinary approach to planning for all resource management programs and opened decision making to extensive public participation and review. The process thus accelerated the changes that NEPA initiated in the early 1970s, solidifying BLM’s expansive multiple-use mission as defined by FLPMA: that the public lands be managed in a manner that will protect the quality of scientific, scenic, historical, ecological, environmental, air and atmospheric, water resource, and archeological values; that, where appropriate, will preserve and protect certain public lands in their natural condition; that will provide food and habitat for fish and wildlife and domestic animals; and that will provide for outdoor recreation and human occupancy and use.12

On the other hand, FLPMA added new authorities and responsibilities that have made BLM’s work more controversial. Two examples will suffice. First, the act gave BLM comprehensive law enforcement authority, although it also directed the agency to achieve “maximum feasible reliance” on contracts with local law enforcement. The new law enforcement program that followed, albeit with very limited staffing, was a visible reminder to western states and counties that these were federal lands under federal authority, not federally owned lands under local authority. And tension between federal and local law enforcement has been a recurring issue in Congress and in many parts of the West. Second, FLPMA extended the Wilderness Act to BLM, directing the agency to review its lands for wilderness characteristics and to make recommendations by 1991. The agency finished its review of the lower forty-eight states by 1980, establishing 919 wilderness study areas totaling more than twenty-three million acres. Wilderness review and designation have been contentious developments, particularly for an agency that historically had emphasized economic resource development.

Nevertheless, in the midst of the 1970s oil crisis, the BLM remained firmly committed to energy development and continued to support other kinds of economic development on public lands.

5. The Sagebrush Rebellion, 1979

FLPMA may have given BLM a new, comprehensive mandate, but it didn’t create any new, unified support for the agency. Indeed, FLPMA’s passage and implementation under the Carter administration sparked a wave of protest in the West called the Sagebrush Rebellion. It was led by both Democrats and Republicans who had a material interest in the public lands and who waged it primarily through state legislative action that claimed ownership of federal public lands. Constitutionally, the rebellion was a states’ rights challenge grounded in the Tenth Amendment. The rebellion continued for three years, finally fizzling out when Ronald Reagan’s Interior secretary, James Watt, told western governors to take what they wanted from the public lands. The Sagebrush Rebellion was a inflection point not so much in BLM as in the broader politics of public lands.

Reagan won a landslide election in 1980 in part because he brilliantly harnessed wide-ranging frustration with the federal government’s growing role in areas like civil rights, gender equality, environmental protection, and workplace safety. Reagan had campaigned on a promise to get government off our backs: “Government is not the solution to our problem,” he said, “government is the problem.”13 FLPMA had given the BLM new authority, but it was now caught in a national, partisan debate over the legitimacy of federal authority in many areas of society.

6. Ecological Management, 1992

When Vice President George H. W. Bush ran for president in 1988, he pledged to be “the environmental president.” Like other conservative environmentalists, President Bush supported environmental protection but attacked federal regulation as overbearing. He had promised that environmental protection and economic growth were not mutually exclusive and that under his leadership, both could flourish. This both-and approach was good for BLM, given its multiple-use mandate, but the agency stumbled in a very public way in the Pacific Northwest when the northern spotted owl and ESA essentially shut down logging on federal lands. By the time Bush ran for reelection in 1992, he had shed his environmental president claim, instead condemning ESA as a sword that destroyed American families.

On succeeding Bush in 1993, President Bill Clinton promised to resolve the spotted owl crisis, and the BLM and Forest Service worked with other federal agencies on a comprehensive ecosystem management plan for all federal land in the spotted owl’s habitat. Given the requirements of the ESA, the compromise plan hardly met environmentalists and industry in the middle. Essentially, it established stringent protections for the owl and other vulnerable species and produced only a trickle of timber from the more than 2.4 million acres of forests known as BLM’s O&C land in Oregon.14

The Bush administration had inaugurated a decade of new conflict over the public lands. BLM embraced ecosystem management and developed new capacities to manage large ecological systems. It placed greater emphasis on ecological priorities, such as riparian area health in range management. The Clinton administration put many areas of public lands on the map, quite literally, by creating national monuments across the West, which were then incorporated into the National Landscape Conservation System. All these changes were met with a new wave of conservative rebellion often referred to as the War for the West. Unlike the Sagebrush Rebellion a decade earlier, this rebellion was waged almost exclusively by Republicans. And this time, western Republicans had a national, conservative infrastructure of think tanks, foundations, and political advocacy organizations that gave them allies across the country.

The War for the West was really a national struggle over the scope and purpose of the federal government, which in the West naturally entailed federal lands. States’ rights remained important, but this time, the national conservative rebellion integrated frustrations over property rights, gun rights, and religious expression rights as well. And in addition to state action, this rebellion was advanced by the County Supremacy Movement—conspiracy-driven militias, politically ascendant gun rights groups, and others that challenged federal authority—making it both a more expansive and a more dangerous rebellion. Though BLM employees had always dealt with threats and intimidation in the course of their work, there is good evidence that threats and risks increased substantially during this period.

7. A New Partisan Challenges, 2009

The next inflection point for the bureau arrived not because the agency changed fundamentally but because it entered a new, and more dangerous, chapter of partisan confusion. In 2009, Congress passed the Omnibus Public Land Management Act, which among other things created new BLM wilderness areas and codified them in the National Landscape Conservation System. The act passed with strong bipartisan support, reflecting the persistent bipartisan interest in outdoor recreation. But 2009 also marked the birth of the Tea Party and its armed wing, the Patriot Movement. The general goal of the Tea Party was pruning government back to its eighteenth-century roots. What is more, it was a populist rebellion, and its members argued that they, rather than the courts, had ultimate say over what the Constitution meant. Over the next decade, the extreme conservative positions and actions of the Tea Party and Patriot Movement became mainstream in the Republican Party.

Right-leaning ideology has increased hostility toward federal agencies, including BLM, and has reignited efforts to dispose of the public lands despite widespread popular opposition. It has produced an even more expansive and public militia movement. These, in turn, contributed to the 2014 standoff in Bunkerville, Nevada, between federal law enforcement officers and supporters of the Bundy family, and to other armed standoffs in Oregon and Montana. In each case, Oath Keepers, Three Percenters, and other militia groups mobilized quickly to thwart federal enforcement of basic land laws. The threat has been compounded by the rise of groups like the Constitutional Sheriffs and Peace Officers Association, whose members assert that as elected county sheriffs, they can nullify any federal or state laws with which they disagree. And it has been compounded by members of Congress who continue to press for BLM to eliminate law enforcement officers or at least disarm its agents.

8. Too Early to Title, 2020

BLM is likely at another inflection point. Riding a wave of populist antigovernmentalism, which had grown out of the Tea Party and Patriot Movement, Donald Trump vowed to dismantle the executive agencies. His administration routinely condemned civil servants and promoted conspiracies about a “deep state” that plotted against liberty, and it left agency posts empty or filled them with people in an acting capacity. And Trump’s pardons for Oregon ranchers Dwight and Steven Hammond and Maricopa County (Arizona) Sheriff Joe Arpaio signaled that the administration would not support BLM’s full legal authority. This created a demoralizing environment in which to work.

Yet 2020 was also a positive inflection point: Congress passed the Great American Outdoors Act with bipartisan support, and Covid, though deadly, swelled the ranks of outdoor recreationists. After all, if you want social distancing, the public lands are an ideal destination. In the midst of deeply polarized politics and public attacks, it is reassuring to see that Americans support at least some aspect of public lands management, and this is confirmed in poll after poll. Indeed, a majority of Americans even support the Biden administration’s pledge to protect thirty percent of American lands and waters by 2030 under its so-called 30 x 30 Plan,15 and with ten percent of the nation’s land under its purview, BLM will play a critical role.

But the biggest change for BLM is energy development. Although Biden’s temporary moratorium on new oil, gas, and coal leasing was struck down by the courts, a permanent moratorium remains a possibility, portending an uncertain future for BLM’s largest program, by revenue. Debate over federal energy development will likely dominate public lands politics for the next several administrations and congresses, but the Biden administration is already planning to reduce the cost of solar development on the public lands. Imagine BLM and its public lands with extensive solar and wind farms and no oil, gas, or coal development.

The Next Seventy-Five Years

The Bureau of Land Management has for seventy-five years been responding to changes in public land politics and the western economy. As its 1954 emblem suggests, it focused initially on the orderly disposal of federal land and resources, but over time, it gained new and diverse responsibilities for goals like wilderness preservation and endangered species protection. Its mission has become more comprehensive and more complex, and the current level of bitter partisanship in American politics offers little hope that the agency will be able to resolve the tensions inherent in that mission. The demands that Americans make on the public lands will continue to shift.

Several issues may provide early signals about upcoming changes. The first is simply the state of American democracy. For much of BLM’s history, its managers have found some success in working with communities on compromises in its multiple-use management. But the current partisan vitriol, facilitated by fissiparous media, national interest groups, and large corporations, leaves little space for BLM managers and community members to find common ground. And the problem isn’t simply ideological conflict. A growing percentage of Americans seem to accept that violence may be necessary to achieve their political goals, making it all but impossible to build a sense of safety and trust in public land negotiations.16 Unless these dynamics change, it is very difficult to see how the agency will reduce conflict over the lands it manages.

A second issue is climate change. At the very least, decarbonizing the economy requires reducing fossil fuel development and increasing renewable energy sources like solar, wind, and hydropower. The United States has made progress in reducing carbon emissions primarily by switching from coal to natural gas in the power sector. If the nation can find bipartisan will to go further, the next step is changing land-use priorities. Phasing out the leasing and permitting of federal oil, gas, and coal deposits and permitting solar and wind development on public lands would dramatically alter the agency’s budget and the balance of multiple-use management. Such a shift away from carbon-based energy seems likely, but how quickly will it happen and how will it affect the agency and western communities?

The final issue to watch is the role of BLM’s new nonprofit entity, the Foundation for America’s Public Lands. Congress approved the foundation in 2017 and it was officially launched in January 2022.17 Modeled after similar foundations that support the National Park Service, the U.S. Forest Service, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the new foundation can create partnerships and raise funds in ways that federal agencies cannot. For better and for worse, this creates an entirely new arena in which Americans can influence the direction of public land management by BLM. If this foundation, like the other three, builds stronger conservation support for public land management from environmentalists, hunters, anglers, and local communities, how might this shift the agency’s priorities?

Managing ten percent of the nation’s land, the agency will always be caught between competing visions for land and resource management. It’s safe to predict only that it will continue to face controversy and undergo shifts in its administrative priorities as Republicans and Democrats trade places in the White House.

James R. Skillen is Associate Professor of Environmental Studies, and Director of Calvin Ecosystem Preserve and Native Gardens, at Calvin University in Grand Rapids, Michigan. He is the author of The Nation’s Largest Landlord: The Bureau of Land Management in the American West (2009). His most recent book is This Land Is My Land: Rebellion in the West (2020).

NOTES

1 Max Fisher, “Stephen K. Bannon’s CPAC Comments, Annotated and Explained,” New York Times, Feb. 24, 2017.

2 Lisa Friedman and Claire O’Neill, “Who Controls Trump’s Environmental Policy?,” New York Times, Jan. 24, 2020.

3 The agency itself reported “more than 80 percent of the employees in affected positions did not relocate.” See: Bureau of Land Management, “BLM FY 2022 Budget in Brief” (Washington, DC: Bureau of Land Management 2021), BH-12, at https://www.doi.gov/sites/doi.gov/files/fy2022-bib-bh007.pdf. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland said nearly 90 percent of headquarters staff retired, quit, or left for other jobs. Joshua Parlow, “Bureau of Land Management Headquarters to Return to D.C., Reversing Trump Decision,” Washington Post, Sept. 17, 2021.

4 “Republican Platform 2016,” (Washington: Republican National Committee, 2016). In 2020, the party leadership adopted the 2016 platform without changes. “Preamble,” https://prod-static.gop.com/media/Resolution_Platform_2020.pdf.

5 Lisa Friedman, “The Bureau of Land Management Is Moving Back to Washington,” New York Times, September, 17, 2021.

6 “Federal Land Management Agencies: Additional Actions Needed to Address Facility Security Assessment Requirements,” (Washington, DC: Government Accountability Office, 2019), https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-19-643.

7 Paul Hirt, A Conspiracy of Optimism: Management of the National Forests since World War Two (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1994).

8 I have kept notes sparse for space. Unless otherwise cited, the information in this essay comes from my publications: The Nation’s Largest Landlord: The Bureau of Land Management in the American West (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2009), and This Land Is My Land: Rebellion in the West (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020).

9 Quote in Skillen, Nation’s Largest Landlord, 50.

10 For example, Marion Clawson, “The Crisis in Outdoor Recreation,” American Forests 65, no. 3 (1959), 22–31, 40–41; and “The Crisis in Outdoor Recreation, Part II,” American Forests 65, no. 4 (1959), 28–35, 61–62.

11 Skillen, Nation’s Largest Landlord, 89.

12 U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management, ed., The Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976, As Amended (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management, Office of Public Affairs), 1, available at: https://www.blm.gov/sites/blm.gov/files/documents/files/FLPMA2016.pdf.

13 Inaugural Address, January 20, 1981, The Public Papers of President Ronald Reagan, Ronald Reagan Presidential Library, https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/ research/ speeches/ inaugural-address-january-20-1981.

14 Oregon and California Railroad Revested Lands, known as the O&C lands, lie in a checkerboard pattern through eighteen counties of western Oregon. These lands are a large part of the critical habitat of the northern spotted owl.

15 See, for example, Lori Weigel and Dave Metz, “2021 Survey of the Attitudes of Voters in Eight Western States,” Colorado College State of the Rockies Project (Colorado Springs, 2021); Morning Consult, National Tracking Poll #210541 (Washington, DC, 2021).

16 Aaron Blake, “Nearly 4 in 10 Who Say Election Was Stolen from Trump Say Violence Might Be Needed to Save America,” Washington Post, November 1, 2021.

17 U.S. Department of the Interior, “Interior Department Announces Historic Launch of the Foundation for America’s Public Lands,” Press Release, January 19, 2022, https://www.doi.gov/pressreleases/interior-department-announces-historic-launch-foundation-americas-public-lands.