Forest Fires

Forest fire prevention and suppression were principal responsibilities of the early-day Forest Ranger. They continue to be among his most important jobs today. During the dry, hot days of summer, there is always the feeling of expectancy in the minds of those who carry these responsibilities.

There have been fires in the forests as long as there have been trees to burn. Lightning has always been the cause of most of the fires in the forests. Before the white man, the Indians started fires to clear debris to provide better grazing near their favorite camping areas and to dispose of brush and logs from their trails. There are also accounts of the Indians starting forest fires to repel an enemy attack.

It is difficult to find an area today, even in the best stands of dense timber, that doesn't show evidence of past burns.

As climatic conditions determine burning conditions, some years give more trouble than other. In 1889, the present site of the Spotted Bear Ranger Station and the surrounding area were burned. There were also large fires that year in the Tally Lake District, as well as in Marshall, Shaw, Camp, and Basin Creeks in the upper South Fork. There is evidence of the 1903 burns at the present site of Limestone Cabin, Milk Creek, most of Whitcomb Creek, and nearly all of upper Twin Creek above Nanny Creek, as well as a large area including Hart Basin in the upper Spotted Bear River Country.

The next bad fire year was 1910, generally considered the granddaddy of all fire years for northern Idaho and western Montana. In 1910 millions of acres burned and nearly a hundred lives were lost. Following this unparalleled year of disastrous destruction, the Forest Service began to reorganize to be in better position to meet the challenge of forest fires. More guards were employed, communications were improved, more equipment was made available, and detection procedures improved.

In 1919 approximately 150,000 acres of the present Flathead National Forest burned. Communications and transportation were still big problems at that time. There was a large fire burning in the upper portion of White River on the South Fork. It required two weeks for a pack train to make the round trip from Coram to this fire. Trenches and swaths made to control this fire are still visible. The big fire south of Java that year started from a burning building at Dr. Stanley's sanitarium on Bear Creek. It burned approximately 30,000 acres.

In 1926, the North Fork, Big Prairie, and Tally Lake Districts had large fires. But the largest one was the Lost Johnny fire on the Coram District. This man-caused fire burned from Lost Johnny Creek, west of the present Hungry Horse reservoir, to the Middle Fork of the Flathead River above Nyack.

There were two large fires in 1929. One was the Sullivan Creek fire; it burned 35,000 acres on the Spotted Bear District. I was dispatcher (called commissary clerk in those days) on the Spotted Bear District that year. I had time charged to this fire from August 9, when the fire started, to November 18, when it snowed: a total of 101 consecutive days.

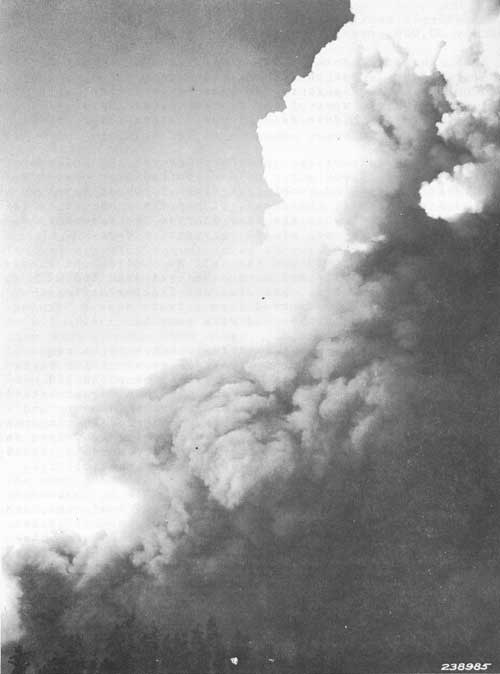

The largest fire in 1929 was the Half Moon fire. It started north of Columbia Falls and burned an estimated 100,000 acres of National Forest, private, and Glacier National Park lands. This fire started from private debris burning. The Swan Valley had another bad fire year in 1934.

Half Moon forest fire, 1929.

Although the Flathead has had no destructive fires since that time, the Forest continues to average about 100 fires annually. The most fires in any one year were the 360 fires of 1940. Improvements in communications, transportation, firefighting tactics, better utilization of manpower, and the use of modern equipment are responsible for keeping many fires small. However, we cannot take anything away from the earlier Forest personnel in regard to their courage, loyalty, and self-sacrifice in carrying out their responsibilities against seemingly insurmountable odds.

The use of airplanes in transporting men and equipment, dropping of retardants and smokejumpers, the use of bulldozers, chainsaws, and other mechanized equipment, along with airplane detection, are also contributing to better firefighting results.

The battle against big forest fires is not over; we will always have them in some areas under certain conditions—for example, the circumstances under which the Sleeping Child fire started on the Bitterroot Forest in 1961. Lightning struck and the fire started around 4 p.m. It was in an area of lodgepole pine windfalls, piled 10 to 15 feet deep with thick reproduction growing up between the logs. It was near the top of a rather flat, round-topped ridge. Burning conditions were very high. The report was radioed to headquarters immediately. Thirty-five men from a fluorite mine with tools and a bulldozer were within a mile of the fire and were dispatched immediately, as were retardant planes from Missoula, less than 50 miles away. The men, bulldozer, and retardant planes were on the fire within an hour but when they arrived, the fire was four acres in size and so hot that control was impossible. This fire burned more than 20,000 acres before it was controlled. Although this fire was an exception, there will be other exceptions in the future.

I think it fitting to relate here an example of present-day action taken on another fire in the Bitterroot Forest. In late August of 1961, a fire was started by lightning just before dark on a round-topped knoll just northwest of where the Sleeping Child fire had started a couple of weeks earlier. The fuel on the ground was almost identical to that of the Sleeping Child fire. It looked to those concerned as though there was to be another big fire.

"By" Amsbaugh, who was in charge of the Sleeping Child fire at the time, radioed the fire desk in Hamilton and gave this message, "I want all the retardant planes Missoula can supply to hit this new fire (Two Bears Mountain) in the morning as early as possible and to keep coming until I tell them to stop." I was on the fire desk in Hamilton at the time and gave this message verbatim to the fire desk in Missoula. It so happened that quite a large number of retardant planes had returned from other fires in Idaho and were standing by in Missoula. At daybreak they all headed for the Two Bears Mountain fire. The planes dropped their loads of chemical fire retardant and returned for more. After about two hours of this, one pilot called me and asked where this fire was. I gave him the information and he said, "That is what I thought. But all I can see now at that location is a mountain that looks like its top is all covered with snow (borate)." About this time "By" Amsbaugh cut in by radio from a helicopter and said to cancel all retardant planes, that the men now on the ground could "mop-up" the fire. Thus, one potentially large fire was prevented.

Due to the difference in burning conditions, this same action could not have stopped the Sleeping Child fire. Both fires were on the Bitterroot Forest but the action would have been the same on any Forest under similar circumstances.

Man-caused fires are of the greatest concern to the Forest Ranger. Man-caused fires usually start at lower elevations. Lightning fires, however, usually start at higher elevations where there is less timber. Also, lightning is usually accompanied by some moisture or higher humidity.

Twenty-five years ago the Flathead Forest manned 147 lookout points during the fire seasons. About this number was maintained for several years. The first reduction came in 1945 when air patrolling was substituted for the Continental Unit which included the Schafer, Big Prairie, and greater portion of the Spotted Bear District. Air patrolling proved to have great advantages over fixed positions and is more economical. At the present time, the Flathead Forest maintains only 21 lookouts. Their primary function is to record lightning storm paths and serve as lookouts at night or at other times when patrol planes are not in the air.