“Forests, Laws, and Peoples’ Rights: Snapshots of Forestry History”

This blog post is the fourth in a five-part series written by Yale School of the Environment students enrolled in a graduate seminar that accompanied the spring 2025 Yale Forest Forum, “A History of People, Forests, and Forestry.” The webinar series and seminar were cohosted by the Yale Forest Forum and the Forest History Society.

Each student was asked to select a presentation and write an essay reflecting on what they learned. Miki Nakano selected Marcus Colchester's "Forests, Laws, and People’s Rights: Snapshots from the History of Forestry." You can watch the presentation video on Vimeo.

***

Today, forests are home to roughly 600 million Indigenous and tribal peoples (Colchester 2025). The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimates that one-third of the global population relies on forest goods and services for their livelihoods, food security, and nutrition (Jin 2025). Since the colonial era, exclusionary, extractive, and capitalist policies have guided forest management practices particularly in the tropics, resulting in the eviction of native populations who called forests home for centuries (Colchester 2025). In his lecture, Marcus Colchester, a senior policy advisor for the Forest Peoples Programme (FPP), explored the history of European-style forestry and how his work with FPP and the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) seeks to restore customary rights for Indigenous peoples around the world (Colchester 2025).

Colchester began his talk with an overview of the history of ancient forests, starting with the formation of forests as hunting reserves for royals in 700 BCE in Assyria. He explained how hunts within royal forests became a means for kings—from Charlemagne to Henry II—to assert their power, masculinity, and impunity. To create the “new forests” in England in the medieval era, thousands of peasants were removed from their homes and forbidden from entering royal hunting reserves. The Forest Charter of 1217, however, required the Crown to give lands to barons to reclaim forests as a source of fuel for the people. Although ownership of forests expanded beyond the royal court, peasants were required to pay to access land. By the 18th century, control of forests was divided between the Crown, landowners, and Parliament. Left out of the agreements were the peasants. Parliament passed strict rules, such as the Black Act in 1723, that permitted the death penalty for peasants who entered forests for poaching.

During the 19th century, forest reserves became the sites of scientific research for strategic state industries and were restricted for popular use across Europe. Colchester referred to this as colonial forestry, and explained how this style of forest management was utilized by colonial governments in Burma, Thailand, and India. Colchester spoke of the ways in which native people were removed from their homes as colonial governments entered into contracts with logging companies that cleared forests for lucrative lumber for international trade, railway sleepers, boat construction, and so on. As Colchester noted, the “logging concession system became rapidly enmeshed in corruption, [and] collusion between the executive and the companies. This has continued since independence, becoming a means of elite enrichment and to pay for party political campaigns for succeeding in democratic elections” (Colchester 2025).

Today, there are numerous state forests that are the direct result of these colonial forestry policies and are reinforced by independent national governments across the tropics (Colchester 2025). The most serious impact of such practices, Colchester argued, is that forest peoples continue to be excluded from the sources of their livelihoods. Securing access to land and customary rights for Indigenous communities has been at the forefront of Colchester’s work with the FPP and FSC. The United Nations Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (UNREDD) Programme defines customary rights to land and resources as “patterns of long-standing community land and resource usage in accordance with Indigenous Peoples’ and local communities’ customary laws, values, customs, and traditions, including seasonal or cyclical use, rather than formal legal title to land and resources issues by the State" (CCBA 2008).

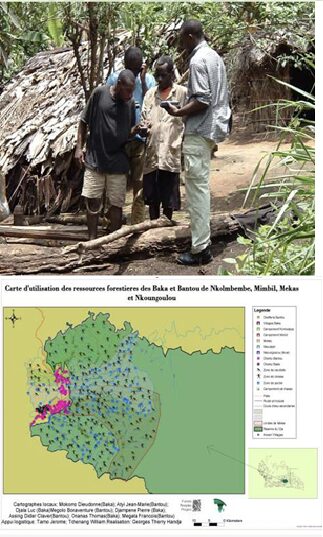

In collaboration with the FSC, Colchester has worked to restore customary rights to indigenous populations who have been removed and restricted from their ancestral homelands in Indonesia and in other parts of the Global South. Colchester and FSC assists communities in mapping their customary rights to indicate the location of sacred sites, historical areas, and how they overlap with other uses that are imposed. He spoke of the remedies offered by FSC for past harms caused by forest conversion, and how they are supporting communities such as the Tobo Batak province of North Sumatra to recover from the destruction of their 2000-year-old frankincense forests (Colchester 2025).

Colchester has dedicated his career to advocating for Indigenous’ communities right to land through policy changes aimed at undoing extractive colonial land-management practices. His lecture reiterated the harms of colonialism as it relates to forest management and emphasized the importance of following through on the promises of international intergovernmental agreements aimed at protecting customary rights around the world.

Works Cited

Colchester, Marcus. “Forests, Laws, and Peoples’ Rights: Snapshots from the History of Forestry.” Yale Forest Forum, New Haven, CT, January 30, 2025.

“Customary Rights.” Appendix B Glossary. Climate, Community & Biodiversity Project Design Standards, Second Edition. December 2008.

Jin, Sooyeon Laura. “Forests and Foods: Nourishing People, Sustaining the Planet.” UN Chronicle. March 21, 2025.