Smokey Bear

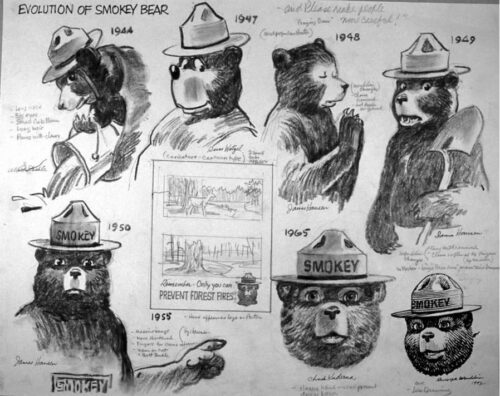

Smokey Bear's appearance has changed over time, and has continue to change since this compilation was created in 1992. (FHS Archives)

The Smokey Bear Wildfire Prevention campaign is the longest-running public service campaign in U.S. history. Since 1944, the iconic symbol has taught millions that they can prevent wildfires. The character was authorized on August 9, 1944, a date now celebrated as Smokey’s “birthday.” Artist Albert Staehle revealed Smokey Bear on October 10 of that year, complete with his trademark campaign hat and jeans. Three years later, Smokey’s slogan—“Remember ... only YOU can prevent forest fires”—made its debut. It proved so effective that within a few decades, just the image of Smokey’s face with the words “Remember” or “Only you” conveyed the message. After more than half a century of warning about the danger of forest fires, in 2001, to reflect the reality that some fire was ecologically beneficial, Smokey’s message was changed to “Only you can prevent wildfires.”

Smokey's origins date to World War II. Wartime demands limited the number of firefighters, leaving communities to deal with wildfires as best they could. Prevention became crucial. To help with this, the U.S. Forest Service organized the Cooperative Forest Fire Prevention (CFFP) program with the National Association of State Foresters and the War Advertising Council (which became the Advertising Council after the war ended). The program’s purpose: to inform the public about how forest fires could undermine the war effort and destroy much-needed lumber. To reach a younger audience, the CFFP chose a bear as its messenger. Its creators were inspired by a heroic New York City fireman named Joseph “Smokey Joe” Martin.

Over the decades, several artists have drawn Smokey. Albert Staehle is credited with drawing the first Smokey image, which looks more realistic than those that followed. Rudolph Wendelin served as Smokey Bear’s official artist from 1946 until his retirement in 1973. He made him look more human and added Smokey’s name to his hat and belt buckle. He also mentored several other artists, ensuring that Smokey would have a consistent look.

Smokey's popularity skyrocketed in the 1950s for three main reasons. Smokey appeared in innumerable children’s books and coloring books published to convey his message. In 1952, children could write Smokey Bear to receive a Junior Ranger kit, complete with a badge shaped like the Forest Service shield but with Smokey’s face embossed on it. During the first three years of the program, 500,000 children became Junior Rangers. Over the next decade, he got his own television special, an animated Saturday morning cartoon series, and a balloon in the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade. Today, Smokey's message is disseminated to young adults through several social media platforms, including Facebook and Snapchat. Messaging is provided in both English and Spanish.

In 1952, singer Eddy Arnold recorded the song “Smokey the Bear.” The song created confusion about his official name: songwriters Steve Nelson and Jack Rollins had added “the” only to keep the song’s rhythm. The same year the song was recorded, increasing commercial interest prompted Congress to remove Smokey’s image from the public domain and require a license to create Smokey products. Fees and royalties collected go into an account for fire prevention education.

In the spring of 1950, a bear cub was rescued from a fire in the Capitan Mountains of New Mexico, treated for his burns, and then transported to Washington, DC, to serve as the living symbol of Smokey Bear at the National Zoo. This bear received so much mail that the U.S. Post Office gave Smokey his own zip code—20252. Upon his death in 1976, he was buried at the Smokey Bear Historical Park in Capitan, New Mexico.

(This information has been adapted from James G. Lewis's article "Smokey Bear: From Idea to Icon," published in Forest History Today in 2018. )

Below are the different materials found in the FHS archival collections, publications, YouTube channel, and blog.

Archival Collections

- Betty Conrad Hite Papers. Conrad Hite worked on both the Smokey and Woodsy Owl campaigns:

Betty Conrad Hite papers - James C. Sorenson Papers. While a U.S. Forest Service employee, Sorenson worked for the Cooperative Forest Fire Program on various Smokey Bear campaigns in Washington, DC, during the 1970s:

James C. Sorenson papers - Rudolph Wendelin Papers. Wendelin worked as the primary Smokey artist from 1946 to 1973:

Rudolph Wendelin Papers

Photo Collections

- Gallery of all Smokey Bear photos in the FHS archives: Smokey photos

- Photos of the rescued cub named "Smokey": The "Real" Smokey Bear

Publications

- Harald Fuller-Bennett and Iris Velez, "Woodsy Owl at 40," Forest History Today (2012). [PDF] How the Smokey Bear campaign led to the creation of the anti-pollution character Woodsy Owl.

- James G. Lewis, “Smokey Bear: From Idea to Icon,” Forest History Today (2018). [PDF] A brief history of Smokey Bear through 2019.

- James G. Lewis, "Smokey, Walk Away from the Walk of Fame!" [BLOG] Some reflections on the effectiveness of the Smokey campaign in advertising circles.

- Jeffrey K. Stine and Ann M. Seeger, "The Material Culture of Environmentalism: Looking for Trees in the Smithsonian's Pinback Button Collection," Forest History Today [PDF]. Page 5 has buttons showing how Smokey has been used as a stand-in for the Forest Service.

- U.S. Forest Service: "Remember — Only You...": 1944-1984 – Forty Years of Preventing Forest Fires – Smokey's 40th Birthday [PDF]. A booklet illustrated with fire prevention posters from 1942 to 1984.

U.S. Forest Service History Reference Collection

- Cooperative Forest Fire Prevention (CFFP) program campaign materials: 1948, 1951, 1952, 1953, 1954, 1955, 1956, 1957, 1958.

- Smokey Bear Press Clippings: No. 2 (1953-1954), No. 5 (May 1955), No. 6 (September 1955), No. 7 (November 1955), No. 10 (June 1957), No. 14 (May 1959), No. 15 [a] (1959), No. 15 [b] (November 1959), No. 16 (February 1960), No. 17 (July 1960), No. 18 (September 1960), No. 19 (December 1960), No. 20 (March 1961), No. 21 (July 1961), No. 22 (October 1961), No. 23 (December 1961), No. 24 (February 1962), No. 26 (September 1962), No. 27 (October 1962), No. 28 (February 1963), No. 29 (April 1963), No. 30 (July 1963), No. 31 (August 1964), No. 32 (July 1965), No. 33 (January 1968), No. 34 (June 1968), No. 35 (November 1968), No. 36 (September 1969).

FHS's YouTube Channel

- The "Fire Prevention and Suppression" playlist includes Smokey Bear public service announcements from the 1970s and 1980s