Essay: Fueling the Fires of Industrialization

Introduction

The United States underwent a period of dramatic change during the first half of the nineteenth century. Previously a predominantly rural nation with many small farms, by the beginning of the Civil War, America had begun a transition towards a more urban and industrial society. Propelled by an influx of European immigrants, in addition to many technological advances, U.S. cities and industry grew at a quick pace. Between 1860 and 1910, the transformation of America into a world industrial power took shape. Historians often call these years of rapid industrialization and urbanization, the American Industrial Revolution. Although sometimes overlooked, wood played an instrumental role in fueling the fires of industrialization in the United States.

Early Forest Products

Even before the United States made its transition to an industrial nation, wood was an essential resource for most Americans. In 1836, lawyer, judge, and writer, James Hall (1793-1868), articulated this point when he stated, “Well may ours be called a wooden country; not merely from the extent of its forests but because in common use wood has been substituted for a number of most necessary and common articles – such as stone, iron, and even leather.” Besides serving as the material used to build most houses through the nineteenth century, wood also was used to construct fences, furniture, roads, bridges, and carriages. Moreover, Americans used wood to cook meals and heat their homes. In fact, by the late 1700s the average American family consumed between 20 and 40 cords of wood each year. In addition to domestic purposes, wood also contributed to the production of iron – a metal of increasing importance to the U.S. economy. Popular because of its plentiful supply and ease in producing fire, wood was used in the smelting of iron throughout the eighteenth and much of the nineteenth centuries. Recent estimates indicate that approximately 5 to 6 million acres of forests were cleared to produce iron during the 1800s.

Wood Begins to Fuel the Industrial Fire

During the latter half of the nineteenth century, use of products from the forest continued to increase. Although coal replaced wood as the major fuel source both in the home and in industry, and brick, iron, and steel were the major components of many machines and buildings of the period, the demand for wood failed to decline. Between 1850 and 1900, the U.S. population tripled from 23 million to 76 million people. Extensive forestland was cleared to make room for the new population and to fuel the increasing industrialization transpiring across the country. For instance, by 1850 over 700 steamboats traversed the American waterways, carrying both goods and people to and from bustling commercial ports. Commonly constructed of wood, steamboats also consumed vast amounts of fuelwood on a daily basis. Steamboats often had to stop twice daily at local “wooding stations” (small, independent operations typically run by squatters, or people with no legal title of ownership to the land they were clearing). Despite coal’s widespread use for fuel during the 1800s, the majority of steamboat operators continued to use wood because of its cheap cost and widespread availability.

Make Way for the American Railroad

Figure 1. Construction ended on the Great Northern Railway's transcontinental railroad on January 6, 1893. Great Northern Railway photo, Forest History Society collection.

Although many changes occurred during America's industrial age, the railroad quickly became the symbol of the nation's rapid progress. In 1847, the noted statesman and lawyer Daniel Webster remarked that the railroad, "towers above all other inventions of this or the preceding age." The railroad altered people's perceptions of time, space, and distance. Whereas traveling by foot or on horse could take days or weeks, railroads oftentimes accomplished the same trip in mere hours. The new mode of transportation facilitated both the dissemination of information and goods; railroads bridged the distance barrier between the different regions of the country helping to forge political, fiscal, and corporate networks. All things considered, railroads not only made traveling easier, but more importantly, tied the growing nation together.

Figure 2. Wooden Crossties (1913). Forest History Society photo.

Consisting of only 3,000 miles in 1840, by 1910, the miles of U.S. railroad tracks leapt to 240,000. Despite earning the nickname “iron road,” railroads utilized a greater amount of wood than any other material and accordingly placed a great strain on American forests. For example, except for the engine and rails, most other components of railway systems such as railroad cars and stations, telegraph poles, bridges, trestles, and fences all were made of wood. Furthermore, crossties, the beams or rods that support the rails, constituted the most significant railroad use of wood. On average, each mile of track required over 2,500 crossties. And, due to deterioration caused by environmental factors like humidity, water, and fungi, wooden crossties had to be replaced every 5 to 7 years on average. By the late 1800s, railroads accounted for between 20 and 25 percent of U.S. timber consumption and led to the clearing of vast amounts of forestland -- in 1900 alone, over 15 million acres of forests were cleared just to replace railroad ties!

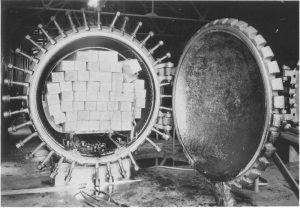

Figure 3. Treatment of wooden crossties (date unknown). Northern Pacific photo, Forest History Society collection.

Many European railroad companies experimented with methods to prolong the life of wooden railroad ties throughout the nineteenth century (due in great part to a timber shortage throughout much of the continent) and similar efforts began in the United States in the 1870s. Most experts agreed that wood was the best material for crossties mainly because of its ability to absorb the impact of fast-moving and heavy trains without breaking. The early ties, typically about 8 inches wide and 6 inches thick, were durable, but also deteriorated quickly when exposed to humidity and moisture.

As the supply of timber nearby railroad tracks began to dwindle into the late nineteenth century, more and more railroad personnel realized the value of implementing techniques to increase the average life of the crosstie. By 1900, 14 small plants oversaw the chemical treatment of wooden crossties. Only four years later, the number of plants increased to 33, a number that rose further still to 102 by 1915. As the price of wood continued to rise amid worries of a timber famine, research studies finding that treating ties with a chemical like creosote could increase the life of the structure, prompted many railroad companies to adopt the practice. Today, most railroads, both in the United States and abroad, still use wooden crossties. Moreover, nearly all modern ties are chemically treated, resulting in an average life of 30 to 40 years, as opposed to a 5 to 7 year life without addition of any preservatives. The technological innovation of chemically treating crossties therefore not only saved railroad companies much money, but also significantly reduced the use of wood for crossties thereby making forests available for other purposes.

More Technological Advancements

Figure 4. Hand-split rails stacked in zigzag fashion were commonplace across early America. Fences such as the one above, consumed large quantities of wood and deteriorated quickly. Forest History Society photo.

Another prime example of how technology helped alleviate the strain placed on American forests during the Industrial Revolution appeared in the treatment of wooden fences. From the colonial period through the mid-nineteenth century, wood was used in the construction of fences. In addition to private farms, fences also appeared around logging camps, railroad tracks, and Western ranches. By 1850, there were approximately 3.2 million miles of wooden fences in the United States, enough to encircle the earth 120 times! Similar to the crossties used in American railroads, wooden fences, when exposed to the elements rotted at a quick pace, and had to be replaced frequently. However, when chemically treated, much like crossties, wooden fences lasted much longer and therefore decreased the number of trees cut on an annual basis for the building of fences.

Besides the treatment of wooden crossties and fences, another technological innovation also alleviated the strain placed on U.S. forests: the invention of barbed wire. Used most frequently by western ranchers and homesteaders, barbed wire fences helped transform the West from a land known for its open spaces, to an area with increasing boundaries and emphasis on private ownership. Although cowboy ballads and songs such as Cole Porter’s, “Don’t Fence Me In,” lamented the loss of freedom in the American West, barbed wire fences proved more effective than their wooden counterparts in preventing the loss of livestock and the open grazing of cattle and sheep. Furthermore, since wood was scarce on American prairies and plains, the use of barbed wire for fences proved much less expensive than wood and in turn helped reduce the strain on eastern forests.

Forest Products: Past and Present

Figure 5. Wooden bats. Photo by R.B. Russell USFS Forest Products Laboratory, Forest History Society photo.

Throughout the history of the United States, Americans have relied upon forest products in many facets of their lives. Colonists used wood to build houses, cook food, and fence in their animals. Early Americans enjoyed consumable goods like cider, maple syrup, and fruits and nuts – all products of trees. A variety of wood was used in the past, and continues even today, as the major components of furniture, such as tables, chairs, bookcases, and cabinets. Additionally, wood, both in the past and present, also occupies an important position in American pastimes. Billiard tables, baseball bats, bowling pins, and jigsaw puzzles, to provide but a few examples, all are made of wood.

In the twenty-first century, Americans continue to rely upon forest products. Through extensive research and technological advances, we now have the knowledge to convert tree fibers, bark, wood components, and residues left behind following the making of paper, into a variety of household products. Cellulose, considered the basic building block of wood, resin, a sticky material found in many trees that hardens when exposed to air, and terpene, a compound derived from the oils of many conifer (cone-bearing) trees and plants, are just three examples of materials extracted from trees to aid in the production of many products. In fact, many commonplace items such as toothpaste, film, vinegar, cutting boards, and carpet all come from trees. In conducting a quick inventory of objects in your classroom or home, you most likely would be surprised regarding the many forest products used in both settings on a daily basis!

Conclusion

America experienced great changes during the nineteenth century. Sparked by technological advances and a large increase in population, the United States evolved into a leading industrial power. Wood played a significant role in America’s transition from a principally agricultural nation to a country of thriving metropolises that manufactured a great variety of goods. The most striking example of the change, the railroad, although called the “iron rail,” relied upon wood to connect the nation. Used to build crossties, bridges, and station houses, in addition to serving as an important source of fuel, wood kept the railroads running by fueling the fires of industrialization. Increased technology and a growing fear of a timber famine sparked advancements (such as the chemical treatment of wooden crossties and fences and the invention of barbed wire) that helped ease the strain placed on forests during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Finally, throughout its history, the United States used many forest products. From furniture to sporting equipment, wood shaped American society and even popular pastimes. Today, forest products often appear in less obvious forms than in times past. As a result of research and development many household items from shampoo to postage stamps are derived from trees.