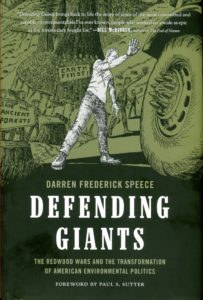

A Clear-eyed History of the Redwood Wars: A Review of the Book “Defending Giants”

FHS historian James Lewis wrote this review of Defending Giants: The Redwood Wars and the Transformation of American Environmental Politics, by Darren Frederick Speece (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2016) for Western Historical Quarterly. It was published in the October 2017 issue.

FHS historian James Lewis wrote this review of Defending Giants: The Redwood Wars and the Transformation of American Environmental Politics, by Darren Frederick Speece (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2016) for Western Historical Quarterly. It was published in the October 2017 issue.

The tallest species in the world, the redwood tree (sequoia sempervirens) is found in a narrow range in northern California. In the late 1800s redwoods attracted lumbermen for their resistance to rot and fire and preservationists for their majestic groves and awe-inspiring appearance. At more than 350 feet tall, their height had been such an obstacle to studying the crowns that it was not until the late twentieth century that ecologists and other scientists climbed into the canopy and discovered a separate ecosystem far more complex than previously known. They found trunks growing out of the main trunk, and then trunks off of those trunks, all intertwining to form a loose web that enable other plants and rare fauna to thrive.

That researchers knew so little about this species until recently is analogous to what environmental historians understood about the late-twentieth-century fights, known as the Redwood Wars, to preserve them. The wars began in 1955, when a Pacific Lumber Company clearcut caused downstream flooding that triggered soil erosion problems and toppled thousand-year-old redwoods. The incident also opened a schism in the conservation movement. Until then, the accepted process for preserving tracts of redwoods had worked thusly: the Save the Redwoods League would appeal to the State of California and badger Pacific Lumber to protect tracts containing exceptional specimens; the company would protest a bit; and then the league would use private funds to purchase the land, which then became a state park. After the 1955 floods, though, this arrangement starting breaking down when the Sierra Club began demanding laws that would stop ecologically unsound logging practices on both public and private land.

Large redwoods in the Del Norte State Park, California, 1961. Land for the park was acquired in 1924 through private negotiations between timber companies and the Save the Redwoods League. (FHS3880)

Activists soon took to the courts, using federal environmental laws passed in the 1960s and 1970s, particularly the Endangered Species Act, the National Environmental Policy Act, and their state equivalents to push for reforms. In the 1980s, the Pacific Lumber Company sold land including the Headwaters Forest to the multinational corporation Maxxam, which was more concerned with pleasing stockholders than keeping local loggers employed. Local activists—many of them women—tried to rally local loggers to the cause, arguing that sustainable logging benefited them all. But the demand from Earth First! to cease all logging splintered the movement. Their direct confrontation tactics, and the resulting violence on both sides, drew national attention, and the federal government stepped in to stop the Redwood Wars. In the end, the historian Darren Speece concludes, neither side won.

Speece successfully demonstrates that the history of the protest efforts in defense of this one species in this one location is instructive to historians studying the larger environmental protest movement. It was not as simple as tree huggers (radical environmentalist activists) versus tree cutters (workers and logging companies), nor did national groups based in Washington, D.C., direct environmental efforts—paradigms that have long dominated the historiography. Instead, like the species’ canopy, Speece reveals it is a complex web of storylines: environmental groups often battled one another, women frequently led the efforts, and loggers and environmentalists sometimes combined forces for reform, to name a few. Consequently, Speece’s work on this local battle is an excellent contribution to the larger historiography of the environmental movement.