Introduction to a History of the Shoshone National Forest

ANNALS of WYOMING

Vol. 4 April, 1927 No. 4

INTRODUCTION TO A HISTORY OF THE SHOSHONE NATIONAL FOREST

Notes and personality sketch by Margaret Hayden,

U. S. Forest Service,

Cody, Wyoming

(The Oldest National Forest in the United States) with Personal Narrative of Its Foundation and Development by the First Supervisor, A. A. Anderson, Artist

Great as is the aesthetic and economic debt of Wyoming and the nation to Mr. Anderson, it is to A. A. Anderson, Artist, we are indebted universally, for he has been many years an outstanding figure not only as a portait painter, but also in recreating out of the great melting pot a truly American art, and ushering in America's golden age of art, a nation's most lasting monument.

The story of Mr. Anderson's artistic life in Paris when it was the art center of the world and his aid to struggling students abroad; the tracing of art from the "Alpine peaks" to the "leavening down" of the present time; and his life today in his New York studios, constitute a chapter to appear in a succeeding number, for the delight and enlightenment of posterity.

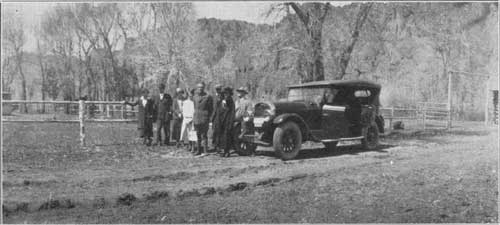

America's First Woman Governor at Oldest Ranger Station in U. S., Wapiti, on Oldest National Forest, Shoshone

Since January, 1922, we have pondered in our heart a paragraph from a letter written by our District Forester, Colonel A. S. Peck:

"Has it ever occurred to you that much of the early history of our Forest areas is in danger of being lost? Mining camps are being abandoned, new roads are being built which change our routes of travel and cause old roads to be abandoned, large stock ranches are being broken up into farms, unique and picturesque characters who have played leading roles in this early development are passing away. Is it not probable that information of this kind would prove of interest in the future and increase in value as time goes on? It seems to me that it is a part of our duty to preserve such data for future generations of foresters."

From the "Outline of History" given in this letter, I have chosen for this number the seventh and last, "Biography of Forest Officers, Human interest stories." Truly Mr. Anderson is both a unique and picturesque character who has played a leading role in early development, not only from an economic but also from an aesthetic standpoint. But for devotion to code, tape, and budget my own pound of spikenard should earlier have been offered, with the hope that its fragrance will last when ledgers are forgotten.

This initial chapter is not submitted primarily as a record of historical facts, but is written as a tribute of esteem (too seldom accorded by a busy, prosaic world) to one who by his lively ideals and undaunted courage was able to combat the selfish primitive interests of that earlier time.

It will be left to succeeding numbers to trace out the romance and adventures of road and trail building, the meeting of motor and pack horse at the end of the trail, the rise and fall of the cattle business, the oncoming of the "woollies," the present day demand for unbroken telephone communication from Wall Street to the Rocky Mountains; and the inception and rapid growth of that other expanding activity now known universally as "dude wrangling." (In official circles the Shoshone is known as the "dude" forest and justifies the appellation. Indeed, it is to our subject we owe the evolution of the genus dude—from pilgrim to "tenderfoot," and in these latter tunes to "dude," "one who washes behind the ears."

But for the activity of Mr. Anderson, our chronicle might measure down to Voltaire's definition of history as "little more than the record of the crimes and misfortunes of mankind." When the first supervisor made his annual trek in the summer of 1926 from the salons of Paris and the studios of New York to his ranch on the Forest, and was besought by us to tell the story of his early triumphs and failures in forestry, he cogently replied, "I had no failures." Whereupon he invited me to visit Palette Ranch, his summer home and hunting lodge in the Rockies. After nine intervening months there is a savor of charm in reliving this experience and soliloquizing, "What is so rare as a week in the forest?"

To go to Shakespeare;—

"A merrier man,

Within the limit of becoming mirth,

I never spent an hour's talk withal;

* * *

So sweet and voluble was his discourse."

Excellent as was the cuisine, I often craved pencil and notebook more than knife and fork, for at our dinners conversation was unhampered and memory unnumbed by thought of an unknown audience.

Exemplifying the true artist's scorn for exotic luxury, breakfasts were served from a red-checkered table cloth, spread in a beaming sunroom. This same table served during the moonlight evenings for bridge games for those who were valiant enough to hazard their reputation at cards with one whose skill had placed him with the world's experts. We have since listened in on model games in the air over Station WEAF, New York, and recognized names of well-known bridge authorities who had been guests of Mr. Anderson at the ranch.

While well-founded reports are reaching us that our hero's latest adventures are along the airplane route, of radio I have nothing to record other than his facetious comment that the broadcasters sounded as though they bad been overcome by ether; with, however, what seemed to be a concession greatly in favor of radio, that his beloved granddaughter, *Betty, is an enthusiastic fan.

*Mrs. H. A. Ashworth, then on a pack trip at their hunting lodge further up the mountains, named by Emerson Hough on a visit there, "The End of the Trail."

Not only is Wyoming particularly indebted to Mr. Anderson for his activity in protecting its woodland heritage, but he has also proved the importance of work as the foundation for all culture, and does not ask others to do what he has not himself done. Many years ago he broke down the tradition that only a woman can cook, when, during his residence in Paris he was taken into the culinary confidence of famous chefs and initiated into the secrets of French cookery. "Anyone may learn anything," said our host, as we relished a dinner he had prepared, "If he has enough energy and curiosity."

Mr. Anderson has also loved to build and to ornament the earth. The story of the building of his ranch home and hunting lodge is a pioneer romance in itself, and is to be another chapter in a succeeding number.

A fountain rising from a palette-shaped plinth played tirelessly at the entrance to the lodge, and nearby a sundial reminded us of the all too quickly passing sunny Wyoming summer, for here at the ranch they live "In feelings, not in figures on the dials." Indeed, already two rough-coated Airedale terriers who constitute part of the yearlong household, seemed to scent preparations for impending departure and their own long winter with the caretaker, for their master declared he thought too much of them to take them to the city.

Perhaps the greatest surprise of all was the nine hole golf course of sportiest hazards, which has been wrested from rocks, roots, and sagebrush. It was good to follow this course with our subject, wishing the while for pencil and paper to take note of the spontaneous expressions and "confessions" that always lend a colorful cast to word pictures. Doubtless it was not so good for "the wearing of the green" that, like other lady novices, we got a good grip on the green by means of our high-heeled boots, thereby proving the patience of our master golfer—a master indeed in the mountains, but who confessed to lower scores at the seaside links. This same privilege was accorded Margo, the pet antelope, as her fleet and slender feet ranged the Palette grounds.

Across the turfy green a swimming pool which had been coaxed from the mountain tops flashed its promise of refreshment plus comfort, for here the artificial had indeed made nature bearable by means of steam pipes which warmed the water from the coolish heights.

To me, the most captivating sport of all, and one at which I considered myself more expert than at golf or bridge, was the horseback jaunt along Piney Creek. Three horses were saddled for us at midday, after another morning's work and noon luncheon, and we were soon across the Forest boundary, on bedgrounds of deer and elk, surveying the range of the largest herd of antelope in the world.

Our goal that day was the old homestead cabin at the source of Piney, which from sentiment had long been preserved, but which our game warden guide had at last decided to destroy, as it had become the rendezvous for poachers on the elk winter range. Already this season there were signs of abuse of neighborly pioneer customs,—a pile of firewood to warm trespassers through another winter of depredations. While deploring the passing of this solid log landmark, we asked permission to christen it. "Never, Never Land."

Crossing Piney we dismounted near the winter quarters of the bear, within sight of the aeries of eagles, along mountain ridges that seemed veritable "holy cities," and had indeed been the subject of more than one of Mr. Anderson's canvases. In a grotto by the hut were fish-like forms, with bubbles for eyes,—algae, we were told, the beginning of things! Certainly a happy haunt this for banshee, pixie, and gnome.

Here as we rested by an aspen grove we heard from Mr. Anderson the legend of the quakin' asp. Tradition has it that the crucifixion cross was formed from the wood of the aspen tree, which accounts for the forever fearful quaking and trembling of its leaves.

Undertaking to keep pace with our agile wrangler-host on the home run over the Forest Service trail, my horse's hoofs scrabbled over a boulder that had defied the ranger's charge of TNT, and I rose from the fall to bear the philosophic comment that to learn how to fall is first in riding.

A whole lot more could be written about Mr. Anderson, but it would have to be done with a subtler quill than I possess; and a far livelier manuscript this would have been with the expressions of sharp wit striking satirical sparks, the neatly turned truisms, and the interlarding of many personal reminiscences. Too frequently I was inhibited by "Don't write that in; I was only telling you about it," and it was with a sense of distinct loss I abstracted many a parenthetical paragraph. But this I could not suppress:

"The closer we get to nature the happier we are. No man can live close to nature and study the wonders of creation without getting nearer to God and loving all His works. We are nearer heaven on the Shoshone than in other places—it is 7650 feet altitude where we are standing—and if we are very quiet we can hear the angels sing."

In a large sunny upper room I had "listened in" and took notes on the prehistoric period of the Forest I love so well, altogether intrigued by this "once-upon-a-time" story of early thought-taking for our precious woodland heritage. Hunting trophies of other days hung from the walls of the lodge, calling forth stories yet to come of the faithful guides who had passed on to other hunting grounds; a cheerful wood fire glowed in the grate below, and I glanced betimes at the horizon of river, forest, and mountain cleft in the foreground by a charred canyon, an ironic monument of what might have been.

MARGARET HAYDEN.

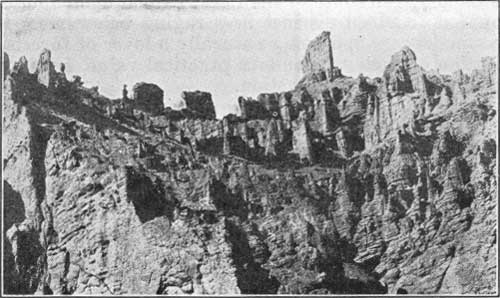

Holy City in Shoshone National Forest, Park County—Courtesy of the State Highway Department.