A River Runs Through Me: Experiencing Thoreau’s Maine Woods

Before I left to join the Thoreau-Wabanaki Journey on May 26, I had planned to write a blog post that would tie together the 150th anniversary of the publication of Henry David Thoreau’s The Maine Woods with George Perkins Marsh’s Man and Nature and the 50th anniversary of the passage of the Wilderness Act. The pièce de résistance would be posting it in time for National Get Outdoors Day on June 14. (As if those weren’t enough signs from Above about what to write, Mark Harvey’s new book on Howard Zahniser, architect of the Wilderness Act, arrived in the office today. It opens with a quote from Thoreau’s “Chesuncook,” the second essay in The Maine Woods.) After all, paddling through wilderness in northern Maine would offer the perfect opportunity for bringing these themes together in one essay.

But when friends ask me to tell them about the canoe trip down the Penobscot River, I find I’m at a loss for words. They are stunned by this. Usually when I start talking of history or recent travels they remind me at some point that they have a plane to catch next week or it’s time to schedule a root canal. But my trip leaves me unable to really describe what I saw and did. And that, perhaps, was the point of the trip. It was for the experience of being in wilderness, not to document it through writing or photographs. Though I tried to do that, I found my enjoyment increased greatly once I stopped trying to interpret or capture it for others or even for myself. To intellectualize or deconstruct wilderness is to miss the point of being there. The reason for being there was to be there—to be present in the moment, to experience it, with all my senses. Thoreau told me why I was there when he wrote in his journal, “The value of any experience is measured, of course, not by the amount of money, but the amount of development we get out of it.” It took a day or so for me to come to this realization. I was initially so focused on documenting the trip that I was limiting my experience. Everything changed with this epiphany.

So, perhaps the question I should answer is, what did I experience?

Quiet. In the wilderness there’s a level of quiet that cannot be found anywhere else but there. We had a couple of days where we heard no mechanical sounds—no cars, no airplanes, no cell phones. No hum of a refrigerator or air conditioner. The quiet would be broken by sounds I now desperately miss: the murmur of rapids or of conversation coming from another boat or tent, the excited shout when someone spotted an eagle soaring above or a muskrat swimming about us, the cursing of the cold in the morning or the mosquitoes in the evening. Yet even the negatives became positives. Is there any greater sound on a cold morning than hearing “Coffee’s ready” or after swatting away bugs while setting up the tent than “Dinner’s ready!”? After returning to what we came to call “uncivilization” and getting in a car, I couldn’t stand to have the radio on and preferred having the window down so I could just hear the wind. (Perhaps “window” should be spelled “wind-oh!” to truly reflect that delightful feeling of hearing the wind rushing by.) We had long stretches on the river where I’d only hear the sound of paddles entering and exiting the water. But, oh, the quiet! I cannot find it in Uncivilization. This is why we have the Wilderness Act, to provide a place to escape to, to protect Civilization from the Uncivilized.

An emptiness that filled my soul. It felt like there were probably fewer people living in northern Maine now than when Thoreau traveled through there some 160 years ago. The area seems devoid of people. When talking with a native Mainer afterward, I described the region as a “big empty.” He immediately understood this as the great compliment I meant it as. So often we hear people say they want to “get away from it all,” when in fact they mean they want to go to a place that is not their home or office. Usually this means to some other building—be it a vacation house or hotel or resort. Whereas in the middle of nowhere, in the Big Empty, I truly was away from it all. Being “inside” meant being in a tent and the “bathroom” had some of the best views imaginable. We spent three nights on islands that only three weeks before had been under water. Initially intending to post to social media during the trip, I quickly realized this was impossible and put my cell phone away, shoving it to the bottom of my bag. I hoped we wouldn’t have connectivity until the last day. It was a little depressing that we had it before then.

Being on the river led me to not only embrace but to understand Thoreau’s exhortation in Walden: “Simplicity, simplicity, simplicity! I say, let your affairs be as two or three, and not a hundred or a thousand; instead of a million count half a dozen, and keep your accounts on your thumb nail.” Time on the water brought about that simplicity; my “affairs” were reduced to three—eat, drink, paddle. Eat everything offered to me whether I like it or not, drink as much water and coffee as possible to stay hydrated, and paddle hard and straight to get where we needed to go. Granted, we were well provisioned, so unlike Thoreau I didn’t worry about getting by on hard bread or the modern equivalent, dehydrated foods, or having to forage. (However, one night we supplemented dinner with ground nuts harvested from around the campsite. Quite the tasty luxury!)

But, simplicity! Why worry about inclement weather or being in wet clothes? These are things I couldn’t control, so why fret or grouse about them? As HDT said of traveling in Maine, “You soon come to disregard rain on such excursions.” One of the most relaxing afternoons was spent sitting under the forest canopy during a thunderstorm that drove us off the river. (Sit and listen to a thunderstorm and tell me it’s not relaxing.) We often quoted Thoreau from A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers: “Cold and damp? Are they not as rich experience as warmth and dryness?” The simpler things became, the happier I became. Emptying my mind of worry filled my soul.

Thoreau is right: Cold and damp is as rich an experience as warm and dry.

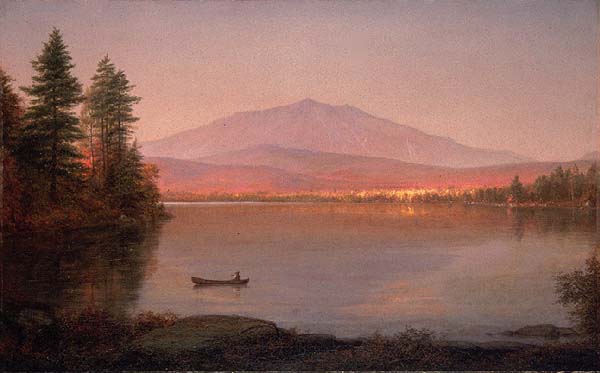

The Hudson River landscape painters were right. I came away from the trip understanding that some Hudson River School painters captured reality in their works. Sanford Gifford, Frederick Church, Albert Bierstadt, and others make great use of light to draw the viewer’s focus to a particular point in a painting. But until now I’d thought what they depicted on canvas could never have occurred in nature, that they were exaggerating the contrasts between light and darks places. I was disabused of this on my first morning in camp.

The view that proved my suppositions all wrong. Though that’s not Mount Katahdin in the background, the effect is the same as in Church’s painting.

“Mount Katahdin from Millinocket Camp” by Frederick Church (1895) (Wikimedia Commons; painting is at the Portland Museum of Art)

And I experienced humbleness. It’s good to be reminded that you can learn a whole lot by opening your eyes, ears, and mind. Like a good way to predict the weather is to actually look at the sky! Whoa. I know, right? Who thinks of that nowadays, what with instant weather apps on their phone? But sure enough, after we spotted a cloud formation called a “mare’s tail,” we had rain within 24 hours, just as the old local saying said we would. Or that the smallest of obstacles—like a single rock in the river lurking just below the surface—can upend a boat. Or that experts are considered experts for a reason. I experienced this time and again with our lead guide, who ensured that 52 people made it through the trip without injury, as well as with the two professors who served as Thoreau experts and with the members of the Penobscot Indian Nation who shared their intimate knowledge of the area and their history with us. I remain in awe of all of them, and stand humbled before them, as I do the landscape they love and shared with the rest of us.

To see an immersive multimedia journal of the trip produced by the Maine Board of Tourism, check out “The Maine Thing Quarterly.” Yankee Magazine sent two photojournalists to document the trip and featured their work in the March 2015 issue. Dreamscapes, Canada’s premier travel and lifestyle magazine, made “Maine’s Untouched Beauty” the cover article of their Fall 2014 issue (click here for a PDF version). The Maine Woods Discovery team organized the trip and their site has more about it, too, including team leader Mike Wilson’s reflections on the trip. After the trip, Canoe and Kayak magazine picked up on the idea and recommended the Penobscot River as a “feature destination.” The article used photos from the trip taken by one of the trip participants Chris Sockalexis. CBS’s “Sunday Morning” visited during the first half of the trip and filed this report on the trip.